An American diplomat whom India calls the mother of Hurriyat Conference, was recently in the middle of an espionage drama. But in 1991, this lady diplomat, during a secret meeting, almost convinced JKLF’s top brass to shun gun and embrace diplomacy for a lasting solution. Bilal Handoo recreates what transpired in that meeting and some un-kept promises that shaped Kashmir’s modern history

Pic Courtesy: indialegalonline

Srinagar, Summer, 1991

A senior scribe along with American diplomat has just arrived in Hazratbal – the headquarters of Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF). Donning fatigues, the men with Kalashnikov are everywhere; on rooftops, in alleys, atop fences and inside the shrine. H for Hameed Sheikh and Y for Yasin Malik of JKLF’s HAJY group are behind bars. While as, A for Ashfaq Majeed has lost his life in a grenade blast. Now, J for Javaid Mir is the de-facto commander-in-chief of the militant outfit.

An unsettling calm prevailing over the Hazratbal shrine sporadically breaks with the fluttering of pigeons. Swarms of them are restlessly pecking grains in the lawn. The abandoned police pickets in the vicinity of the shrine are now overtaken by the JKLF men. They stand guard and appear alert. Their probing eyes are scanning the scribe-diplomat duo approaching towards the shrine from Dal Lake side.

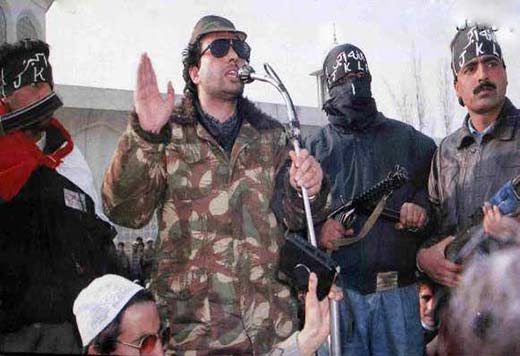

It is yet another simmering summer in valley and the lady diplomat is visibly growing uneasy. They step inside the shrine and sit quietly. Both are now waiting for Javaid Mir for a scheduled meeting. Moments after, Mir – wearing beret, sun glasses and fatigues (with JKLF logo) – walks towards the room. He is being escorted by scores of gunmen. He greets the guests politely.

A few days ago…

A rotary dial telephone is ringing inside the shrine. A JKLF man approaches to attend the call. The caller is the senior scribe from Srinagar who wants to speak to JKLF chief. The man hangs the receiver and runs to call the chief. A few minutes later, Mir walks inside the room and answers the call.

“Look, Mir Sahab, there is this American diplomat I met during my recent visit to New Delhi who wants to have a meeting with you,” the scribe tells Mir.

“Meeting for what?” The JKLF chief asks.

“She is very keen to understand Kashmir’s freedom struggle in detail. She especially wants to understand your point of view. So, what do you say?”

“Meeting is fine,” Mir replies, “but make it sure, she is no sleuth.”

“Not at all, Mir Sahab. You can trust me for that. Her motives appear very much clean. Besides she has an offer for you.”

“Alright, call her in.”

It is because of that telephonic conversation that the scribe and the diplomat are now face-to-face with JKLF chief inside the shrine.

“I hope you didn’t face any inconvenience while visiting here in these times of abnormal vigilance launched by heightened militarization across valley,” Mir enquires.

“Absolutely not,” the diplomat replies.

Mir begins to inform the diplomat about the armed struggle in his usual pumped up address. These days, he frequently delivers such addresses at the shrine, exhorting people to fight for freedom.

In the same tone and tenacity, Mir informs the diplomat about the chequered history of Kashmir. And then he starts talking about the present day grim situation prevailing over valley: killings, disappearances, crackdowns, arson and loot and rapes.

“Basically, we started gun struggle to divert world attention…”

“But,” the diplomat cut him short, “what have you achieved by doing all this?”

“Well,” Mir replies, carefully weighing his words, “we have achieved you!”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, it is the first time any American diplomat has come to hear us out. Is it not our achievement?”

