Moscow’s role in the UN has remained fundamental to New Delhi’s Kashmir policy. The base for this role was laid when the top Soviet leaders were hosted by Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad in 1955. The meeting marked the beginning of what was later termed Gushtaba diplomacy. This long extract from Dr Debidatta Aurobinda Mahapatra’s book India-Russia Partnership explains Moscow’s pro-India stand during Khrushchev era but its dilution during the Brezhnev era, particularly during his initial years.

The Kashmir issue surfaced in the wake of the independence of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 from the British colonialism. Then, Soviet perception towards the Kashmir issue was non-committal. The Soviet Union (USSR) under Stalin was under the impression that the whole Indian subcontinent was an offshoot of capitalism; hence it had no role to play.

It was the cold war, moulded with ideological rivalry between the power blocs that influenced Soviet policy towards the Kashmir issue. Believing that India, like Pakistan, leaned towards Anglo-American bloc, Stalin maintained equidistance from both the countries. Soviet representative remained absent during voting when the Kashmir question came up for a discussion in the UN Security Council in 1948 in 229th, 230th and 287th meetings. (see Year Book of the United Nations, 1947-1948 pp. 387-399).

USSR’s policy towards the South Asian region witnessed a shift afterwards. The then Pakistani Prime Minister Liaqat Ali Khan was invited by Moscow in 1948 after he expressed his desire to maintain diplomatic relations with USSR. But this evolving relationship was short-lived. Following reason could be ascribed to this short lived relationship. Israel became an independent state in 1948 much to the dislike of Pakistan, but hailed by Moscow. This dislike was reflected in demonstration by thousands of Pakistanis outside the consulate of Moscow in Karachi, which annoyed USSR. As a consequence, USSR called off its proposed participation in the International Economic Conference to be held in Karachi same year.

The later years witnessed dramatic changes in the international political scenario. The US-Pak axis grew to a new height. In 1948, Pakistan offered a base to the US in Gilgit. For USSR, the US presence in the South Asian region was to call its superpower rival near its border, threatening its security. In 1949, Pakistani Prime Minister visited the US, where he was offered military and economic support. The US policy towards Kashmir at that time was favorable to Pakistan and “unsympathetic and even hostile” towards India. (Hemen Roy, How Moscow Sees Kashmir, p 9).

Pakistan joined Baghdad pact in 1955 and SEATO, sponsored by the US, 1954. These steps created grave concern in USSR and India. These developments led to reorientation in their foreign policy, as a result of which both moved closer to each other. India’s leadership of non-aligned movement propelled this reorientation.

These factors were responsible in changing the Soviet approach towards the South Asian region. It took four years for USSR, since the inception of the Kashmir issue, to take any stand on the issue. When the UN Security Council met on January 17, 1952 to discuss the Kashmir issue in its 570th meeting, the Soviet delegate, Jacob Malik, spoke at length on the problem. He said, referring to various plans put forward by London and Washington, that those plans “instead of speaking a real settlement, were aimed at prolonging the dispute and at converting Kashmir into a trust territory of the US and the UK under the pretext of giving it assistance through the United Nations”. (Year Book of the United Nations, pp 232)

In support of his argument, he quoted Pakistan and the US newspapers. On August 9, 1952 Pravda published a Tass report on the proceedings of Indian Parliament and supported the proposal made by CPI members, A K Gopalan and Prof H Mukerjee in their debate on August 7, 1952 to withdraw the Kashmir question from the UN. (Surendra Kumar Gupta, Stalin’s Policy Towards India, 1946 -1953 pp 248-249)

The initial response of India to the Soviet offer of close relationship was lukewarm. The Soviet support to India on Kashmir in the Security Council in 1952 was not taken seriously by Delhi. It seemed that India did not want Kashmir to be a factor in bloc politics between two super powers. The Hindu, attributed somewhat similar reasons to Nehru’s position: ” .. .I understand that this is precisely the sort of development Indian diplomacy had been endeavoring to avoid from the beginning – involvement of the Kashmir dispute in the conflict between the rival power blocs and the propaganda and passions of the cold war”. (The Hindu, January 19, 1952)

India wanted an early settlement of the issue. “Indians fear Malik statement on Kashmir may complicate settlement of the dispute”, New York Times, wrote on January 21, 1952, “general feeling here is that India wants an early settlement of the long-standing issue before the UN and that the manner in which the Soviet delegate delivered his frontal attack against the West has hardly contributed towards that end. It is feared in informed circles the Malik’s speech, although it reflects Indian sentiment, might pose new problems and further complicate the dispute”.

