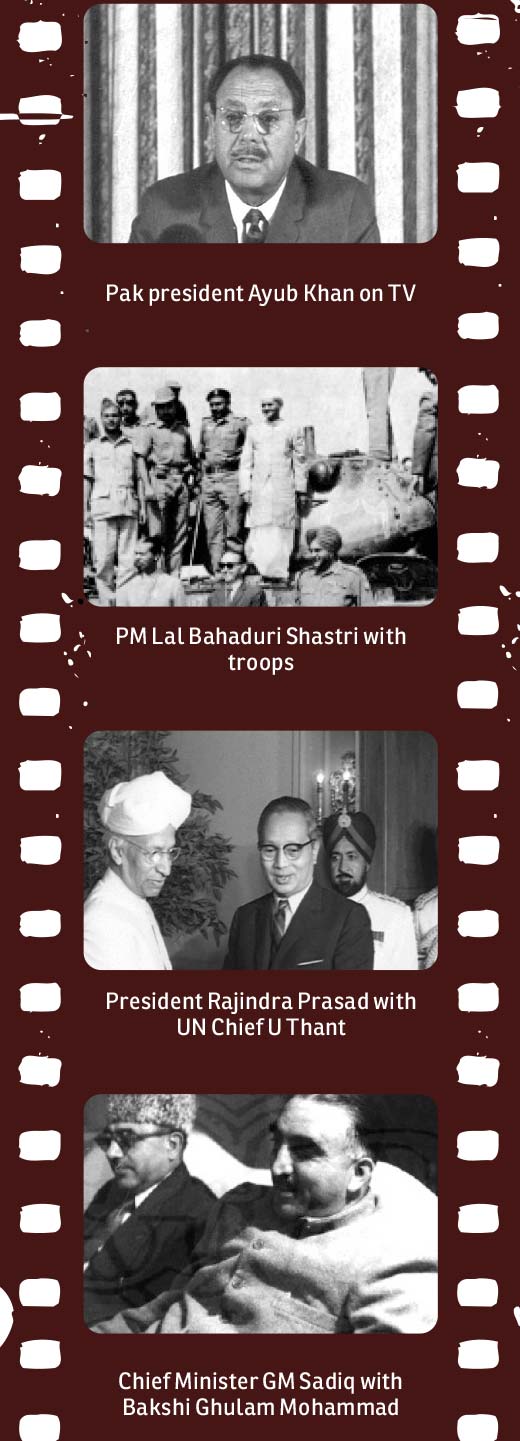

Half a century eclipsed since Pakistani dictator Ayub Khan pushed regulars disguised as Mujahedeen behind enemy lines into Kashmir thinking it would fetch him the Vale and arrest his unpopularity. His coterie’s make-believe plan boomeranged, triggering a full blown war in September 1965 that threatened Lahore. R S Gull revisits the forgotten era that marked death of Kashmir’s student activism, introduced war-destruction, degraded the status of the dispute and changed Kashmir forever by romanticizing violence.

Pakistan’s military historians consumed last 50 years in understanding why Operation Gibraltar happened. Blame game is still on. Diversity of narratives, however, indicates “interesting times” in Delhi, Islamabad and Srinagar.

