Amid ceaseless complaints of torture, abduction and new age pellet assault in Kashmir, two documents released recently point out the ghastly security onslaught in valley. Bilal Handoo brings out the chilling details of the dual documents

The moment runaway unionists returned valley to participate in 1996 ‘Jashne Democracy’, a noted TV artist Bashir Dada too caught the electoral fever. But as the ballot failed to score over the bullet, Dada swiftly asserted that he was “forced” to contest the polls. But the claim faced the counterclaim from Liyaqat Ali Khan, Ikhwan commander. Behind these claims and counterclaims, there was a power structure operating from military camps. These camps would monitor the morsels of information fed to media and decision making in state’s security grid.

When all this was happening, Dada was a desperate man. In his desperation stage, Dada had his Hamlet moment, “to contest, or not to contest.” When it eventually became a question for him, he was visited by a henchman of Liyaqat Ikhwani, Mohammad Yousuf Dar. Dar eventually became Dada’s messenger, who informed Liyaqat, “Jinab, this man is unsure to contest polls.”

Liyaqat smirked, and sent some words of caution for Dada, “The only way out is to speak to the Boss.”

This “Boss” was GoC in Awantipora, Major General Shantanu Choudhary. Dada met him and explained his compulsions. The GOC understood. He asked Dada to join but told him that he necessarily needn’t do it. Later the general ordered Liyaqat and his Ikhwan wing, “Don’t trouble him, anymore!”

Dada’s rendezvous with army didn’t end there. He shortly needed army’s intervention to assist his neighbor and teacher, Ghulam Mohammad Shakir, who was a prominent Jamaat-e-Islami member. On face of constant harassment unleashed by Ikhwan, Shakir had migrated to Srinagar. But he wished to return home after being diagnosed with cancer. To clear the homecoming decks, he sought Dada’s help, who approached Liyaqat. The Ikhwani directed him to one Captain Clifton. After meeting him, Shakir was allowed to return home where he died of cancer within days.

This authoritative involvement of army in daily lives of civilians didn’t stop there.

Next time when Dada’s brother was arrested by BSF, he again sought security help. Through Liyaqat, he met JP Singh (reportedly SP of police’s SOG). Singh in turn called up a person named “Manoj” who turned out to be an army officer. It was this army man who finally secured the release of Dada’s brother.

Soon Dada was a disgruntled man exchanging heated words with an Ikhwani Setha Gujjar for misbehaving with his guests. The argument went out of control, involving police officers, RK Jalla and Ashkoor Wani. The issue was finally laid to rest by a Brigadier of Khanabal army camp.

Interestingly, army intervention to resolve disputes between Ikhwans, civilians and other agencies suggests their complete penetration and dominance. In South Kashmir, for instance, army from Khanabal army camp and Victor Force Headquarters at Awantipora had “control and command”. This ‘camp rule’ was in vogue at a time when army was sponsoring Ikhwan, says Syed Shah, an ex-MLA and brother of Shabir Ahmad Shah. Whenever anyone was arrested by Ikhwan, recalls Shah, he had to seek the assistance of army for their release.

This army-Ikhwan bonhomie emerged towards the fag-end of 1994 when Ikhwan was founded, says Liyaqat Ali Khan, the former Ikhwan head. This relationship with army emerged through a meeting with a Brigadier MP Singh at the Khanabal army camp. “For the initial six-eight months,” Liyaqat says, “Brigadier Singh was the person we met.”

An entire system was set up including individual groupings of Ikhwan across South Kashmir, reporting to individual camps. Once Liyaqat took over, he was seen attending regular army meetings. And with that Ikhwan spread like fire in Tral, Pahalgam…and other places, Liyaqat says. “Boys joined in. They joined from Al-Jehad, JKLF etc. We reached strength of 500 within 6 months. They all were working under our command. In the beginning no one was sure we would survive.”

But Ikhwan survived to the dismay of Kashmiris.

Behind its survival was the army support. Soon, Liyaqat termed as “Sector” by army got involved in political process. For political issues he dealt with a “General Dhillon” at XV Corps and subsequently he dealt with a “General Kishan Pal”. He was also constantly in touch with Home Minister and other government functionaries in New Delhi.

Being local, the value of Ikhwan who knew militants was to connect army to locals. “People became informers,” Liyaqat says. “Every day we would get 5 to 6 bits of information. We greatly benefited army through our intelligence gathering.”

For discharging these services, the Ikhwan received funds from the GOC, XV Corps and specifically General Kishan Pal. “Initially it was Rs 3000 per Ikhwani,” says Liyaqat, “but later it was brought down to the same level as the SPOs. But arms and ammunition were provided by the army…”

These revelations were made by the report Structures of Violence: The Indian State in Jammu and Kashmir released by International Peoples’ Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in Indian-Administered Kashmir and Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons on September 9, 2015 in Srinagar.

The report documents extra-judicial killings of 1080 persons and enforced disappearances of 172 persons. It names 972 specific alleged perpetrators directly concerned with identifying the structure, forms and tactics of violence in Kashmir.

While laying down the structure of army and BSF from the highest level, the report estimates the strength of the armed forces in Kashmir at 750981.

The report names a retired government employee from Bandipora as the oldest man to be subjected under enforced disappearance.