Besides the factor of growing US-Pak axis, India’s spearheading of non-aligned movement attracted the Soviet leadership. India was against any sort of military alliance or any sort of hegemonic action of any state. According to TN Kaul, the former ambassador to USSR, “the essence of non-alignment is independence of non-aligned countries to judge each issue on its merits, without any previous commitment to one side or the other, as it affects the national interest of each non-aligned country, the legitimate interest of other non-aligned countries and the larger interest of peace, security and development throughout the world”. (VD Chopra, Studies in Indo-Soviet Relations, pp 23.)

Moscow regarded non-alignment as an integral component of the competitive struggle between East and West, rather than a disengaged influence on this struggle. (Roy Allison, The Soviet Union and the Strategy of Non-alignment in the Third World, pp 3)

Perhaps the key to India’s conception of nonalignment is not only its refusal to join any military alliance, but also its denial to any foreign power of military or naval bases. It would like to keep superpowers and China out of South Asia and out of the Indian Ocean. Besides these arguments, one thing was obvious; it the non-aligned policy of India that brought both the Soviet Union and India came closer. This earned India the Soviet Union’s support on Kashmir in UN. Later years saw the high level visits, which strengthened relationship between the two countries.

In June 1955, Nehru visited USSR. During the visit, a joint communique was issued, which emphasized on international peace, security of small states. Both the Prime Ministers of India and USSR felt that, “it is essential to dispel fear in all possible ways.

The visit of the Soviet leaders, Khrushchev and Bulganin to India in November-December 1955 laid the foundation of a new era in Indo- Soviet relationship. Besides Delhi, the Soviet leaders visited Calcutta, Madras, Agra, Coimbatore and Srinagar. Crowds greeted them with thunderous applause.

Soviet leaders assured India that though India and the Soviet Union had different political and social structures, they had many common stakes in international politics. Speaking at the banquet held in his honour and Khrushchev by Nehru on November 20, 1955, Bulganin said, ” … the word ‘peace’ was equally sacred for both. This desire for peace brings us closer, unites us and allows to participate more actively in the peaceful settlement of complicated international problems”. He further said, “our relations are based on the well-known five principles. These principles were declared by us together with Nehru in the month of June this year … the Soviet Union will strongly support these principles in its relations with India and with other peace-loving countries which have already proclaimed these principles or who are ready to subscribe these principles”. (The Hindu, November 21, 1955)

Khrushchev assured Indian leadership that USSR would ever come forward to help India at times of difficulties. Speaking at a luncheon given in their honour at the Agra Circuit House by the Governor of Uttar Pradesh, KM Munshi on November 20, 1955, he stressed that “Soviet people were not just fair weather friends of India but their friendship would last forever even when the weather frowns or the storm blows strong”.

“Let it be known to the world”, he added, “that the friendship between the two people would continue to grow even at times of difficulties and crises”. Bulganin echoed the same rhetoric in his reply to the civic address given by Coimbatore Municipal Council on November 27, 1955. He concluded his speech with “long live the great republic of India. Long live the people of India. Long live the friendship between the people of India and the Soviet Union, Hind-Russi Bhai Bhai and Hind-Russia Sahodare.” (The Hindu, November 28, 1955)

The Soviet leaders expressed the support to the Indian stand on the Kashmir issue explicitly during the course of talks and speeches.