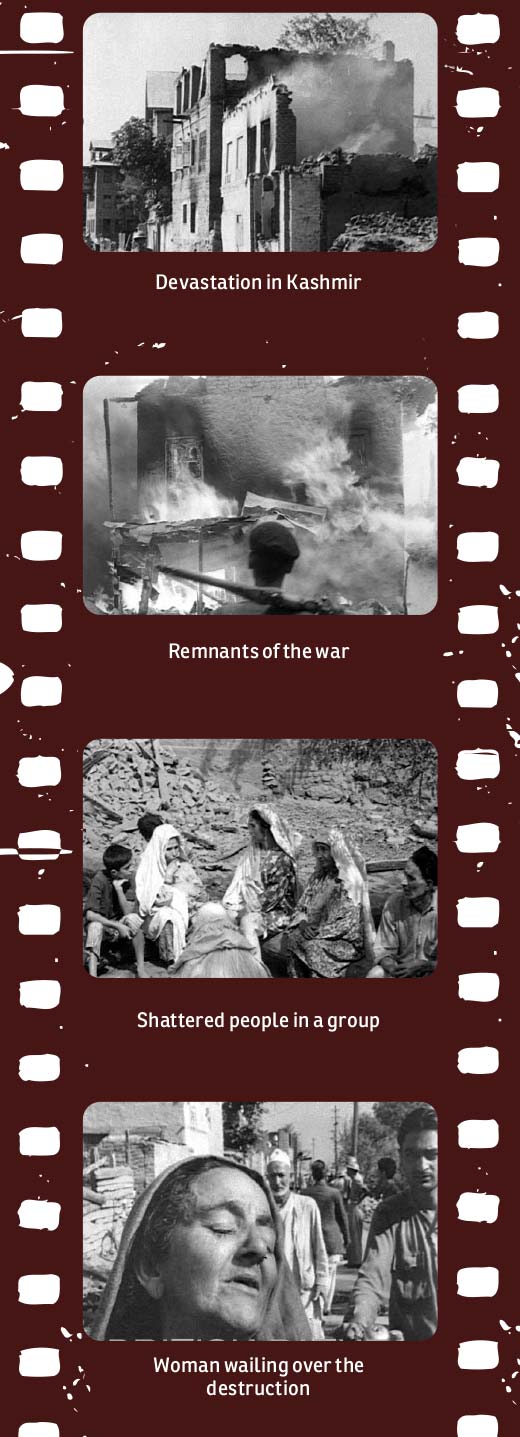

During October 1962 Sino-Indian war, US President John F Kennedy offered military assistance to Delhi and ensured Islamabad stayed away. Seemingly, US wanted using the conflict to bring reconciliation between the two neighbours. Between December 27, 1962 and May 16, 1963 there were six rounds between Foreign Ministers, Swaran Singh and Zulfikar Ali Bhutoo. Initiative proved stillborn.

Srinagar erupted over the mysterious disappearance of holy relic on December 26, 1963. Once it was rediscovered and restored, the agitation diverted to the demand for releasing Sheikh Abdullah. Pandit Nehru who understood the pulse, set Sheikh free and sent him to Islamabad on May 24, 1964 to become a bridge between the two countries. On the fourth day of his visit, Nehru died, forcing Sheikh’s return home.

