Mirwaiz Umar Farooq led Awami Action Committee (AAC) was barred from celebrating its Golden Jubilee last month. The party that has remained part of Kashmir’s political life for last 50 years was the byproduct of the agitation over the mysterious disappearance of a holy relic from Hazratbal shrine. R S Gull revisits the half-a-century old reportage to recreate a chronology detailing one of Kashmir’s worst post-partition crises

Those were the most tumultuous years of Kashmir’s politics. His erstwhile Deputy, Bakhshi Ghulam Mohammad replaced Sheikh Abdullah within hours after he was arrested and booked for the infamous Kashmir Conspiracy Case. After a decade of misrule, corruption and hooliganism, Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru finally sent Bakhshi home under Kamaraj Plan on October 4, 1963.

But he picked the then Speaker Shamsuddin Kath as his successor. This helped the ‘iron-fisted’ premiere of Kashmir retain power even after presiding over an authoritarian rule. Sheikh was still in jail. While pro-Bakhshi faction had “hijacked” NC, the Sheikh’s NC was Plebiscite Front.

In this situation, the revered holy relic went missing from Hazratbal shrine. It threw life haywire and created a crisis that even Delhi started shivering. Archival reportage of that era from Indian media is by and large disappointing as it reveals only to the extent that officials permitted. This might have been the outcome of censorship that was in vogue. The reportage from the Pakistani press sounded more exaggerated. Most of the Indian reportage surrounded around a conspiracy that Pakistan fomented but it lacked adequate evidence.

Consequences for Kashmir apart, the relic disappearance triggered massive rioting in West Bengal and East Pakistan (later Bangladesh) that might have left around 400 people dead. Here follows the chronology collated from different newspapers that were published from Delhi, Punjab, Karachi, Dacca and London.

December 27, 1963

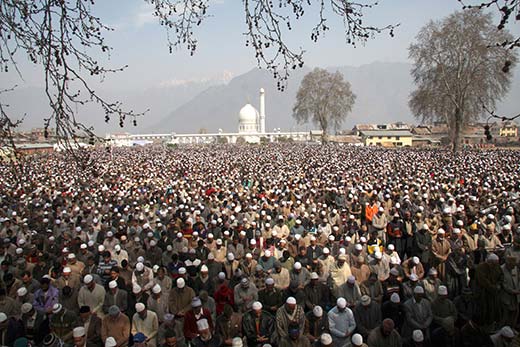

Intense searches coincided Kashmir getting into mourning after the holy relic – a hair from the prophet’s beard, was reported missing from sanctum sanctorum of Hazratbal shrine. Nearly 50,000 people carrying black flags were reported mourning in the shrine. Bakhshi was in Delhi and Prime Minister Shamsuddin in Jammu. The latter started by road but was stuck near Batote.

SP Sheikh Mohammad Aslam told The Times of India that theft was noticed between 2 and 3 AM when one of the two custodians (brothers Hissamuddin and Nooruddin Banday) on duty had gone out for a while. Thieves, he said, had used an iron blade to break the double lock. They had left every other valuable untouched. A British newspaper reported the relic, a “single hair was kept attached to a silver pendulum in a glass tube one inch in diameter with a silver top. The tube was preserved in a silver casket and locked in a cupboard which was guarded by a Moslem family.”

December 28, 1963

Prime Minister Shamsuddin reached Srinagar, visited the shrine and announced Rs one lakh cash reward for any information besides a yearly pension of Rs 500 for the whole of his life. On his request Home Minister Gulzari Lal Nanda deputed two top officers from Central Bureau of Investigations (now IB).

Ghulam Mohiuddin Karra, the leader of Political Conference (then a pro-Pakistan party) had called for a public meeting in Lal Chowk and nearly 100 thousand people assembled. Karra and Mirwaiz Molvi Farooq addressed the gathering.

The situation turned instantly bad as Bakhshi Rashid, MP and NC secretary general and also a cousin of Bakhshi Ghulam Mohammad made an effort to address the crowd. He survived injured as mobs set afire his vehicle and later destroyed two cinema halls, Kothibagh Police station, and two firefighting vehicles. Deputy Commissioner Noor Mohammad imposed curfew restrictions, requested army to help in firefighting. One person was reported injured and two persons were arrested for vandalism. Reinforcement was out to guard the critical infrastructure.