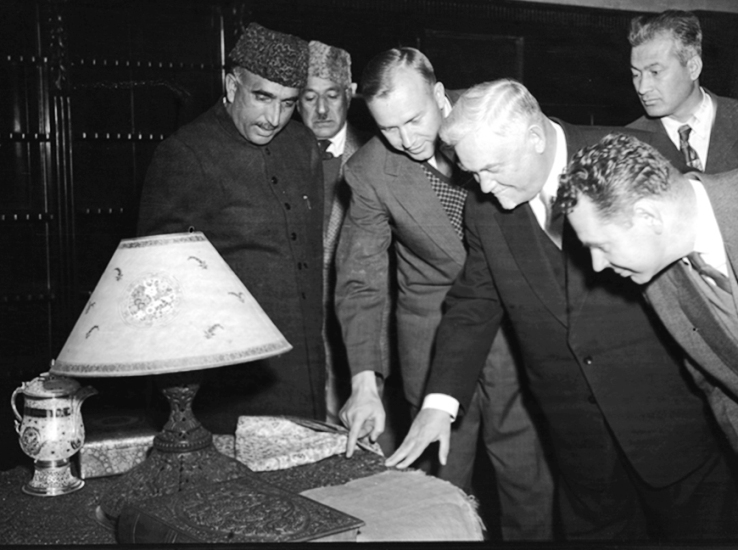

Speaking at the reception given by Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, Prime Minister of Kashmir, in honour of visiting Soviet dignitaries on December 10, 1955, Khrushchev expressed the unequivocal support to the Indian stand on Kashmir. “Kashmir is one of the states of the Republic of India that has been decided by the people of Kashmir,” he said. “It is a question that the people themselves have decided”. He viewed the Kashmir problem as an imperialist design and severely criticized “divide and rule” policy of the imperialist powers. He held the view that the Kashmir problem emerged because some states tried to take advantage of the situation to foment animosity between India and Pakistan- countries recently emancipated from colonial oppression.

They reiterated the same on December 14, 1955 in a press conference in Delhi. Bulganin said, “As for Kashmir during our visit there we saw how greatly the Kshmirians rejoice in their national liberation, regarding their territory as an integral part of lndia”.

On their return to Moscow in the last week of December, they submitted their reports on the visit to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. In his report Bulganin argued that, “on the pretext of supporting Pakistan on the Kashmir question certain countries are trying to entrench themselves in this part of India in order to threaten and exert pressure on areas in the vicinity of Kashmir. The attempt was made to severe Kashmir from India artificially and convert it into a foreign military base.”

But, Bulganin said, the people of Kashmir are emphatically opposed to this imperialist policy. “The issue has been settled by the Kashmiris themselves; they regarded themselves as an integral part of India. We became profoundly convinced of this during our meetings with the people in Srinagar, and in our conversations with the Prime Minister of Kashmir, G M Bakshi, and his colleagues”. Further he said, “The Soviet government supports India’s policy in relations to the Kashmir issue, because it fully accords with the interests of peace in this part of Asia. We declared this when we were in Kashmir; we reaffirmed our declaration at a press conference in Delhi on December 14 and we declare it today”.

Khrushchev in his speech said, “in Kashmir we were convinced that its people regarded its territory as an inalienable part of the Republic of India. This question has been irrevocably decided by the people of Kashmir”

In pursuit of this policy, the Soviet Union opposed the draft resolution co-sponsored by Great Britain, the US, Australia and Cuba on February 14, 1957. The resolution was unacceptable to India. The resolution noted the importance the Security Council “attached to the demilitarization of the state of Jammu and Kashmir preparatory to the holding of a plebiscite”, and “Pakistan’s proposal for the use of a temporary United Nations force in connection with demilitarization”. The Security Council held “that the use of such a force deserved consideration”. (Year Book of the United Nations, 1957 pp 81) The Security Council authorized its president, Gunnar Jarring to visit India and Pakistan to bring about demilitarization or further the settlement of the dispute.

On February 18, 1957 the Soviet delegate, Sobolev, proposed amendments to the above mentioned resolution. He argued “the situation in Kashmir has changed considerably since 1948 when the Security Council had first called for a plebiscite. The people of Kashmir had settled the question themselves and now considered their territory an integral part of India”. (UN Security Council Official Records, 12th session, 768th meeting, February 14, 1957) In his resolution the Soviet delegate deleted reference to “the use of a temporary UN force in connection with demilitarization” in Kashmir. After his amendments were rejected by the other Security Council members on February 20, 1957, Sobolev vetoed the Western-sponsored resolution. He justified the veto by alleging that the resolution, as it stood, favoured Pakistan. (Security Council Official Records, 773rd meeting, February 20, 1957) He told the Security Council that in his government’s opinion the Kashmir question had in fact already been settled by the people of Kashmir.

In March 1959, a Soviet delegation led by A Andrew visited Kashmir to demonstrate that the Soviet Union regarded Kashmir as an Indian state. Shortly after his arrival in Srinagar, Andrew described Kashmir as “the most beautiful place of the world” and reiterated that Soviet Union regarded “Jammu and Kashmir as an Integral part of the Indian Republic”. Pointing out that Kashmir “is not far from the Southern frontier of the Soviet Union” he declared that, “in your struggle we are your comrades”. (Security Council Official Records, 773rd meeting, February 20, 1957, pp 46.)