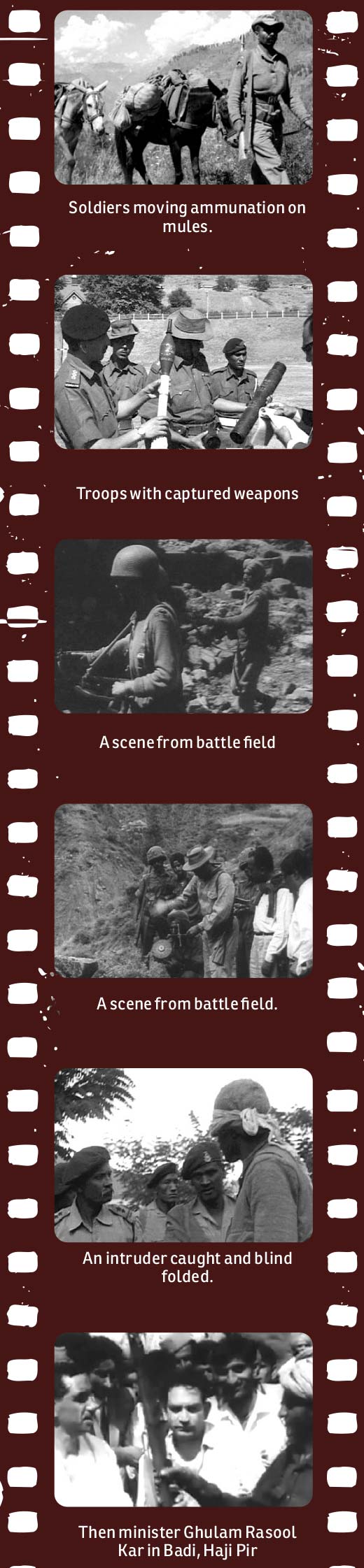

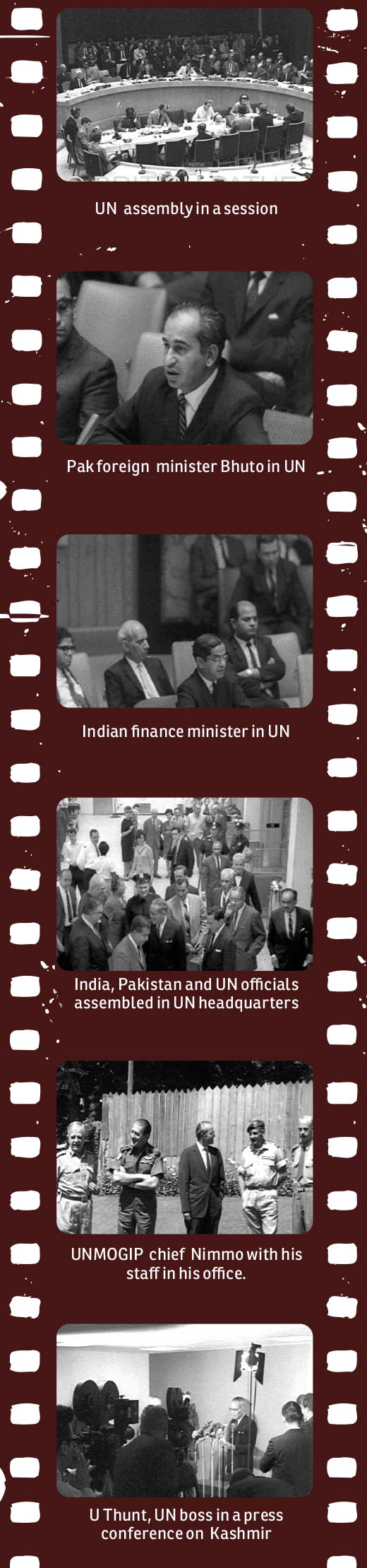

With Lal Bahadur Shastri replacing Nehru, Sheikh was detained (May 1965) after his return from Haj pilgrimage via London and Algiers. Holy Relic agitation ended Bakhshi Ghulam Mohammad’s totalitarian and corrupt regime and, for the first time, people were feeling they can breathe easily. Initially Shamsuddin Kath, his puppet replaced him and later Ghulam Mohammad Sadiq took over in 1965 till 1971. But Bakhshi had initiated certain long term measures well before.

On October 3, 1963, Bakshi announced J&K’s Sadar-i-Riyasat and Prime Minister would now be Governor and the Chief Minister. Six individuals representing J&K in Lok Sabha and nominated by the state legislature would now be directly elected.

Delhi extended Articles 356 and 357 (imposition of governor’s rule by the President and subsequent takeover of legislative authority by the parliament) of Indian Constitution to J&K on December 21, 1964. Soon after, ruling Congress in Delhi announced on January 9, 1965 that it would establish the party in J&K. Seeing deliberate and swift attempts at integrating J&K into India, at the cost of autonomy that was negotiated between 1947, at the time of accession, and 1952, Sheikh’s National Conference (operating under Plebiscite Front then) drummed up protests as Islamabad strongly reacted to the moves.

“Undoing of Bakhshi made Kashmir happy but the pent up anger started coming out,” a top student leader of that era who retired as a senior bureaucrat said on the condition of anonymity. “Chief Minister Sadiq told us he would not stop youth activism as long as it is non-violent, no stone pelting and it encouraged us to the extent that we had a one-mile long procession to UNMOGIP and the then Australian Chief Military Observer General Robert H Nimmo came out and made a speech to us.”

Islamabad, for the first time, was economically better as its currency was valuing more against dollar than the Indian rupee. With US tanks and aircrafts, it was feeling superior to India, especially after being defeated by China. But there were apprehensions that Islamabad may lose its assumed superiority in a few years as Delhi was on a shopping spree.