Mir in an attempt to clear smokescreen, elaborates, “before 1988, we were running a peaceful movement for our birthright: freedom. But, nobody took us seriously. Not even America, which otherwise keeps poking her nose in world affairs.”

Students League, Peoples League, Jama’at-e-Islami, Awami Action Committee, Jam’iat-e-Tulba and other bodies were actively seeking the peaceful resolution of Kashmir, he continues, “but instead, we were intimidated, harassed, lodged in jails and tortured. And when all this was happening, nobody bothered to hear us out.”

By recounting possibly each and every bygone detail, Mir has turned the diplomat into a captive audience. “Isn’t America taking active part in resolving world conflicts? Aren’t you intervening in Palestine-Israel conflict? Weren’t your ex-presidents, Nixon, Regal and others keeping close tab on Kashmir situation? America has a big say in United Nations (UN), isn’t it? You see, we presented memorandum at Srinagar’s UN office. But nothing happened. Everyone failed to take a notice to our fundamental right.”

In Jalallabad (Afghanistan), Mir tells her, “I noticed in 1988, how America supported the war against Soviet by supplying every damn thing to Afghanis. If you could support Afghans, why not us, when ours is the oldest conflict of the world?”

The unfolded events since 1947 has frustrated Kashmiris very badly, Mir asserts: “Whenever we raised our voice for the right to self determination we were labelled as Pakistani agents. Government of India failed to recognise our voice. We were pushed to extremes where there was no alternative for us than to pick up guns. And now the same extreme position has compelled you to visit us and hear our part of story. As I said earlier, it is our achievement that American official has finally come to hear us out.”

So here is the thing, the chief tells the diplomat, “let bilateral talks become trilateral by including Kashmiris. We believe such talks are ice-breaking for us to achieve freedom. If you could do that, I promise you as JKLF chief that my militant organisation will switch back to peaceful movement and will support you both politically as well as diplomatically.”

A year ago, then JKLF Chief Yasin Malik was arrested by government forces along with his eleven men at Srinagar’s Barzulla area. Malik’s arrest reportedly made then JK Governor Jagmohan (known for his “peace slip” in Gow Kadal Massacre) to quip, “I have broken JKLF’s neck!” But two days after his statement, the J of HAJY group attacked Srinagar’s Tuttoo ground with rocket launcher, and thereby sent a strong message across that the militant outfit seeking Kashmir’s freedom is still alive in valley. Later when Time Magazine came up with Kashmir story, Javaid Mir featured on its cover page (the only Kashmiri that featured on the front) with heading: “Broken Neck”.

“But you don’t have a political platform to fight your cause politically,” the diplomat tells Mir.

“See, the political platform depends upon the offer. Let Indian authorities recognise our struggle and start trilateral talks with the support of international community, then our political front will be on cards,” Mir replies.

“But see, the irony is: Kashmir is yet to receive footprints of UN peace-keeping forces, otherwise being sent to disputed regions of the world on war-footing,” the JKLF chief continues. “And please note: only 200 killings dismantled Berlin wall. But even after losing thousands, our fate still hangs in uncertainty.”

“Alright, shun the violence and I promise, you will have American support behind your back,” the diplomat assures.

“Look JKLF can deliberate upon that idea, but yes, we can’t enforce that decision on other militant organisations active in Kashmir,” Mir replies.

“But at least, you can break the ice,” the diplomat suggests.

Mir nods in affirmation.

And with that, the two hour long talk ends with a request.

“If you don’t mind,” the diplomat requests, “lets not take photographs as I am on some secret mission! And let’s keep the minutes of this meeting confidential for a time being till some meaningful development will take place.”

“No problem, photographs can wait, but message can’t. I am counting on you. Please spread our message in its true spirit,” Mir hopes.

Before the diplomat leaves, Mir gifts her specially-prepared chochwor (Kashmiri bread) and chrar-e-kanger (fire-pot). “What is this called,” the diplomat enquires about chochwor. “It is called Kashmiri cake,” Mir blurts out before bidding adieu to the visitors.

