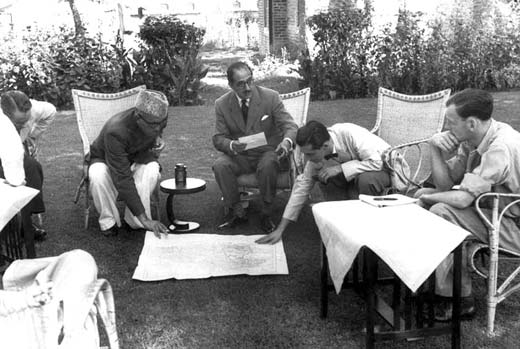

As experts are flying to Srinagar with suggestions and ideas, the invisible LoC is expected to shed a shaky fence for a stronger, impregnable and more visible divide. On the ninth anniversary of the ceasefire, Kashmir Life revisits the serpentine history of a line that divides families, culture and resources of a people historically victimized by the ‘great games’.

New Delhi’s ‘Line of Control’ (LoC) is still Islamabad’s ‘ceasefire line’, albeit unofficially. In Kashmir, it has many names. Separatists see it as a ‘line drawn in blood’. Even a unionist like former Chief Minister Mufti Sayeed once drew parallels of LoC with the erstwhile Berlin Wall.

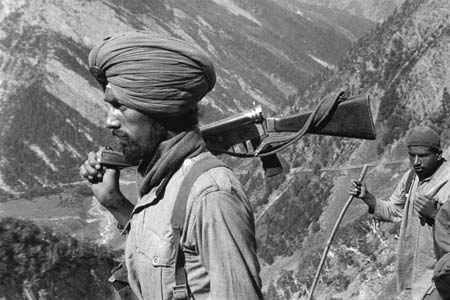

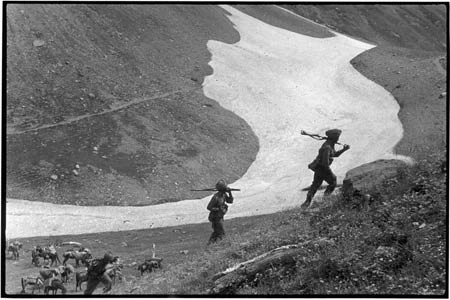

Whether LoC was a ‘geographic necessity’ or a ‘political blunder’, this political divider has remained a soldier’s nightmare because it is one of the world’s most active borders. After three wars and massive skirmishes over Kargil in 1999, rival armies calmed their roaring guns only in 2003. They frequently break the truce, sometimes in Poonch’s Krishan Ghati and more recently in the Haji Pir sector in Uri.

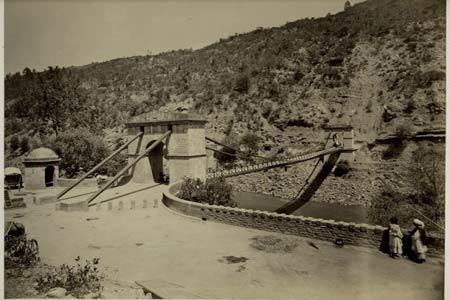

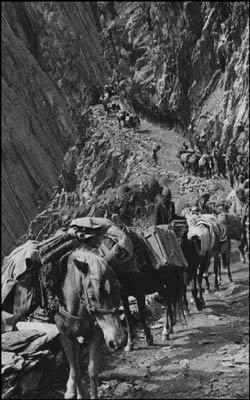

The LoC is the only constant of the post-partition Kashmir that defines and details its recent history. It owes its genesis to October 22, 1947, when the tribals crossed the Jhelum bridge at Kohala that marked the beginning of first Kashmir war between the just-born dominions of India and Pakistan. Though the Indian Army, on autocrat Hari Singh’s request and popular leader Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s support, stopped the raiders outside Srinagar in the last week of October, the war continued for the next 14 months. The fighting came to a formal end on January 1, 1949, after the UN intervened on Delhi’s request and the two sides signed a cease-fire pact, known as Karachi agreement on July 27, 1949.

The agreement defined the cease-fire line (CFL), as it was then called, in almost all the areas physically verified by the two sides. Its extreme point was traced in Baltistan (NJ 980420). Though the governments on either side of the line have historically staked claims on each other and even kept berths aside in their legislative bodies, the regimes used the line to push off their rivals and opponents.

