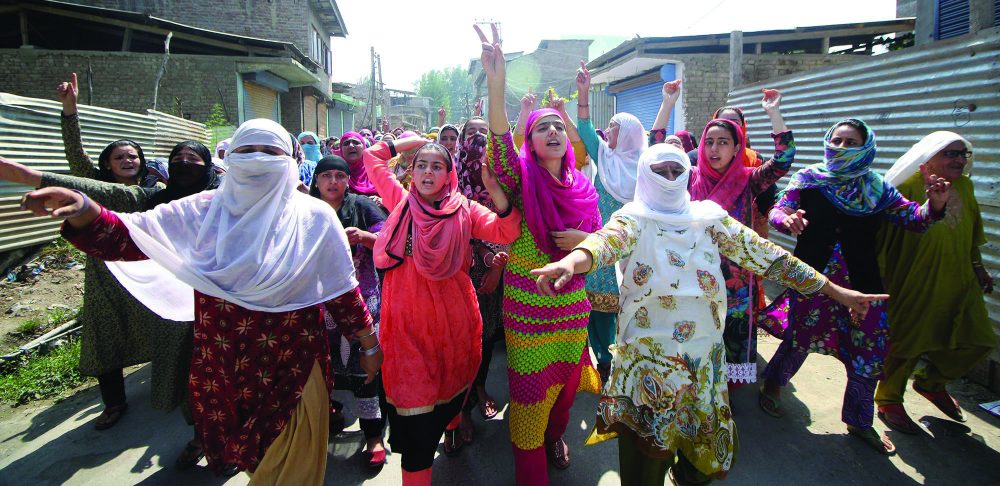

With protests already spanning over 70 days, Kashmir continues to exhibit resilience at huge cost. But lately the survivors of the harsh treatment and terrain seem to have left many tongues wagging with their idea of defiance, reports Bilal Handoo

Before Indian army’s Casper vehicles rammed lockdown residential gates in Kurhama Ganderbal on India’s I-day, the month-long shutdown had made the street force restless for a different reason. Whispers had grown loud and spilled to streets: “How do they manage meat everyday when they are under curfew?”

Then it happened. One by one, said a graduate Gul Asif of Kurhama, army stormed the homes to throw out electronic appliances. “The attack was spiteful,” said Asif, “as army men were frustrated seeing our unbending survival amid shutdown.”

But what happened in Kurhama isn’t an isolated incident. Several such incidents had already been reported and much talked about. But lately when an army major visited a Srinagar-based contractor at his Pampore workstation regarding a business deal, the very first thing he asked: “How are Kashmiris managing survival amid shutdown from last two months?” The major’s query didn’t surprise the contractor, like it didn’t those who keep hearing the street shrill. But as major businesses remain under lock and key at the moment, many say, the resilience isn’t only coming from streets.

In spring 2008, when a commerce graduate from Srinagar’s Tulsi Bagh setup his Macadam plant in Lasjan with Rs 2 crore investment, he never knew his maiden business venture would soon end in heartbreak with eruption of the land row. As Kashmir’s working season in construction sector remains limited (mostly from May to September), Muin Mir, the young unit-holder has already lost four working season since 2008 due to regular upheavals. “Doing business in Kashmir isn’t easy,” says Muin, who prepares 1km blacktop stretch at Rs 40 lakh cost. “My 5-month long uninterrupted season fetches me nearly Rs 20 crore.”

But despite suffering huge losses in present uprising, the new-age entrepreneur says Kashmiris have survived the worst and would emerge survivors, again.

With collective losses already running in thousands of crore, major trade activities in valley have already nose-dived. The prominent business house Khybar employing around 800 people incurs Rs 1 crore loss daily, an insider says. But despite the trade pundits sounding like prophets of doom, a strange hope continues to exist in society.

“After 2014 flood destroyed major parts of valley — especially Srinagar,” says Mushtaq Wani, KCCI president, “the resilient valley not only recuperated, but restored its lost glory despite analysts saying that floods have pushed Kashmir ten years down.” Wani says the valley exhibited the similar surviving spirit during hartals, curfews and economic blockades. “The beauty of Kashmiris is their ability to stand tall in tough times.” Kashmir’s well-known dissent pockets often living under stringent clampdown and restrictions have already exhibited that resilience.

In Palhallan, a 23-year-old boy still remembers how his buddy Adil Ramzan was shot inside the hospital after his life-saving drip was brutally pulled by paramilitary on July 30, 2010. The killing peaked Palhallan’s revolt at a time when a local army commander would warn school boys against taking part in protests.

“A lockdown for weeks that was enforced in Palhallan suffered it massively,” says Waseem, slain Adil’s friend. “But the village survived despite odds.” A mixed agrarian and artisan population, Palhallan continued facing curbs after 2010, but the “model village” stand resilient. “The resilience of civil society in Kashmir has ensured that morale has stood up despite the debilitating closure that Palhallan has been put through,” concluded a fact-finding team who visited Palhallan in late 2010. “But any complacence about the spirit of resistance being extinguished, would be grossly misplaced.”

