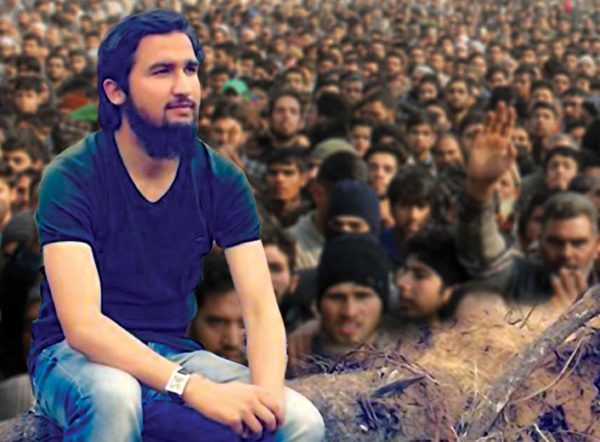

Nobody knew what was going inside his teenager mind, till Basit Dar left and disappeared. For the next 53 days, he was faced with twin parallel chases – one by the police and the other by his parents, one keen to kill him and another desperate to save him. Shams Irfan meets his distraught father to understand the maze of Kashmir’s two parallel universes

On December 14, 2016, Ghulam Rasool Dar, 54, a banker, was ready to begin another day of search, when his phone rang. It was one of his friends from the neighbourhood. “Wait for me. I am coming over,” the neighbour said, trying hard to hide his emotions. “Don’t leave,” he added before hanging up quickly.

Dar, who lives with his four brothers in a spacious three-storey house in Marhama village, 25 kms south of Srinagar, instantly sensed the unsaid, but kept his fingers crossed, hoping for a miracle.

Impatient, Dar walked out of the house, and stood still near the edge of the small verandah. Balancing his tall frame with a pillar, he fixed his sleepless eyes like a question at the front gate – painted steel blue, a colour he hates now.

It was the same gate his youngest son Basit Rasool, 23, an aspiring engineering, walked out of and never returned. It has been 53 days since, thought Dar, while looking at the gate in disgust.

As he stood there, thinking about the day he last saw Basit, his solitary frame resembled the lonely and leafless walnut tree in his spacious courtyard.

Dar recalled how on that day, the courtyard was resonating with giggles, laughter and occasional infant blabber as Basit played with small kids of the dusky locality. A student of the neighbouring Islamic University in Awantipore, Basit was enrolled for the diploma in civil engineering.

Dar also recalled, though like a bad memory now, when he shouted at him: “Just 3 days to exams. You should be studying.”

He could still see Basit, lowering his head, as he would often do when around him, and reply subtly: “I will.”

Before father-son could have exchanged another word, the call for Maghrib prayers echoed through the deserted streets of Marhama.

And with his head still lowered Basit walked out of the blue gate and vanished.

***

Two hours later when Basit didn’t come back, Dar started asking around; first casually; then as another hour passed, his expressions tensed, showing a hint of anxiety on his face.

“Did you see Basit?” he asked one of his friends who was lingering about in an alley near the mosque.

“No,” he replied in a casual tone and asked, “Why? Is something wrong?”

Without answering him, Dar moved on towards the main market, which was shut, but would remain filled with youngsters who wanted to kill time.

As Dar moved from one youngster to another, enquiring about his son, he began to shiver, as weird thoughts filled his mind.

Simultaneously, Dar tried Basit’s phone, only to hear an automated voice telling him that the cellphone he is trying to reach is switched off. Then Dar called his brothers, one by one, asking them if they had seen Basit. “Nobody had any clue,” recalls Dar.

Once home, with hope, assurance, and even promises, Dar broke the news to his wife, two daughters, and his eldest son about Basit’s disappearance.

The rest of the night Dar spent in absolute silence, blaming himself for not stopping Basit, or at least hug him once before he walked out.

***

Next five days Dar spent visiting every single friend he could remember Basit ever had, but without any success. He met all those people who had seen Basit walk out of the mosque that evening. “I had never felt so helpless in my entire life,” said Dar. “I just wanted my son back.”

In first few days Dar realized how little he knew about his son. The following days helped Dar understand Basit, something he confessed, he never bothered to do, when his son was around.

Dar was told how Burhan’s killing on July 8, left an indelible mark on his son’s young and inquisitive mind. He was told how Basit risked his life to participate in Burhan’s funeral in Tral on July 9.

Dar now knew, what he thought was throat allergy, was actually outcome of excessive sloganeering and crying at Burhan’s funeral.

“He came back a changed person from Burhan’s funeral. But I failed to see it,” rues Dar.

The events following Burhan’s killing pained Basit the most. The news of every killing would pierce his fragile soul, but he never showed it on his face.

Dar was told how his son had cried for a week when Shahnawaz Ahmad Khatana, 24, a Gujjar boy, from nearby Dadoo village, jumped into River Jhelum when he was allegedly chased by policemen near Sangam on August 24. Khatana’s dead body was retrieved the next day.

Dar spent many sleepless nights trying to recall the events following Khatana’s death, but couldn’t remember his son’s reaction. It kept eluding his otherwise sharp memory. All he could recall was how Basit would sit with his head down when around him. They would rarely talk about anything other than about his studies, his future and the career.

“I regret every single moment I had wasted talking about future and all. I never tried to understand him as a youngster living in a conflict zone,” said Dar.

***

On the fifth day of Basit’s disappearance Dar got a call from Sangam police station. “Where is your son,” asked the officer in an authoritative tone.