December 29, 1963

It is now known that two persons including a non-local Hindu were killed in the police firing. Officials told Indian Express that they had to fire in self-defence because mobs intended to burn SP in a building and that they wanted the destruction of Radio Kashmir Srinagar. Mourners took one of the dead, draped him in a green shroud and moved around the city for most of the day. While every newspaper reports the details of the shroud, there is no mention of the identity of the dead who was in it!

Around 75000 mourners report at the shrine. Authorities impose a curfew for the next 14 hours. Police arrests Karra, Sheikh Abdullah’s cousin Sheikh Rashid and Congress leader Mohammad Shafi Qureshi.

December 30, 1963

To manage the explosive situation, everybody is involved. Sader-i-Riyasat Karan Singh meets Nehru and Nanda in Delhi. Nehru writes detailed letters to Bakhshi and his surrogate Shamsuddin dubbed as Chamchuddin by locals. Part of the concern is triggered by the adverse coverage that Pakistani media is giving to the issue. Narayan Swami of Indian Express reports from Karachi that Pakistani reaction to the Kashmir incidents is “grotesquely disproportionate” and comments are “more vehement and intemperate than usual”.

Mourning continues everywhere with Hazratbal as the epicentre. Flanked by Akali leader Sardar Aaya Singh Baghi, Farooq Abdullah reaches Lal Chowk and makes a speech, asking people to stay peaceful. Minister Kaushak Bakula leads a mass prayer for a speedy recovery in Leh.

December 31, 1963

Nehru dispatches CBI boss B N Mullick to Srinagar. After interacting with the DIG Ghulam Sadiq, he says the probe is heading in the right direction. Soon after Shamsuddin says “some progress has been made in tracing the culprits”. Later in the evening, Nehru makes a public broadcast sharing the pain of Kashmir, reassuring them and suggesting that “to catch the culprit it is necessary to maintain peace and calm as a disturbance will only help him to get away”.

Shamsuddin alleged that certain political elements and opportunists had made attempts to give a political colour and direction to the crisis. Censorship is imposed on the news, even for non-local media.

Karachi observes black day as Kashmir’s living there take out a massive procession that conclude at Jinnah’s mausoleum. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto issues a statement alleging there are organized attacks on Muslims in Kashmir.

January 1, 1964

Protests have a multi-faith combination as Hindu and Sikhs join in. Scores of roadside voluntary stalls sprung up to offer food to the mourners. A formal Awami Action Committee is set up under the leadership of 19 years old Mirwaiz Molvi Farooq. Security set up works so swiftly that visiting the wife of a Pakistani soldier travelling from Srinagar is intercepted at Jammu. She is questioned, searched and then permitted to go.

In Pakistan Ayub Khan in a radio broadcast asserts Pakistan’s determination to secure J&K people’s right to choose the country they wish to join. In Delhi, Congress leaders say that given the statements issued by Pakistani politicians, it seems as if they have stolen the relic for political reasons.

January 2, 1964

Molvi Farooq and Mohammad Syed Masoodi spoke to gathering and later meet Shamsuddin and B N Mulick. The Times of India reports a Khanyar gathering where there were “more green flags than black” and that people were seeking Sheikh Abdullah’s release. West Pakistan assembly adopted a resolution conveying its deep despair over the theft of holy relic.

January 3, 1964

Home Secretary V Vishwanathan landed in Srinagar to oversee investigations. Home Minister cancels his Bhubaneswar visit as there is no breakthrough. Mourners start walking in funeral shrouds, intercept employees and prevent them from going to offices. The 11-member AAC busies itself between talking to people and meeting officials. Mirwaiz threatens to raise Fidayeen-e-Islam to mobilize the periphery and suburbs, appeals for donations to the central committee.