In the 36-day war in 1965, the two sides occupied each other’s positions. One of India’s major victories was the capture of Haji Pir Pass, a high altitude mountain that divides Uri from Poonch and had offered the Pakistani army a dominating altitude, especially in Uri sector. Once wrested, the systems started functioning in the captured belts.

Master Hasan Din of Uri was one of the teachers who was posted immediately after in Khawaja Bandi, a village on the foothills of the Pass. “I had just passed the matriculation and was appointed as a teacher and my first place of posting was Khawja Bandi on September 8, 1965”, says Din, who retired from education department in May 2005 after putting in 40 years of service as a teacher. “I was one of the three teachers who were posted in the village after the army seized the Pass in 1965 war.”

This highly strategic pass, 22 km south of Uri, has seen intense fighting since 1947. Indian Army could not get its control in 1947-48 because a huge detachment with MMGs prevented any uphill movement. They, however, unfurled the tri-colour over it on August 28, 1965. Remembers Congressman Ghulam Rasool Kar who, as a state minister, accompanied Mrs Indira Gandhi to Haji Pir for a visit to Din’s Khawaja Bandi school, “The army convoys would move from Poonch to Uri and there was free movement of civilians”.

But the two countries agreed to a settlement known as the Tashkent Agreement on January 10, 1966. Under the agreement, the rival sides withdrew to the August 5, 1965 position by February 25, 1966. As status quo ante was restored, Din packed his jute mating and black blood and left the village in February 1966.

Restrictions apart, the human movements remained uncontrolled because families lived on either side of the line. Then the 14-day war of 1971 happened that saw the slicing of Pakistan and the emergence of ‘East Pakistan’ as Bangladesh. Rival sides altered the earlier positions and captured each other’s areas, more so in J&K that lacked international borders. The subsequent Shimla Pact on July 3, 1972 saw the CFL status becoming that of Line of Control. Later, on December 11, 1972, the two sides exchanged a set of 25 maps to identify the LoC that varied from the CFL position at many places.

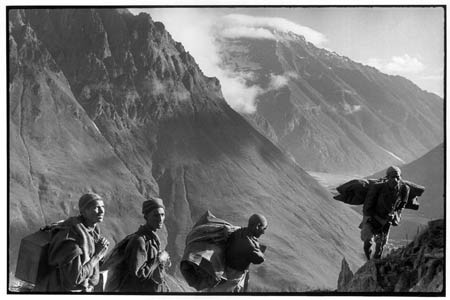

Unlike robotic armies, the individuals, especially at civilian levels are different and emotional. They take the divide and the change seriously. For the Indian army in Turtuk, a remote belt in Leh’s Nubra valley on the LoC with Pakistan, Hassan is always in demand. He was a recruit of Karakoram Scouts and fought against India in 1965. He retired in 1970 and was living in his Tyakshi village. A year later, this belt became India. For all these years, he is asking everybody only one question: why is he not getting a pension? When LK Advani visited the belt as Home Minister, he requested him to seek his rights as a soldier from Islamabad: ‘Did not I fight against India in 1965?’ Indian army has recruited his son Ali as a soldier.

Septuagenarian Ibrahim Abdul Rahman’s case is more interesting. He left his Turtuk village for Canada in 1960 as a Pakistani national. A globe trotter, he heard quite late that his home has changed sides. In 2005, when he was granted visa in his third attempt, he was permitted to enter India on a Pakistani passport. But he could not move beyond Leh. Hamlets like Chaknot and Fandoit knew of the division (of 1947) as late as 1963 when the rival sides starting confronting each other!

Post Shimla Agreement, the two countries remained busy in cold war but exhibited better civilian interactions at national and, to some extent, at sub-national levels. But in 1984, New Delhi reacted to cartographic interpretations suggesting as if Siachen was part of Pakistan. An operation was launched that led to the creation of the world’s only glaciated battle-field. Global strategic experts see this battle as a zero-sum game as good as two bald men fighting over a comb. India has repeatedly skipped the idea of restoring a status quo ante, the last assertion came in the 2012 summer. Now peace activists want this to be converted into a peace park but Indian strategic thinkers are staunchly supportive of the status quo.

The line does not follow any well defined geographical feature and often a home has its courtyard in India and structure in Pakistan. In Rajouri – Poonch belt of Jammu, there are 17 major villages which stand practically divided by the LoC. The line runs north-south from the Chenab Valley to Lunda in the Kishanganga Valley; it swings on an east-west alignment to the Indus River, and northeast to Karakorum Pass, the eastern terminus of the China-Pakistan boundary. The 1049-km long border dividing J&K from Pakistani administered territories, it may be recalled here, comprises 199 km of the international border (IB) between Pakistani Punjab and J&K, 740 km are LoC with PaK and the rest 110 km are actual ground position line (AGPL) on Siachen heights.