“He is missing since October 21,” Dar replied in a matter of fact manner.

After a brief pause the officer told Dar, ‘we fear your son has joined militancy’.

Then the officer called Dar for profiling of his son, his close friends and family; first at the local police station then by a group of DySps at Cargo, Srinagar.

After the call, Dar instantly shifted his focus of search to areas known for hosting militants, especially from local Hizb-ul-Mujahideen outfit. “I went to Shopian, Tral, Islamabad, Pulwama and many other places,” recalls Dar.

When visiting these locations proved futile, Dar thought of a new plan; a plan he was hopeful would help him find his son.

“I visited families of active militants hoping for a clue. But they were equally clueless about their sons.”

After the visit to Cargo, Dar knew the countdown has begun, and he had to act fast.

With a bit of delay, Basit’s rebellion surprised both sides – the family and the counter-insurgency grid. The news came first to police and then to the father. Nobody knew the reasons, off hand. But both were after him, for absolutely different reasons.

“They were hunting to kill him, and I as a father was searching to save him.”

Dar knew his odds, as he was pitched against a mighty force, well connected network of spies, modern snooping gadgets, drones with powerful cameras, and sophisticated weaponry. “I had just a hope that Allah was on my side,” said Dar.

***

On the fifteenth day when one of Dar’s friends told him that he spotted Basit in Waghom village, just 2 kms from home, it instantly raised hope. Basit seemed within the reach now. “At least now we knew which part to scan,” said Dar.

Unlike in 1990s, the amorphous years of militancy, when men with guns were a common sight in rural areas, Dar realized, finding them now was next to impossible. “The dynamics have changed entirely,” feels Dar.

Dar also realized that the new generation of home trained militants would move from one spot to another, constantly changing their hideouts, trying to stay off the grid.

“Nobody knows who is hiding whom nowadays,” said Dar. “It is like a maze. Only those familiar can go in and out at will.”

Next few days Dar and his brother, his friends, his relatives and every other able bodied soul from distant relations began scanning villages around Waghom.

Every evening they would come back home, assemble inside the spacious courtyard, under the walnut tree, and plan their next move, while giving each other hope that they will bring Basit home soon. “Basit did come, but not with us,” said Dar.

All those days, without letting anybody know, Dar would try his son’s phone, which he had taken along, at least once before going to bed, hoping to hear his voice. But it was always the same lifeless automated voice greeting a pained father.

The more Dar searched for his son, the clearer it became that he knew nothing about him.

“It felt like we were two strangers living under the same roof,” said Dar. “It was a universe parallel to where I lived but hidden, unreal and distant.”

Every night Dar wished he would have talked to him more often. Listened to him, acted like a friend, shared his concerns and joys, and listened to his stories from college and university. But he did nothing. Instead, Dar let a wall build between them, thinking it will help his son become strong and independent.

“I was so wrong. I never bothered to see beyond his silence,” said Dar.

***

As Dar stood near the verandah, with his gaze fixed on the gate, waiting for his neighbour, his brother walked in instead. He had his face hung between his shoulders as he reached near Dar.

Before he could say a word Dar asked him, “Is he coming home then?”

“Yes he is.”

“Then let’s make arrangements,” said Dar before he broke down.

***

At 6:30 am same day Basit and another local militant Masood, who were hiding in an apple orchard in Bewoora village, 5 kms from his home, were encircled by army and police.

After firing a few shots Basit and Masood ran towards opposite directions, trying to break the cordon.

While Masood was successful in finding a “safe spot” outside the cordon, Basit couldn’t get out.

As firing intensified, Basit climbed an apple tree, and raised slogans, his voice echoing through the morning mist. He would fire a few shots and then shout slogans, which Masood responded. Then the entire Bewoora village joined in. After fifteen minutes the sloganeering stopped, and everybody knew why. “Basit was gone,” said Dar trying hard to control his tears.

After the cordon was lifted, thousands rushed to the spot of the encounter. Within no time Bewoora was flooded with mourners.

Some youngsters ringed the spot where Basit had fallen; the soil drenched in his blood and part of his brain was buried in local cemetery with full respect. “Perhaps he is the only militant who has two graves, one in Marhama and another in Bewoora,” said Dar.

***

The wait to meet his son prolonged as thousands of mourners carried Basit’s body to Eidgah, for funeral. “There were five back-to-back funerals,” said a family friend who wished not to be named.

Finally at 2:30 pm, after playing hide-and-seek with his father and family, Basit was home.

To make way for thousands of mourners who accompanied Basit, the blue gate was thrown open.

***

A few days after the funeral, Dar visited Bewoora village where his son died fighting. “As people came to know who I am, they rushed from their houses and circled me,” recalls Dar. “They wanted to meet Basit’s father, not Dar.”

Dar was told how his son remained calm in the face of certain death. “I don’t know, but they (militants) see something that a normal person fails to see,” feels Dar.

For next few weeks Dar’s house was visited by people from as far as Kishtwar, Banihal, Shopian, Baramulla and many other places.

“I don’t know who they were, or how did they knew my son,” Dar said. “But they seemed really pained by his death.”

Almost four weeks later, as mourners still knock at his door, around five dozen a day, Dar regrets just one thing: “I looked for him everywhere and he was literally in my backyard.”

As winter sun sets behind a set of newly constructed houses, an eerie silence fills once bustling courtyard of Basit’s house; leaving Dar with hundreds of unanswered questions, a few regrets, and a void of 53 days.