On June 19, 1997, at about 9pm, army personnel of 14 RR from Bandipora’s Chiternaar camp barged into the house of 67-year-old Ali Mohammad Mir at Dachigam, Bandipora, the report says. They entered the house and told the elder to accompany them for some questioning. Mir was taken inside the Chiternaar army camp. He never walked out of that camp.

Several youth who were mostly in their early twenties met Mir’s fate. Like a class 10 student from Wagoora Baramulla, Mohammad Iqbal Shah.

Shah was only 15 when he was picked up by BSF on March 13, 1995. His only crime was that he had resisted BSF beatings to his family members. After badly beaten, he was whisked away from home. Two decades have passed. He is yet to return home.

Another teen who won’t return home now was the 13-year-old Nisar Ahmed Najar of General Bus Stand, Islamabad.

In summer 1995, says the report, five Ikhwanis – Sheikh Tahir (alias Tahir Fuf), Sameer Darzi (alias Babloo), Showkat Muqam, Ghulam Rasool Wagay (alias Kach Gour) and Seth Gujjar – were forcing Najar’s elder brother to join Ikhwan, the offer he turned down. The refusal raged the renegades. They frequently raided Najar House. To escape assault, Najar’s brother migrated to Nawakadal, Srinagar.

Back home in Islamabad, Ikhwanis shortly detained Nisar on way to school. He was severely beaten. To save himself from beating, he told Ikhwanis, “We have weapons at home!” But they couldn’t find anything there. This turned Ikhwanis mad. They then started beating the inmates. Nisar was eventually taken to Malakhnagh area where he was shot dead. Later his one finger missing body was found abandoned on a road.

Equally shocking is the rape case in the report committed by an Ikhwani commander, Abdul Rashid Pahloo.

As an Ikhwan leader, Pahloo would force his entry into the victim’s house in Sumbal. “One day,” says the report, “he separated the girl from her family and took her to a separate room where he raped her.” Out of fear and shame, she didn’t disclose the dirty secret to her family. This continues for four months before another Ikhwani Bashir Rather alias Chengez followed his ringleader’s footprints.

Chengez took her to a separate room one day where she asked him for a grenade. She tried to remove its pin forcing the renegade to run away. And with that, she unburdened her heart.

Once her family knew it, they hid the grenade. Bashir Ikhwani misinformed Pahloo. The government gunmen began raiding the house and hung her upside down frequently.

Once BSF patrolling party spotted her hung to the ceiling. They entered her house and unfastened the rope. When BSF knew Ikhwanis were involved, they left the spot without saying anything. Meanwhile, her ordeal continued. “She was frequently dragged from room to room, beaten and molested by the Ikhwanis,” the report says. This nonstop torture took a heavy toll on her health forcing her family to hand over the grenade.

By 1993, the victim, now pregnant, was taken to the hospital. She died there after two days. “Her death was a consequence of the rape and torture,” the report says. Even then, no investigations were carried out. “Instead, Rashid Palhoo killed her brother in 1999 as he had apprehensions that he might take up the case of his sister.”

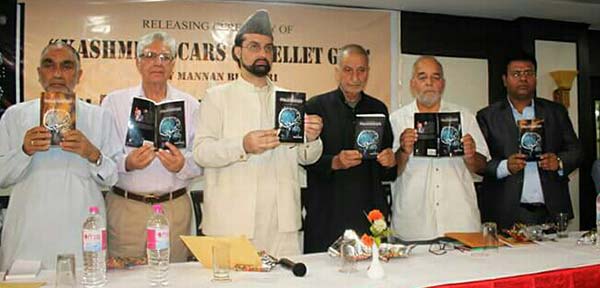

Kashmir’s transition from Ikhwan raj to street protests is marked with deadly pellets. Introduced during 2010 street uprising, the pellet guns have piled up Kashmir’s new age miseries. This truism has been documented in the recently released book “Kashmir Scars of Pellet Gun” compiled by human rights defender, Mannan Bukhari. “The significance of the book lies in collection and collating of data acquired through RTI, medical practitioner’s experiences and observations on pellet caused injuries and fatalities,” Bukhari says.

Of total 634 patients received between June and September 2010 at SKIMS Emergency Reception, the book says, 198 were pellet injuries. 19 pellet injured were inside SKIMS ophthalmology department from June 2010 to October 2013 – 15 of them required surgery. “In this military suppression, ‘catch and kill’ and ‘shoot to kill’, remained the norm for all these years and still does,” a noted activist, Gautam Navlakha writes in the book’s Foreword. The book asserts that the case of a 20-year-old Mudasir Nazir who became Kashmir’s first pellet casualty in 2010 is the offshoot of this mindset.

A class 12 student of Arampora Sopore, Mudasir on August 19, 2010, left home to offer evening prayers. A CRPF vehicle shortly fired cluster of pellet in his chest, abdomen and thighs perforating his whole small intestine. The deadly pellet wound eventually bled this only son of his parents to death.

“The book is coming out at a time when the inspector general of police (Kashmir) Javaid Geelani recently justified blinding of 16 year old Hamid by rhetorically asking, ‘How (else) can a deterrent be set then? How are stone-throwers to be stopped?’ ” Navlakha writes. “The fact that IG of Police in May 2015 finds blindings acceptable should remind us of the old adage that it is not guns that kill, it is man who kills.”