Icing on the cake was growing unpopularity of Ayub Khan. The last push to his popularity was when his sons kidnapped the daughter of a police officer and he looked the other way. Nawab of Kalabagh resigned in protest. Soon after came his two sons opening fire in Karachi, killing 30 people and then rigging an election to retain power. “Perhaps he felt that by becoming the liberator of Kashmir he would redeem himself in the eyes of the people,” Brigadier Shaukat Qadir, a 1965 war veteran, wrote in his paper The 1965 War-A Comedy of Errors. “… such a venture he hoped to unite the people, for there is little doubt that there has never been greater unity in the country than in the period of the war and immediately after.” He flew to China on March 2, 1965 for three days.

Khan’s discovery Bhuttoo wanted his pie in the cake. Years later, Shabir Choudhary, the UK-based PaK academic-activist with clear anti-Islamabad bias, quoted intellectual Tariq Ali saying in US: “Until these generals are not defeated it is not possible to get in power in Pakistan.”

All this started showing. On April 9, 1965 the rival armies in the Rann of Kutch exchanged fire and it flared up. To reduce Islamabad’s advantage, India made deployments on Punjab border and captured three of Pakistani outposts – Point 13620, Saddle and Black Rocks, in Kargil. With third party mediation, the two sides signed ceasefire agreement on July 1, 1965.

By May, Op Gibraltar was in fast forward mode. The plan envisaged converting 5000 to 10000-strong Gibraltar Force into 10 groups with separate identities and infiltrating them into in ten different areas of J&K: Salahuddin for Srinagar, Ghaznavi (Rajauri), Tariq (Kargil), Babur (Nowshera-Sundarbani), Qasim (Bandipura), Khalid (Qazinag-Naugam), Nusrat (Karnah), Sikandar (Gurez), Khilji (Kel-Minimarg).

Every force controlled by a Major and commanded by Captain rank officer was a mix of Razakaars, “civilian workers” and soldiers from Azad Kashmir Regiment. Attired in green shalwar-kameez, they would carry a cash of Rs 10,000, a lot of ammunition and sneak in. Unlike soldiers, recoded evidence suggests Razakaars joined involuntarily and the process had started soon after the Sino-Indian war.

They have radio sets but, a general belief in Srinagar is, that they would get directions from the public broadcasts that a newly floated radio station Sada-ie-Kashmir would make.

Available military commentary suggests the objectives included provoking Kashmir to rebel, resorting to sabotage, destroying bridges, police stations, barracks and infrastructure thus exposing Delhi’s claim that Kashmir was its part or it was under her control and eventually forcing Delhi to come on negotiating table. These objectives were to be achieved assuming Kashmir will support infiltrators, and India may retaliate in PaK but will never cross international border.

The brutally bold plan faced scathing criticism at home. Soon after being briefed by General Akhtar Hussain Malik, the Commander of Gibraltar Force at Muree, Colonel Syed Ghaffar Mehdi, who headed elite Special Services Group (SSG) termed it childish and bizarre. “…I then asked him, when he expected to launch the Mujahedeen?” Mehdi told in a long revealing interview to Sultan M Hali, a former PAF Group Captain, now a defence analyst. “When he said July, the same year, I nearly choked. I had initially assumed the plan to materialize in a year or two. I told him ‘you will never get away with it’.” Mehdi sent an adverse communication to higher ups against the idea and was eventually replaced by July 30!

“According to (retired) Brigadier Isahaq and Brigadier Salahuddin 98% of the mujahids were forcibly included in the force, and these were the people who had no means to pay bribe to the local police,” Shabir Choudhary, wrote. “Even people from my own village, including some of my relatives, were rounded up and taken to the training camps.”

Two top Kashmir leaders Chaudhry Ghulam Abbas and K H Khurshid had dissociated with the idea.

Operation was not a secret. Mohammad Din, a Gujjar boy from Darra Kassi near Gulmarg, was approached by a group on August 5, 1965 and the official history credits him for the exposure. A quick encounter led to seven killings of infiltrators. Almost same day, Wazir Mohammed of Galuthi (Mendhar) altered army. On August 8, two Captain’s Ghulam Hussain and Mohammed Sajjad were captured near Narian and they gave whatever they knew. Aakashwani broadcast their interviews the same day!