Unlike the rival soldiers, the people from two sides straddling the divide have very close bonds. During halcyon days, they would not need formal permissions from Delhi and Islamabad to meet each other. They were marrying within the clan after taking the field commanders into confidence. “The day I was supposed to get married in 1987, I took my horse to my uncle’s home (on the other side),” said a driver from Karnah working for a PSU. “As my family was looking for me, I came with loads of gifts that my uncle had promised.”

Of the total 275 families who are literally living on the LoC – enjoying (in certain cases) PaK power line and J&K water taps – 264 are in Mendar and Haveli area of Rajouri-Poonch. The LoC passes through as many 17 villages in the Rajouri-Poonch belt that is divided by 120 km of LoC from Pakistani Poonch. Defence forces came with relocation idea, firstly in 1967-68, but it invited a stiff resistance. In 1999, the proposal was re-opened to relocate 20 villages in Uri and 15 in Mendhar belt. But it could not take off.

The onset of militancy in 1989 witnessed the worst demographic upheavals in the border belt. To fight infiltration, security forces enforced a dusk-to-dawn curfew. When it failed, the 5-km-security belt running parallel to the LoC, was created in which literally no non-military life exists. Excessive measures led to massive migrations of over 35,000 persons but they continue to be missing in the discourse, both of the state government and the separatists. Generally, they are counted as ‘militants’.

Those who stayed put were living a life in hell. Since the fire exchange was routine for the rival sides, they would rarely see the day. They would live in dungeons and do not till their fields as snipers or shells would hit them. For many years, managing the population that lacked any productive activity near the LoC was a major problem for the government. In certain cases in Poonch, some villages were encouraged to migrate towards the hinterland. Their life was to survive in an 8 x 8 ft dungeon funded by the government at Rs 20,000 per family without light and fire. Before the escalations of tension in Kargil took the ugly turn, the government had funded around 2000 such dungeons in this district alone.

The equations changed in May 1998 when the two sides carried out nuclear tests which sparked global outrage and apprehension over the stability of the region. The subcontinent became the ‘critical mass’ to a level that certain Western media networks shot long TV series on this theme. As New Delhi thought the nuclearization would prove a deterrent, Islamabad’s response forced a new balance of power.

The Kargil ‘war’ in 1999 magnified the tensions and delayed a possible reconciliation and de-escalation between the two countries. For the time being, it dictated a new security regime in J&K. Ultimately, it led to frustration within the jingoistic circles in Islamabad that India can be forced to a settlement.

The first thaw, however, came in November 2000 when the then Prime Minister announced a unilateral ceasefire. The non-initiation of combat operation (NICO) was primarily aimed at taming the insurgent within but had its implications across the divide. It lasted between November 28, 2000, to May 21, 2001, and helped people on the ‘borders’ to see a ray of hope.

As guns stopped, rival armies started permitting people, divided by turmoil, to get near the LoC and weave up towards their relatives on the other side. In Keran belt where over 1047 people have migrated so far, the troops permitted the locals to reach one of the banks of the Kishan Ganga river to have a glimpse of their relatives – the practice still being followed. In this part of Kashmir, it is Neelam river (Kishanganga) that is the literal LoC dividing the pre-partition Keran into two halves – Chahlan (PoK) and Teetwal (J&K). Having a distance of only 50 meters, a wooden bridge that was connecting the two sides was blasted from the Pakistani side. But the river with intense cold waters has not frozen the blood of the kin divided by it.

At the peak of NICO bonhomie, one day when the divided relatives were waving towards each other from the two banks, a young housewife overwhelmed by emotions jumped into the river as the two crowds cheered her to swim back home to Keran. She tried but failed and was washed away by the freezing cold waves. Lot many civilians living on the other side of the LoC returned home in Uri’s Lachipora, Gohalta, Nambla, Silikote and Kamalkote hamlets.

But the peace did not last long. The parliament attack on December 13, 2001, triggered a larger crisis. Though all the five militants were gunned down, Delhi gave marching orders to the Army. Under operation parakram, when both countries moved its fighting machines near the border in January 2002, it was the biggest build-up since 1971.