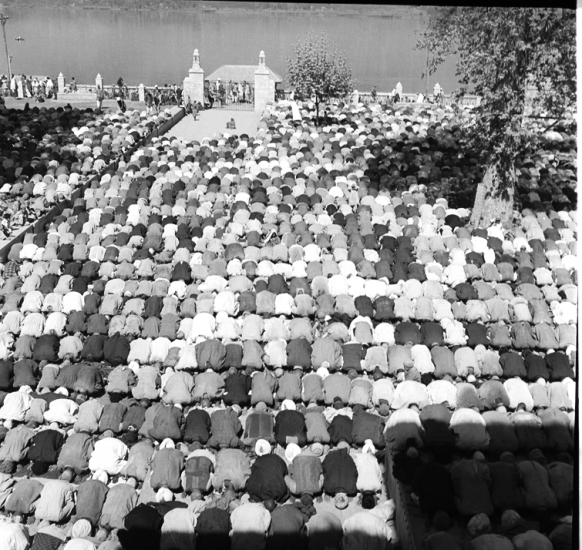

Entire Pakistan is out on roads after the Friday prayers. Jamat-e-Islami founder Moulana Moudoudi also issues a statement toeing the official line.

January 4, 1964

Karan Singh visits Hazratbal, donates Rs 6000 for feeding the poor. He also gave Rs 1000 each to 11 shrines in Srinagar including seven Muslim, one Sikh and three Hindu shrines seeking special prayers for recovery of the holy relic on his behalf.

In the afternoon, Radio Kashmir Srinagar interrupts the routine broadcast to accommodate Shamsuddin. “Today is indeed Eid for us,” an excited Kashmir premier says. “I am greatly relieved and happy to learn that the holy relic has been recovered. I send my hearty congratulations to you and to the people of Kashmir.”

It changes the street mood. “Women threw off their veils and men tossed their caps and turbans in the air in unprecedented scenes of merrymaking after receiving reports the relic was recovered,” Indian Express reported. Mourners turn jubilant and the mikes are used to praise the CBI boss. But a new situation emerges. People want the identification of the culprits and confirming the authenticity and genuineness of the relic.

Within hours after the recovery, AACs Molvi Masoodi meets B N Mullick. He has four demands: 1. Restore the relic to the shrine, 2. Identify it through a mutually agreed group having an intimate knowledge of it, 3. The release of all detainees and 4. Dissociate state police from the investigations of the case.

January 5, 1964

Home Secretary Vishwanathan tells media that the relic was surreptitiously put back in its original place. Asserting that it is genuine, he said it was in its original container. CBI, he said, is still collecting evidence and is interrogating many people. He rules out a judicial enquiry. Processions continue as Molvi Masoodi seeks identification of the relic.

In Khulna (Dacca), protests broke out and five people are killed. The army is out to manage the situation.

January 6, 1964

After 11 days, authorities make attempts at getting life normal. But the Action Committee makes identification of the relic a major issue. Pakistan plays it up. The Statesman carried a Rawalpindi dateline copy quoting an Azad Kashmir government spokesperson saying things contrary to India’s official position. “There were strong reasons to believe that the Indian claim of the recovery of the relic of the prophet was a hoax and an attempt at substitution,” he is quoted saying, terming it as “one of the most daring frauds in recent history.”

Bakhshi vouches of the relic’s genuineness but nobody listens.

January 7, 1964

Bengal belt is the most affected by the relic disappearance issue in Kashmir. Two more were stabbed in Daulatpur (Decca) as the strike continues in Kashmir.

Tony Mascarenhas reports from Delhi for Dacca based Morning News that “Bakhshi and his family are under virtual house arrest to prevent them from being torn to pieces by the angry people who are convinced that the finger of suspicion points heavily in Bakhshi’s direction for the sacrilegious theft.”

Indian Express reports from Amritsar that Praja Parishad’s Rishi Kumar Koushal says “the people suspect the hand of some influential persons in removing the relic.”

January 8, 1964

Editor Hindustan Times in his terse commentary suggests Bakhshi flew to Srinagar but stayed away from people. He said though he had broadcast his speech, it was given out that he had a public meeting. Besides, he accused Bakhshi of fleeing from Kashmir in a heavy escort during the night of January 3. Pakistan’s Dawn accused Bakhshi Rashid and his chauffeur directly for the theft.

Bakhshi, however, said the theft was “a diabolical and deep-rooted political conspiracy against India and Kashmir government and an attempt to discredit NC”. Talking to media persons Home Secretary V Vishwanathan said those demanding further identification “are speaking with the voices of Pakistan” asserting: “Such a demand would be in the interest of the malicious, mischievous, false propaganda that Pakistan is doing in the matter, thus would not be tolerated.”

January 10, 1964

After the relic was safely re-installed in the shrine, Shamsuddin announced public holiday, ordered illumination of markets and offices. A police Chowki sprung up around the shrine and police guard was deployed. Kashmir government gave one lakh rupees for making the shrine safe.