In their joint IDSA (Institute of Defence and Strategic Affairs) paper Operation Gibraltar: An Uprising that Never Was, former top soldiers P K Chakravorty and Gurmeet Kanwal said they were supposed to mingle with crowds celebrating the festival of Pir Dastagir Sahib on August 8, 1965 and joining a political demonstration a day later and taking over the Radio Kashmir, Airport and other vital installations. “Success in these operations would lead to a Revolutionary Council proclaiming itself as the lawful government, which would then broadcast an appeal for recognition and assistance from all countries, especially Pakistan,” the paper reads. “This was to be the signal for the Pakistani Army to move further and consolidate the process.”

Kashmir was not taken by surprise. “Far from rising up in arms, the local population denied any support and, in many instances handed over the infiltrators to Indian troops,” Shaukat Qadir wrote. But Colonel Mansha Khan told historian Justice Yousaf Saraf: “They (infiltrators) could not have come alive if the Valley people had not risked their lives and honour for the Mujahideen.”

A young lieutenant Lehrasab Khan who was part of the action and eventually became Lt Gen, experienced the crisis personally. “The civilian population was also non cooperative because of the fear of Indian retaliation,” Khan told Hali. “Even the logistic supplies reportedly dumped for use by the Gibraltar Force were not available to us. We saw signs where perhaps the dumping had been placed but was either pilfered or removed before we got there.”

“Poor Kashmiris were made the scapegoats. They were never consulted, not even informed that a war of liberation of Kashmir was being started,” Muzaffarabad journalist Mir Abdul Aziz (died February 2002) has told many researchers. He had written on the subject in newspapers too insisting the fighters infiltrated into Kashmir had linguistic barrier. “The whole affair was a wild goose chase.”

“Mujahedeen went to shops and asked for dho seir ata meaning two kilo flour, but they asked in weights which were abolished a long time ago,” Mir observed. “Also the request for atta was enough to expose them that they were not Kashmiris.”

But how far is it correct that the Kashmir leadership of that time was kept ignorant of the happenings.

Khawaja Sanaullah Bhat, the editor of Aftaab was contemporary and a well connected editor. Personally informed by Chief Minister Ghulam Mohammad Sadiq about armed Pakistani intrusion on August 8 – the day Kashmir was on a strike, Bhat in his Kashmir: 1947 Say 1977 Tak has recorded the “mysterious” decision that “leaders of the Movement” took the same evening. Venue for the public meeting at Khanyar on August 9 was shifted to Mujahid Manzil where Moulana Mohammad Sayeed Masoodi advising people to maintain peace and law and order and avoid taking rumours seriously.

“Whatever is happening around you, watch it patiently,” Bhat quotes the political cleric saying. “These are critical times and any small mistake can land you in problems. We are peace loving people, and want to settle our issues peacefully and legally…”

Srinagar was disturbed, panicky and apprehensive. Clashes were taking place in city outskirts and these reached near Bemina. Bhat refers to the August 14, morning meeting between top Army commanders, Chief Minister and his aides, where it was decided that Batamaloo, Sadiq’s ancestral mohalla currently in control of intruders should be set afire, an operation accomplished same evening.

Biggest catch in Bhat’s book lies in his August 18, meeting with Munshi Isaq, two days after latter’s “dramatic” resignation as Plebiscite Front president.

“We have lost the best opportunity to get freedom,” Bhat quotes Munshi telling him ‘almost in confidence’. “Nobody listened to me as everybody in their bid to stay safe, destroyed the entire plan.”

“It had already been decided that we will not stay aloof at this juncture. We had already talked to Pakistan and I had supported their plan….But we (leaders) were frustrated, in a fix and cowards and avoided supporting (to create public opinion),” Munshi tells the journalist. “I saw tears in Munishi’s eyes and the room turned silent, I stayed a bit and then left.”