J&K had its own share in the crisis. In more than 200 villages on the IB and LoC, people had to migrate. The Army took over 70,100 acres of land in Jammu, Kuthua, Rajouri and Poonch districts alone and converted around 25,000 acres into landmines. This was in addition to the 26,985.75 acres (including 23123.75 acres in Kashmir region) that the armed forces had occupied between 1989 and 2000.

Skirmishes became a routine and the buildup threatened a larger conflict. The exercise was costly – Rs 6500 crore for New Delhi and $ 1.4 billion for Islamabad. India lost 798 soldiers during the mobilization, without fighting a war. Managing the civilian population far away from their homes added to the costs. By October 2002, demobilization started.

This paved way for a better understanding. The real thaw came on November 26, 2003, when Vajpayee government announced a ceasefire on the LoC. Though it was negotiated through back-channels, the agreement was just an understanding between the rival armies. The truce came so abruptly that people directly affected by the shelling had no time to decide how they should respond. Villagers in Pallanwala sector (Jammu) came out with drums on the streets to celebrate the silencing of rival mortars. Darshan Lal, a villager from Jammu’s Arina village came rushing from the migrant camp he was living in for the last three years, only to see the wild grasses have taken control of his agriculture land. He started clearing it and a mine exploded blowing off his appendages. He was 2003’s 30th civilian who lost his limbs in mine explosions.

In Suchetgarh, people had an interesting complaint. They could not sleep because there was no booming blast sounds the whole night they were used to. Some of them slept during the day until they became acclimatized to the calm of the night.

Nine years down the line, the ceasefire is still holding. On the eve of its anniversary last week, the rival sides “celebrated” the occasion in Poonch’s Krishana Ghati by firing at each other’s positions. The forest in between caught fire!

Ceasefire did wonders. It helped resume routine life after a decade or so. And then the fencing of the LoC went into the fast forward mode.

Fencing LoC was part two of the project. Given the success with which the fence worked in Punjab, the project was extended to the IB in J&K. By the time the first pole was erected at the LoC, half of the length of the IB was fenced in Jammu.

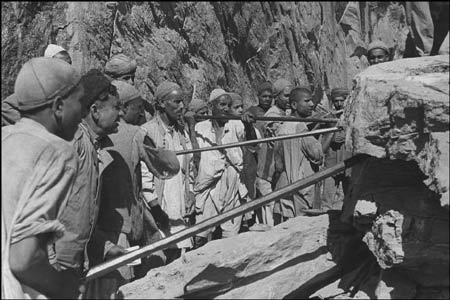

The project belonged to CPWD but for three years Pakistani gunners did not permit them to work and they fled. In January 2001, BSF decided to implement the project suo moto. Using bulletproof bulldozers, air-conditioner fitted excavators and taking the cover of a 15-feet high wall, BSF did it successfully.

Initially, the Army tried to raise the fence near the LoC but raining guns from the Pakistani army prevented it. It is not an ordinary structure. An engineering feat that cost the defence ministry more than Rs 1100 crores, every single kilometre of fence requires an aggregate 260 tons of cement, iron pickets and steel wire. It is 12-feet high fencing of the LoC barrier that snakes around the zigzag LoC and comprises two fences with an eight-foot gap in the middle filled with coils of razor-sharp concertina wire. Apart from having the option of being electrified, it has some sophisticated electronic gadgets, mostly imported thermal imagers and sensors, that offer a sound alarm system if the fence is fiddled with.

Islamabad compared it with the “Israeli fence” and tried to project the LoC fencing as “violation of the UN resolutions and all the bilateral agreements”. Taking it as an effort of converting LoC into a working border in the long run, it had even sought the intervention of the UN and other countries. But the response was discouraging. Refusing to term it bad, US State Department’s then-spokesman, Richard Boucher said, “I guess I have to reject the contention that it (the Indian fence) is just like (the Israeli fence) in the Middle East. I think these are two different fences”. European Union’s Foreign Policy Chief, Javier Solana viewed the logic of the construction of the LoC fence entirely different from that of security wall being built by Israel. Instead, he saw the fence as an “improvement in technical means to control infiltration”.

While LoC became visible, it came with its own problems. A lot of population was trapped between the actual LoC and the fence. Poonch-Rajouri wherefrom the fencing started is perhaps the best instance that explains the crisis.

Wazir Mohammad is one of the thousands of people representing the new underdogs of Kashmir society.

They carry I-cards distinctly different from the other people living closer to the LoC across the state. As a formal barrier restricts their movement, they sustain life differently.