February 3, 1964

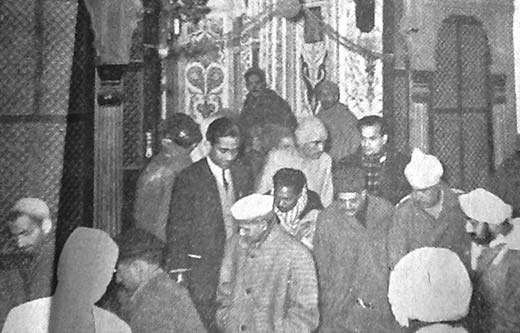

As the demand for identification does not die down, Nehru dispatches his trusted lieutenant Lal Bahadur Shastri to Srinagar. He offers Rs 101 to the shrine and starts negotiating with the Action Committee.

February 6, 1964

After detailed parleys, a limited deedar is organized and Syed Mirak Shah Kashani, a famous spiritual leader of Kashmir, heads a 17-member Action Committee group.

Crediting Shastri for his negotiating skills and persuading “the votaries of verification” against insisting on “shanakht (identification)” and offering “special deedar”, noted Indian journalist Inder Malhotra has given graphic detail of the tense moments in Indian Express on August 9, 2010, nearly half a century later he witnessed it.

“Maulvi Saeed Masoodi, a respected leader, took the microphone and asked the enormous audience: “Is there anyone among you who knows moo-e-muqqadas better than Mirak Shah Sahib”? There was total silence. Mirak Shah then came forward and held the recovered holy relic before his eyes for a full minute. The suspense during these 60 seconds would have surprised even Hitchcock. Then he bowed his head and said in a low but clear voice, “it is moo-e-muqqadas”. Wild cheers greeted him. The crisis was resolved but not the underlying issue,” Malhotra wrote.

But it was not over. The demand for the revelation of “real culprit” took over. Speaking to an intense debate in the Lok Sabha on February 12, Nanda refused to offer details about the accused. A day after, Atal Behari Vajpayee literally embarrassed him for not revealing the names but Nanda sought three more days.

It was February 17, 1964, that Nanda informed Lok Sabha that one of the five mujavir Banday brothers Abdul Rahim Banday had stolen the relic. In the theft, he said, his relative Abdul Rashid, a state government employee had helped him. It was later, he who was arrested while running away after he had kept back the relic. Third, Nanda said was Qadir Bhat, who has the history of coming and going to Pakistan. All were arrested. Banday, then 65, was bailed out on April 12. Action Committee members, however, asserted some of the accused were left unnamed.

Nanda also announced that a judge not connected with the state any way would preside over the trial. On January 31, 1964, the government appointed Nirvanan Singh as the judge to hear the relic case. On September 11, 1964, Nanda in Lok Sabha was denying Vajpayee’s allegation that Nehru government intends to drop the relic prosecution case.

On October 21, Singh was replaced by N K Hakak, district and sessions judge Srinagar. As a special judge, he had jurisdiction across the state.

On May 25, A A Aftab, district and sessions judge Islamabad was appointed as head of a commission of inquiry to investigate the firing of January 25, 1963. Only seven civilians had died in the entire crisis. The Commission got an extension on August 7. It was January 9, 1965, when the High Court stayed Aftab Commission’s order to place before it the correspondence between Srinagar and Delhi that took place during the crisis.

Malhotra having reported the crisis from the next day of the theft till Merakh Shah authenticated its genuineness, sums up the crisis like this. “Almost everyone knew that the imprisoned Hazratbal caretaker was a mere scapegoat,” he wrote in the Indian Express. “Apparently, a terminally ill lady in the Bakshi family wanted to have its deedar before dying. Unfortunately, its absence was noticed almost immediately.”

Kashmir apart, it was Bengal that bled severely because of the holy relic crisis. On February 11, 1964, Nanda told the Lok Sabha that while East Pakistan government has admitted 29 persons were killed in Khulna, Daulatpur and Khaluspur, unofficially the number is 200.

In West Bengal, rioting had led to 200 killings of both communities as police killed 56 in restoring order. Around 62000 people had lost their houses and 40000 were displaced of whom 5000 had migrated from West Bengal to the place that later became Bangladesh. There was return migration of Hindus as well.