In his book Nida-ie-Haq, Munshi Ghulam Hassan, Isaq’s son offers a slightly detailed version. The news of the plan was shared by Plebiscite Front’s underground leader Ghulam Mohammad Bhaderwahi to Isaq and to Masoodi. “Sometime later, Rehmatullah, an informer from Pakistan High Commission in Delhi came and had separate meetings with Molvi Masoodi, Molvi Mohammad Farooq and Ghulam Mohuddin Qarra informing them they should arrange a public meeting on August 9 which Mujahedeen will join,” Munshi wrote in his diary, on basis of which his son compiled the book. “He had got some money too and later through his brother-in-law Abdul Jabbar he sent lot of money to Molvi Farooq, Ghulam Mohiuddin Qarra and Mubarak Shah Baramulla…I got to know all this on August 5, 1954.”

Isaq has recorded that a herdsman informed him about the intrusion of hundreds of Mujahedeen on August 5. “I took them to Masoodi and Qarra and they were not surprised,” Isaq wrote. Next day when a Front worker Ahmad Shah Bazaz of Khanqah got one of the intruders with him, Masoodi and Qarra informed him that the local government is aware of the intrusion and army is ready. “Go home or you will be killed,” they advised him. “…These two leaders had alerted the government …On August 9, 1965 Molvi Mohammad Farooq insisted the procession be taken out but the two leaders used their influence and cancelled the procession.” Isaq singled out that while Batamaloo was destroyed, Qarra’s property stayed untouched.

It lacks any reference to its sources but Shabnum Qayoom’s Kashmir Ka Siyasi Inquilab offers a literally damning version of things. Ayub Khan, the book says had sent two army officers Colonel Mushtaq Ahmad and Subaidar Major Sadiq Ali to Srinagar for a meeting with Isaq, Masoodi and Farooq on June 12. “They gave them four lakh rupees and left with a promise of two more,” Qayoom writes. By then intrusion had started and the basic idea was to implement the plan on July 13 itself when 150 armed men were there at the martyr’s graveyard. “At the last moment, Molvi Farooq decided against taking the procession to Amira Kadal.” The same evening there was a fight between the two army officers and the leaders at Mirwaiz Manzil and it was decided that the procession will take place on August 9. “Regardless of everything (allegations of treason), they unwittingly saved Srinagar from a major bloodshed,” Qayoom adds.

Qayoom, however, makes two more sensational disclosures. Firstly, the intruders met a herdsman in Gulmarg and paid him to get 100 Kashmiri caps from Srinagar and that led to the expose. Once it was exposed, the people who were already sheltering the intruders in their homes started throwing them out, some even handed them over to police for rewards.

Secondly, the then Chief Minister Sadiq was personally aware and taken into confidence by Pakistan! “In a private conversation he refused to be part of the plan but he could not deny the fact that two Pakistani army officers stayed at his residence and one of them actually took Professor Zainab of Women College along with him to Muzaffarabad,” writes Qayoom. He says Sadiq would have supported the intruders had they succeeded and even in their failure he helped them save lives and return home.

But alternative accounts exist. “It is incorrect that all the infiltrators were sold and handed over to the police,” Anwar Ashai, the only surviving son of legendary Ghulam Ahmad Ashai said. Then, a final-year engineering student and a top executive of Youth Students League, he was arrested along with scores of local youth. “Their campaign was highly successful in Budgam where they even affected change in the administration and they got massive support in Poonch too.” Ashai says most of the youth was supportive of them.

After engaging the security forces in a series of pitched battles, infiltrators installed a local Sattar Khanday as the Deputy Commission of Budgam with his brother-in-law Ramzan as his Deputy, Ashai said. “I saw one infiltrator in Red-16 and later two more in Central Jail including the one who escaped in a jail break and left with a school teacher whom he married later,” Ashai said. Though a few infiltrators captured were imprisoned in Central Jail, most of them, however, were driven to Jammu where a special lock up was set up in Wazir Villa not far away from Talab Tiloo.

The then Home Minister D P Dhar, Delhi’s most trusted man in Srinagar, was handling the situation.

Ashai said the infiltrators being professionals rarely fell into the trap because they moved in groups but there were instances in which some lost track and landed in police custody. Lot of public property and infrastructure was destroyed but not many figures are available.

Undoing started very soon. By the end of August, Indian army had managed occupying crucial Haji Pir Pass, a crucial bulge on the Gurez divide and key positions in Kargil. These were the main advantages for Pakistan to push in people and manage the control.