Fall, 2014

American government indicts its coordinator for non-military assistance to Pakistan for espionage charges. In the line of fire is Robin Lynn Raphel, the same diplomat who visited valley on her “secret mission” 23 years ago and promised Mir an “elusive” American support. Fluent in French, Persian and Urdu, Raphel is a former American diplomat, Ambassador, CIA Analyst and an expert on Pakistan affairs who was carrying on the work of the late Richard Holbrooke (whose AfPak team she joined in 2009).

On November 7, 2014, The Washington Post reported that Raphel was under federal investigation as part of a counterintelligence probe. FBI searched her home in October 2014. Her state department office was also examined and sealed. And subsequently, she was placed on administrative leave.

Raphel began her career as the CIA analyst before taking the assignment of political counsellor at the US embassy in New Delhi in 1991. It was the time when the unresolved Kashmir dispute was threatening war between India and Pakistan. In the same year she visited valley and met the then JKLF chief Javaid Mir. What followed was the engagement among New Delhi, Islamabad and Washington like never before on K-question.

With Bill Clinton at the helm of affairs in US, it appeared America was truly and deeply into Kashmir issue. The motives became clear when in 1993, Clinton appointed Raphel as the first assistant secretary of state for a newly created position within the US state department. The position was created to focus on growing problems in Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. The position would keep close eye on K-issue. Importantly, Raphel’s policy recommendations as Clinton’s assistant secretary of state for South Asia were very important.

By the fall of 1993, Raphel set off a diplomatic explosion when she openly challenged India’s “official position” on Kashmir, saying: America doesn’t recognise Instrument of Accession! She maintained that her remark was a background briefing (the official position of Washington). “We view Kashmir as a disputed territory,” she said. “We do not recognise that instrument of accession as meaning that Kashmir is forever more an integral part of India. And there are many issues at play in that time frame, as we all here know.”

Her statement was read as a serious setback to Indo-US relations. Indian government reacted swiftly with fierce tone, emphasising that the Instrument of Accession couldn’t be contested under international law and that “India’s claim to Kashmir stood cemented by this document of history”. Immediately, a torrent of analysis, commentary and outrage followed that concluded in unison: “Raphel’s remark has taken Indo-US relations back by 20 years to the Nixon era.”

Interestingly, it was for the first time in the annals of US diplomacy that the term “disputed territory” was used for Kashmir. This supposedly made Raphel quick friends in Pakistan. When the slain Pakistani leader Benazir Bhutto was on her first state visit to Washington in April 1995, Kashmir issue was discussed threadbare. Many gave Raphel credit for this. (Notably: Her first husband and Pakistan ambassador, Arnold Lewis Raphel was killed in plane explosion along with Pakistani President Gen Zia-ul-Haq in 1988.)

But Raphel’s outspoken take on Kashmir was making the Indian establishment uneasy. A larger sense that prevailed in New Delhi that time was: This American diplomat is going way out of line by questioning and attempting to alter India’s “territorial integrity” by seeking self-determination for Kashmiris. By challenging what New Delhi terms “a purely domestic matter”, criticism mounted for her to a level where many started calling her “India baiter”. But this hardly bothered her. In fact, she sided with Sikh separatists as well and persuaded Clinton to stand with them in disputes with New Delhi.

Back in Kashmir, the situation triggered by militancy and counter-militancy was the top subject of analysis for think-tanks like the Stimson Center during that period. Kashmir was top priority for Indian and Pakistani diplomats in US. Both were involved in a literal tug-of-war to woo Uncle Sam for getting a favourable statement.

In between, Strobe Talbott (the then deputy secretary of state) visited 7-Race Course with the invitation from White House. It was 1994. President Clinton had invited the then Indian Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao to US. By May that year, Rao was in Washington. Speculations, analysis and statements apart, what followed after Rao’s American visit only diluted Raphel’s position in the State Department. A lull over K-question started prevailing. It seemed that Raphel’s Kashmir pro-activeness faced an internal impediment. And then finally in late June 1997, Raphel left the state department’s south Asia position. Soon she got blurred from public memories.