Haji Akbar Hussain has lost connections with his in-laws. “I live in Bagal Dara and my in-laws are from Dokri. It would usually be an hour-long trek from my village but not any more,” Hussain said. “Both the villages are fenced and now I have to come out of fence and reach Poonch and then take a vehicle and reach another gate of fence at a different place, then go for a long trek and meet them. It is a day-long affair now.”

In Mandi area, says lawyer and PDP leader, Imtiyaz Ahmad Banday, the fence was barely 100 meters from the local tehsil office. In certain areas like Kerni, the entire population comprising 515 families were moved out and temporarily settled far away from the zero line and much farther from their hearths and fields. Fence forced a new routine for the border people!

“It was more of the official routine – going at 8 am and returning by 5 pm,” said Ghulam Nabi in Mendhar. “Farms are unlike offices, they require a round the clock commitment.” Poonch historian Khush Dev Maini says the district’s 27,000 people in 42 villages are divided by the fence. “People have no social life,” he said, “Fence opens only after the laid down norms are completed and sometimes in emergencies they do not open at all and that is the mess.”

Fencing has started paying the dividends. Within a few weeks, after it was erected, around 11 infiltrators who got entangled in the series of wires that make the fence in Poonch and Rajouri sectors were killed. Ajaz Ahmad Jan, the young National Conference lawmaker who represents Poonch in state legislature said the fence has snapped the roots of militancy in Poonch. “But we need to take care of the people who are stakeholders, now.”

“When India and Pakistan agreed to a ceasefire, it was the major shift in the hostilities that reduced the problems of our citizens,” said Jan. “Since there is no shelling going on, it is high time the fence is taken to the zero line and it will have a major positive impact on the situation.”

It was this peaceful situation that led to the opening of the LoC for travel of divided families in 2005 and for trade in October 2008. The twin initiatives continue to be the only Kashmir specific development in the subcontinent since 1947. Both the initiatives, however, are suffering for one or other reasons.

During all these conflicts – low intensity and wars, the UNMOGIP gradually lacked its relevance. Though it has been gleefully accepting the memoranda from Kashmiris for the UN, the situation seems to have neutralized the mandate.

The first dent happened in 1971, a watershed year in the history of Kashmir. It did not only push CFL aside and create the LoC, it immensely dented the status of UNMOGIP as the ‘third empires’ and the ‘peacemakers’. Since the Shimla agreement, India is not offering any cooperation to UNMOGIP, unlike Pakistan. The only cooperation they are getting is hospitality and security. During the Kargil war, their office in the sector was closed for security reasons.

The army detachments milked from various non-aligned armies had always a trust deficit. There are interesting anecdotes involving the UNMOGIP members caught in the divide, literally. Lt Gen Maurice Delvoic, a Belgian military adviser to the first UN mission in the subcontinent took seven boxes of valuables to a lady in PaK (who was later identified as the wife of a person declared an enemy agent by J&K) in 1949 and lost his job the same year. US navy Commander J Cadwaladar, who was part of UNMOGIP, was recalled by the UN Security Council for delivering a message of a father to his daughter in Srinagar!

More recently, on October 31, 2001, UNMOGIP’s then Austrian Chief Military Observer Major General Hermann K Loidolt triggered a near crisis when he accused India and Pakistan of playing games with Kashmir. “All of us are aware of the situation in Kashmir and the games both parties (India and Pakistan) are playing with this tormented country. We all know there is no easy solution and especially war is absolutely no solution for Kashmir….. It will be an issue for the US to solve it,” General Loidolt said. “May it be diversionary manoeuvre on the Pakistani side to make India the real enemy instead of the US, or may it be the dawning of next election in India. It is an issue for the US to solve it.” After a bit of crisis, he apologized and was shifted.

Amid bilateral bonhomie and occasional thuds at LoC, New Delhi is planning a stronger fence. The central government is sending a high-level delegation to the state to examine the proposal and make necessary recommendations. It will have engineers from the Army, Central Public Works Department and National Buildings Construction Corporation. Their objective is to study the feasibility of erecting an all-weather fence that can withstand snow avalanches and heavy snowfall. Almost 80 km of the existing fence is prone to severe damages during winters either under the weight of snow or by avalanches that are so common to the LoC, especially in north Kashmir.

Raising a permanent fence may quieten the borders temporarily but whether the ‘permanent’ divide translates into any political dividends for the two countries is anyone’s guess!