Wresting strategic 9000-Haji Pir on August 28, 1965, was a Himalayan success. India failed in its capture in First War on Kashmir. Immediately after its capture, Delhi ensured it is stabilized. The then Works Minister Ghulam Rasool Kar visited the populations in the belt and soon Mrs Indira Gandhi landed and visited the Pass. Traffic resumed on the 46-Kms highway connecting Poonch and Uri.

“I had just passed the matriculation and was appointed as a teacher and my first place of posting was Khawja Bandi (a village on the slopes of the pass) on September 8, 1965,” says Mohammad Hasan Din, an Uri resident who retired as a teacher in 2004. “We were three teachers posted to run the school. I remained there till February 1966 when Tashkent Agreement led to our return. The USSR-brokered agreement enforced status quo ante.

In response to these successes, Pakistan moved army into Jammu’s Chamb sector – the beginning of Operation Grand Slam, the Second War on Kashmir, on September 2, 1965, to capture key Akhnur town. The idea was to block supply lines to Pir Panchal belt and wrest Rajouri where the infiltrators had done phenomenally better than Kashmir. Pakistan delayed the operation by a day (originally planned for September 1) and later at the last moment replaced Major General Malik by Major General Yahya Khan as the commander.

After defending Akhnur, Delhi crossed the IB on September 6, and marched towards Lahore and Sialkote. Western diplomacy got involved massively, stopped ammunition supplies to both and the ceasefire on September 23, 1965 ended the 22 day war. India’s entry into Pakistan marked begining of ex-filtration by Pak intruder for J&K.

It eventually led to eight-day Tashkent summit between Ayub Khan and Shastri on January 10, 1966. Under Chile Brigadier-General Tulio Marambio, UN set up UN India-Pakistan Observation Mission (UNIPOM) to mediate a ceasefire that ceased to exist on March 22, 1966 after status quo ante was restored.

Shastri died in Tashkent. Bhutoo resigned saying “whatever was earned in the battleground was lost on the talks table”.

Costs were enormous: India lost 3000 soldiers and Pakistan slightly more; PAF lost 20 and IAF 60 aircrafts; and the world’s biggest tank battle after World War-II led to Pakistan losing most of its American Paton tanks. In one Punjab village, there were so many tanks left that people called it Paton Nagar. India held three times more territory on the other side than Pakistan occupied on this side.

But legacy of the war still lives. Residents in Tai village, located on the Poonch River in PaK’s Kotli, not far away from the LoC had forgotten their seven soldiers, who went missing on September 6, 1965, and presumed them dead.

In 2006, Ayub Khokar, a JKLF militant from Sarhot village was set free from Jammu jail and repatriated. He went and met Mohammad Bashir, a resident who was barely three when his father Barkat Hussain disappeared. This reopened the wounds and the hunt for getting the detained reached Delhi. By 2011, the families of six Tai residents were fighting a legal battle in the Supreme Court for release of their aged parents who spent more than 46 years in jail!

Khokhar later told BBC he met Barkat and Sakhi Mohammad in Jammu jail in 1998 and they told about four others too. After the court issued a notice, J&K government confirmed their detention and added one more soldier Aziz. In 2012, Delhi informed the court directly that neither of these people were ever arrested in J&K. Nobody knows who was correct. On July 24, Defence Minister Manoj Prabakar informed the parliament that 54 soldiers from 1965 and 1971 wars are still detained in Pakistan!

While military histories suggest the war was no-win-no-defeat, long term consequences of the misadventure reshaped subcontinent. Coinciding with the fall of Dacca in 1971, the Ceasefire Line became Line of Control (LoC), UNMOGIP existed in disuse and Tashkent bilateralism helped Kashmir move out of Security Council, apparently forever.

Contemporaries remember Army scanning villages and collecting the ammunition that fleeing Pakistanis left and it was assumed that Srinagar could have been defended for six months. People supportive of infiltrators were punished. In Pir Panchal belt, where the infiltrators had got immense support owing to their ethnic homogeneity, Zafar Choudhary in his Kashmir Conflict and Muslims of Jammu says “no less than 2000 people were killed” till December 1, 1965 under Operation Clearance.