But her departure from India didn’t rest the speculations and controversies. She attracted limelight for reportedly maintaining close links with JKLF’s Mohammad Yasin Malik and Hurriyat (M) chairman Mirwaiz Umar Farooq. Besides, she is said to be very close to the Kashmiri American activist in US, Ghulam Nabi Fai.

In fact, Indian government officials have maintained over the years (though mostly off-the-record) that Raphel was the brain behind the creation of Hurriyat Conference in Kashmir in 1993. The creation, they believe, made Kashmiris as stakeholders against the Indian position – that Kashmir is a bilateral issue between New Delhi and Islamabad and not trilateral.

“Her links in Kashmir run deep,” this is how Indian officials think about her. “To provide a political face to Kashmiri militancy, she got the Hurriyat together and gave them international legitimacy. Raphel is, no doubt, the godmother of the Hurriyat Conference.”

In spite of Raphel’s ‘firm’ K- stand, the course of events, however, suggest Washington’s waning interest to resolve the oldest conflict of the world. In his book “Diplomatic Channels” (2012), former Indian foreign secretary Kris Srinivasan writes on the similar lines: “The Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) snooped on a telephone conversation of Raphel and confirmed that the US wouldn’t back a draft resolution against India on Kashmir moved by Pakistan at the United Nations, and therefore it would fail to proceed any further.”

However, the foreign policy of current US president Barack Obama has already acknowledged that Kashmir represents “a potential tar pit for American diplomacy”. In fact, Obama’s landslide victory in the presidential election (in 2008) sparked off speculations: “the president-elect may appoint ex-president Bill Clinton as his special envoy on Kashmir.”

But the fact is: the Clinton’s Kashmir affair started and ended with Raphel itself. As US president, Clinton had raised concerns over “human rights violations in Jammu and Kashmir” at a White house function in 1994. But, he no longer brought those up. It is believed, after Indian PM Narisimha Rao visited Washington on President Clinton’s invitation in the spring of 1994, the American interest in Kashmir flipped (though Kashmir did find a mention in Washington’s check-list). A year after, this ‘change in American heart’ appeared obvious. In April 1995, Hillary Clinton was in New Delhi. She left India by paving the way for better Indo-US relations. And soon the K-watchers concluded: “America has put Kashmir on a backburner!”

As a matter of fact, it is believed that repeated American mediation attempts at Kashmir over the years (from Harry Truman to George W Bush) have helped US to leverage its Pakistan ties with India. To advance American interests, US presidents have always tried to pitchfork themselves as peacemakers between India and Pakistan. Truman had greatly ‘distressed’ the then Indian PM Jawaharlal Nehru to an extent to complain: “I am tired of receiving moral advice from the US.” And not in a distant past, Bush “took the credit” for setting up meeting between two estranged neighbouring premiers, Vajpayee and Musharraf, at Agra in 2001. But now, Washington’s interest to intervene in Kashmir has apparently tilted towards New Delhi.

Meanwhile, twenty three years have already passed between summer (1991) and fall (2014), but the “disputed territory” is still unresolved. Amid this stalement, JKLF’s Javaid Mir is still brooding over the “elusive” support he was promised by the indicted diplomat when he was the ‘commander crescendo’. But now, heydays seem over for both Mir and Raphel. Militancy isn’t anymore massive. Political front is very much reality now. But, bilateral issue isn’t becoming trilateral. And, Kashmir continues to be a Gordian knot to untie.

If am not wrong, Mir was a 24 year old in 1991. Raphel must be really looking for an excuse to join a cause against India if she actually based off of her decisions based on the learnt propaganda of an inexperienced youth. Mir on the other hand exemplifies the saying, yesterday’s extremist is today’s moderate.

What this article does not mention is that prior to her posting in India in 1991, she had spent nearly 15 years in Pakistan either as an official or as a wife of a American official stationed there.