Next month Indian leader Karan Singh was received by leading Soviet leaders including Khrushchev in Moscow. Khrushchev welcomed the guest from “friendly India” and reiterated the Soviet support to the Indian policy in Kashmir. Karan Singh thanked Soviet leader for his unequivocal support to India and said that the Soviet policy towards Kashmir was well known.

When UN Security Council met on April 27, 1962 to discuss the Kashmir issue, Soviet delegate, Platen Morozov, gave India total and unequivocal support. In his speech Morozov declared, “the question of Kashmir, which is one of the states of the Republic of India and forms an integral part of India, has been decided by the people of Kashmir themselves. The people of Kashmir have decided this matter in accordance with the principle of democracy and in the interest of strengthening relations between the people of this region.”

When the Security Council met again on June 21, 1962, the representative of Ireland, supported by British representative, introduced a resolution. It was quite clear, according to Morozov, the ‘principal aim’ of the draft resolution was holding of plebiscite and this would be nothing but ‘flagrant interference’ in the domestic affairs of India. (Year Book of the United Nations, 1962 pp 130)

Morozov urged the Council to reject the Irish resolution insisting it was basically in line with US dictates. When the Irish resolution was put to vote on June 23, 1962, the Soviet representative vetoed it. He declared that the question of holding plebiscite in Kashmir was ‘dead and outdated’ and the Kashmir question had been solved ‘once for all’.

USSR supported Indian stand on Kashmir at various fora. It also supported Nehru’s decision to withdraw the special status to J&K and to integrate the state into the Indian Union. At a reception at Rumanian embassy in Moscow, Khrushchev declared that the Soviet Union extends its ‘full support’ to the integration of Kashmir to the Indian Republic, insisting his attitude towards Kashmir remains unchanged.

When the Kashmir question came before the Security Council in February 1964, the Soviet representative, Federenko, reiterated his country’s view that the question of Kashmir had already been settled ‘once for all’. He also supported the Indian contention that a Security Council resolution would aggravate the situation and thought that the Indian proposal for a ministerial meeting to discuss the communal question and no-war treaty constituted a ‘realistic approach’ in the interests of peace in Asia and the whole world. (Year Book of The United Nations, 1964 pp 131)

After the unexpected departure of Khrushchev from the Soviet political scene, it appeared that USSR attitude towards Kashmir issue underwent change. However, the Soviet envoy to India, Benediktov assured New Delhi in October 1964 that the Soviet attitude towards Kashmir had remained unchanged. During her visit to Moscow, Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi was assured by the new Soviet Prime Minister Alexi Kosygin that the Soviet support for India’s policy in Kashmir had remained unchanged and that Moscow regarded “Kashmir as an integral part of India”. (Patriot, 24 October 1964)

But the later years were marked with uncertainty regarding Soviet policy towards Kashmir. One of the reasons of this shift could be the Indian defeat in the Sino-India war of 1962.

There appeared to have developed a general trend in Soviet diplomacy to extricate her from an immoderate involvement in intricate problems which were of no direct concern to vital Soviet interests. By adopting such a policy USSR succeeded in disengaging herself from the Indo-Pakistan conflict. It took a neutral attitude towards Kashmir issue, as it was interested to develop closer relationship with both India and Pakistan.

Leonid Brezhnev, unlike his predecessor, decided to adopt a different policy approach towards the Kashmir issue. He envisaged the Kashmir issue as an opportunity to bring India and Pakistan closer and to turn the subcontinent into a peaceful arena under the aegis of USSR. He thought that the Soviet interests could be advanced if India and Pakistan could be developed as an independent counter-force free of American and Chinese influence. If Pakistan could be reconciled with USSR, Brezhnev thought, it would help in improving Indo-Pak relations and would fulfill the Soviet dream of India-Pakistan-Soviet alliance. Such a triangular alliance, if it could be forged, would be a great bulwark against American and Chinese intervention in the subcontinent. (The Hindu October 31, 1964)

Soviet leaders during initial years of Brezhnev period believed that by encouraging Pakistan to establish closer economic and political relations with Moscow, they could easily eliminate the American influence there and at the same time prevent Pakistan from moving closer to China. It was in this context that the Soviet leaders inaugurated their new policy to use Kashmir as a device for furtherance of Soviet foreign policy objectives and invited Pakistan’s President Ayub Khan for a visit to Moscow. On April 3, 1965, Ayub Khan arrived in Moscow and met Brezhnev, Kosygin and other Soviet leaders. Ayub’s visit was concluded with a joint communique containing a formula on national liberation movements, ambiguous enough to be applicable to Kashmir and, indeed, was so interpreted by Pakistan government and its controlled press. (Dawn, April 11, 1965; Pakistan Times, April 12,1965)