Operation Gibraltar infused the new romanticism in Kashmir. In UN Bhutoo threatened a “1000 year war on Kashmir”. Ashai remembers two young men from Chenab Valley crossing over and seeking details of some ammunition dumps left untouched. “They were given access to a dump buried near Malangam (Bandipore) far away from the Aka Baji shrine,” Ashai remembers. “And they could only get 12 grenades which various boys lobbed in the city, they all were arrested.” A year later on September 14, 1966 Maqbool Bhat’s group had the first encounter, changing Kashmir forever.

I think India had not opted to attack Lahore if Operation GRAND SALAM had gone as planned by Gen Akhtar Malik without the involvement of Gen Yahya. Because the attack was progressing smoothly and its final phase was to link with GHAZNAVI Force in RAJAURI-BUDIL Region, India would have gone on defensive. GHAZNAVI Force under the dynamic command and leadership of Major Munawar was controlling 500 sq miles of RAJAURI-BUDIL Region (War 1965 by Gen Mahmud Ahmed). Here I append below the comments of a RAJURIAN Kashmiri Immigrant, downloaded from Google. Gen Harbaksh Singh also miserly accepted that they were able to reestablish their administration in RAJAURI-BUDIL Region after the Cease Fire (War Despatcehs 1965). It is also very strange that India awarded Mahavir Chakar to Major Ranjit Singh for capturing Haji Pir about 8 km inside LOC without any resistance by Pakistani Troops where as Major Munawar who captured RAJAURI garrison, Thana Mandi, Naushera and Budil measuring 500 sq miles, butchered 3 Indian Battalions (9 Kamaon, 3 Kamaon, 7 Madras, 2 Artillary Battries and Jhatha of 600 Jain Singh) and kept under administrative control for 2 months was awarded only with SJ.

Comments in response to Indian Gen (Retd) Afsir Karim’s Article “The 1965 War: Lessons yet to be learnt”

1. It seems the Gen was either biased or lacked requisite information regarding the Gibraltar Operation. His version that Gibraltar Operation was a failure is true in substance. All infiltrating forcess less Ghaznavi force could not accomplish their missions due to one reason or the other. But Ghaznavi force completely accomplished its mission. Following facts regarding operations and achievements of Ghaznavi force led by Maj Maliik Munawar Khan Awan have been verified by Pakistani, International press and Indian truth lover analysts.

All raids, ambushes, demolitions and attacks conducted by Ghaznavi force were successful.

It attacked and captured Mehndar, Rajauri (including Rajauri Garrison), Thana Mandi and Budhil. The total area captured was approximately 500 sq miles or 750 sq km which is a record in Military history of Indian and Pakistan Army.

Indian Army launched series of counter attacks but could not regain the lost territory.

India announced head money worth Rs 10,00000 for killing Ghaznavi force Commander “Maj Munawar”. Ghaznavi force kept the captured territory under its control till the implementation of Tashkent Agreement. Maj Munawar established his own administration in Rajauri. Maj Munawar and his force successfully motivated the local population to join hands with them in fighting against Indian Army. A team of UN observers also visited Rajauri while it was under the control of Ghaznavi force after the UN mandated cease fire. In recognition of his achievements Maj Muunawar Khan was awarded Sitar-e-Jurat, Ghazi-e-Kashmir and the title King of Rajauri by Gen Ayub Khan. (In my opinion Maj Munawar should have been awarded with the highest gallantry awards of Nishan-e-Haider by Pakistani Govt and Hilal-e-Kashmir by AK Govt).

2. Above in view with profound regards Gen is requested to correct his record please. He may go through “Twenty Two Fateful Days for India by D.R.Mankekar”, “Operation Gibraltar Total Disaster by Brig Chitranjan Sawant” and InQuizitive (The second Indo-Pakistan war of 1965) by Gautam Basu besides Articals and books of other International, Indian and Pakistani authors/analysts. (Gen it is one of the character traits of brave enemy commanders to accept and admire the achievements of adversaries).

(Abdullah Abdul Wahab Kashmiri)

An immigrant from Rajauri IHK