But protests and hartal might be means of resistance, the strategy was always seen a “suicidal” by unionists and mainstream intelligentsia.

Terming protests, hartals and boycotts “self-defeatist” in nature, Dr Haseeb Drabu in a local function on June 14, 2014 said Kashmiris have to move out of the “politics of grudge”.

“I fail to understand this notion of hartals and boycotts,” Drabu said. “Who are we boycotting against? Who does it hurt? Through these hartals, you are only exhibiting your control over the Kashmiri population that has very little choice anyway.” But 2016 has already altered some of those notions after a public fury took the state off guard.

Soon the business community extended full support to the civil uprising led by the united Hurriyat. The corporate Kashmir said it was willing to sacrifice their businesses for resolving Kashmir dispute for sustainable peace in subcontinent. Even then, the state executives reckon the resilience is “grossly anti-people”.

“One fails to understand how the unending strikes would force India out of Kashmir,” said a youth PDP card-holder. “Frequent hartals have already dealt a crippling blow to Kashmir’s economy with financial losses pegged at over Rs two lakh crore in last 27 years.”

Since 1989 when armed uprising erupted in valley, around 2000 days of hartals and curfews were officially observed in Kashmir. The police figures reveal that Kashmir witnessed 198 days of shutdown in 1990 followed by 207 days of shutdown in 1991—highest so far. With gradual situational improvement, days of shutdown reduced to 24 in 1999 but again went up to 122 in 2001. In 2007, the lowest number of hartals was observed in valley when it remained shut for 13 days. In 2008 and 2010, Kashmir respectively witnessed 33 and 132 days of shutdown.

“We have suffered loss of over Rs two trillion due to hartals and curfews,” said Shakeel Qalandar, a prominent civil society group member. “Each day of hartal and curfew costs us Rs 100 crore.”

In view of economical impact of shutdown, the Hurriyat time and again termed Hartal a “compulsion”. “We are either being prevented from staging peaceful protests or kept under house arrest,” one Hurriyat leader evading arrest said. “It only leaves us with an option of hartal.”

But what seems to help sustain Kashmiris in protracted shutdown is its traditional weather response.

Harsh winter and highway blues have helped Kashmiri society to evolve a food reserve mechanism for years now. Besides weather, Kashmir’s chequered past has equally made it resilient. “Kashmir was only importing salt, tea and textile till 1953,” said Zareef A Zareef, a poet-historian. “That year, it lost its self-sufficiency label after Sheikh Abdullah was detained.”

When Abdullah was asked to import food grains from Punjab during 1951 drought, Zareef said, the late prime minister advised people to consume potatoes instead. “Abdullah felt that importing food grains would make Kashmiris dependent and vulnerable.” But despite suffering from dependency and economic erosion over the years, Kashmiris continue to exhibit resilience.

Today as the Kashmir’s economy relies heavily on service sector, many say the basic belief for being resilient is to rise from ruins. “After passing through bad phase,” said Muzaffar Mir, a doctorate scholar, “people do bounce back with resurgence. And this is what defines Kashmiris—for whom, resilience is actually an idea of resurgence.”

The display of this resilience even made the ex-guerrilla Azam Inqilabi to accolade Kashmiris in his typical ‘heavy’ words. “Kashmiri freedom votaries have determined to sustain the freedom struggle with invincible courage and unwavering resolve,” said Inqilabi. “Their monotheistic commitment and resistance resolve will remain juxtaposed to their initiative on various fronts of resistance. Their resistance resolve serves the purpose of a shock-absorber which guarantees the safety of driver and his automobile.”

Already the current uprising has mobilised people to donate ration, money for the needy. Especially youth are fervently gathering support to run community kitchens and volunteer works in and outside hospitals.

“Dream and destiny is liberty,” said Zubair, currently collecting monetary help for needy in Pulwama. “Till we achieve it, our duty is to help each other.” At many places, Baitul Maals have been setup for supporting the underprivileged sections of the society.

“Over 4 centuries of oppressive and degrading foreign rule, yet a people with an identity of their own,” said Arjimand Hussain Talib, a prominent political commentator. “27 long years of bloody conflict and still surviving. Most devastating flood of its modern times in 2014 and still coping. Today, the 60th day of shutdown, curfews and mayhem and still invincible. Resilience, thy name is Kashmir!”

On August 15, something else happened in Kurhama.

While rouging up the inmates, the army as per the eye-witnesses were heard chatting, “See how big their houses are and how many facilities they have? Yet, they are protesting!”

Perhaps what army men couldn’t figure out is how Kashmiris are presently putting their material possession in harm’s way for the sake of something immaterial.