From the position of negative neutrality, that is to say, simply limiting the Soviet action to the development of relations with the two rivals, Moscow began to display concern over the manner in which the relations between the two countries continued to deteriorate. Following the outbreak of war between India and Pakistan early in August 1965, Kosygin sent several letters to the leaders of India and Pakistan, appealing for immediate cessation of hostilities and offered his country’s ‘good offices’ in negotiating a peaceful settlement. USSR also came up with a timely warning to all, especially in an indirect reference to the Western countries that: “no government has any right to pour oil in the flames”. (Pravda, September 14, 1965)

At the UN Security Council, where this matter was raised several times, Soviet delegate attempted to maintain a non-partisan view, though he referred to the Indian state of J&K. He blamed the current conflict on those ‘forces which are trying to disunite and set against each other the states that have liberated themselves from the colonial yoke’ and those ‘which are pursuing the criminal policy of dividing peoples so as to achieve their imperialist and expansionist aims’. The friendship with USSR nevertheless stood in good stead when it came to the support of India on points of objection that India raised.

On October 25, 1965, the Indian Foreign Minister, Swaran Singh objected to Pakistan Foreign Minister, ZA Bhutto’s reference to internal situation in Kashmir and held that it was India’s internal affairs. He held that the opposite view was a deviation from the agreed agenda and thus walked out in protest. USSR had shown support to the Indian interpretation that the Council’s deliberations should be only on “questions directly connected with the settlement of the armed conflict, i.e. complete ceasefire and withdrawal of armed personnel. It had also abstained from voting on the resolution adopted by the Council on November 5, 1965. (Year Book of the United Nations, 1965, pp 171) The resolutions failed to resolve the crisis.

On September 17, 1965, in an identical message to Indian Prime Minister, Lal Bahadur Shastri and Pakistan President, Ayub Khan, Soviet Premier Kosygin reiterated the Soviet offer for a meeting in Tashkent to reach an agreement on the restoration of peace. But the Soviet leaders did not put pressure on either side to accept the Soviet peace offer but offered it “if both parties so desire”. USSR was not interested to mediate in the conflict between the two sides but to facilitate to cease hostility and having peace. The Soviet offer of good offices was accepted by both India and Pakistan.

Even during the Tashkent peace process, USSR on many issues came ahead to support the Indian stand. Shastri, addressing a public meeting on December 5, 1965, reiterated his readiness to go to Tashkent and to accept the good offices of the Soviet Prime Minister to bring about understanding and good neighbourly relations with Pakistan. But he made it clear that the question of Kashmir could not be discussed there. (Hindustan Times, December 6, 1965) The Soviet Union had earlier expressed similar view and advised both India and Pakistan to avoid discussing major issues at Tashkent and to regard the meeting as the first of a series of bilateral discussions. (Hindustan Times, December 3, 1965)

Shastri and Ayub agreed to meet at Tashkant on January 4, 1966. At the request of both the parties Kosygin attended the meeting. In his speech at the formal opening of the summit, Kogygin said, “in proposing this meeting, the government of the Soviet Union was guided by feelings of friendship towards the people of Pakistan and India, by a desire to help them to find a way to peace and to prevent sacrifices and hardships brought by the disaster of war”. (Hindustan Times, January 5, 1966)

After a weeklong (January 4-10, 1966) hectic parleys between the two sides, in which Kosygin took active part to break the deadlocks in arriving at a mutually suitable agreement, Shastri and Ayub signed Tashkent Declaration on January 10, 1966.

Kosygin hailed the Tashkent Declaration as “an important political document and ….a new stage in the development of relations between India and Pakistan”. (Hindustan Times, January 11, 1966)

Thus it was the shift in the Soviet foreign policy approach; especially the emphasis on diminishing the US and the Chinese influence in the South Asian region that shaped its policy towards the Kashmir issues.

(This piece is an edited part from one of the chapters of Debidatta Aurobinda Mahapatra’s 2004 thesis Russia And The Kashmir Issue Since 1991: Perception, Attitude and Policy on basis of which he got his PhD from JNU. It was later published as a book India-Russia Partnership (2006) )