In 1965 summer, when army was flushing out Pakistani infiltrators in the city suburb, Batamaloo went up in flames. Half a century later, the survivors of the conflagration tell Bilal Handoo the different aspects of the historic event that changed the locality forever

Ten days before Batamaloo went up in flames, a fainted woman in summer 1965 was rushed to the clinic of Pandit Prithvi Nath, the only registered medical practitioner of Batamaloo. A resident of Gangbugh, the woman shocked everyone once swung back to senses: “Some gunmen have arrived in our village.” Even for the peasants of Batamaloo, the news was scary.

That unidentified female couldn’t withstand the sight of men with rifles and was advised to keep quiet. But her silence didn’t prevent Pakistanis from raising alarm over Batamaloo. Their presence in the town, however, was debated, and subjected to rumours.

As rumours ran rampant, a seventh standard student was getting ready to participate for August 15 rehearsals in his school, the function still 10 days away. But excitement of Mohammad Sidiq Sofi ended shortly after he was bolted awake from sleep during one night when gun shots rang in Batamaloo first time in that summer of discontent.

That night Sidiq heard his terrified mother venting her anguish: “Perhaps that lady at Nath’s clinic was right. Mujahids have indeed arrived in Batamaloo.” As such thoughts ran wild, says Sidiq, now a retired teacher, “we couldn’t sleep throughout that night out of fear.”

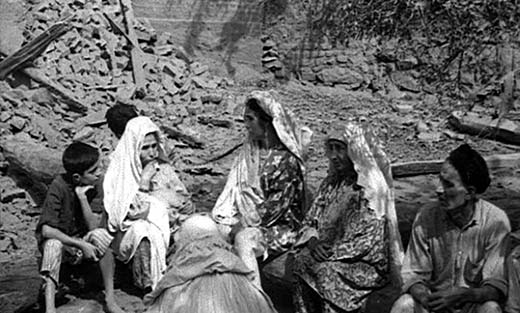

By dawn, Batamaloo was edgy. Men, women and children were fleeing, abandoning everything. Sidiq remembers it as a kind of a mass migration triggered by gunshots during night and a strong word of mouth during day about an imminent gunfight between mujahids and military in the area.

But Sidiq’s family stayed put. Their neighbour passed away preventing their departure. As dusk fell over, the family braved another nightmare of fireworks.

The next morning, Sidiq’s father stepped out to get milk and bread. He disappeared. Without waiting for his return, the family shifted to old city’s Khanqah Mohalla. Two days later, the father reappeared. He went on to reveal how he was detained by patrolling soldiers outside his home. “I was blindfolded, handcuffed and beaten on my way to Toto Ground,” Sidiq heard his father saying. “Later I was shifted to Badami Bagh Army Cantonment along with dozen of locals.”

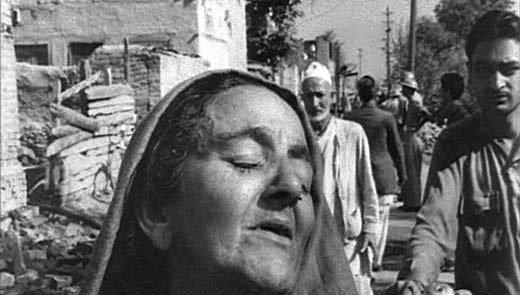

Two days later came the shocker. Batamaloo was set on fire. Angry men from old city tried to take out a protest march towards the burning place but were cut short by police. Out of curiosity, the young Sidiq mounted on a bicycle, rode through old city’s congested lanes to reach his Mohalla, only to see half of it up in flames and smoke. Batamaloo was reduced to smouldering rubble, recalls Sidiq. It was a nerve-jerking moment for the locals pouring in to access damages of their abandoned houses.

Later The Washington Star reported on September 1, 1965 that the entire Batamaloo inhabited by Muslims was razed to the ground during the past three weeks. Fire had consumed around 440 houses, it reported. “Many Muslims were burnt alive in this suburb by the Indian Army. Indian officials claim Pakistani infiltrators started the fires. But both extremist and moderate Kashmiris and the victims themselves, interviewed while digging in the smouldering wreckage, claim the Indian army was responsible.”

And then, under smoke-filled skies of Batamaloo, something very intriguing happened.

One night, locals say, army arrived and pasted posters on the charred walls. The next morning people crowded to get the glimpse of blindfolded men tagged as militants on posters. They detected some of the locals who were arrested, photographed, released and framed.

But the truth is the young Sidiq never saw any militant roaming or hiding in Batamaloo town. “But yes,” he recalls, “militants were spotted at suburbs, like in Gangbugh, Tengpora, Narrekour where they signalled their arrival by killing one local cop.” When the funeral of that slain JKP constable Abdul Rashid was being taken out from Batamaloo bazaar, Sidiq heard the streets voices speculating how Rashid, posted near Bemina bridge, saw some men angling in the area. Upon questioning their presence and purpose, he was shot dead.

The young Rashid’s killing had chilled Batamaloo.

But while suburbs had ominous militant signs, the main town known for its hustle bustle never saw them coming. While anticipating their arrival, a perpetual sense of fear of coming in the line of fire was disturbing locals. It was the same fear that shortly went on to terrorize an otherwise ‘brave’ local carpenter.

A night before Batamaloo turned into ghost lanes, the carpenter Bahadur Ahmad Najar heard a single gunshot while sleeping inside the attic of his house. After a brief lull, a barrage of bullets rattled Batamaloo. Bahadur trembled in fear like his family members. “Such was the horror of the night,” he recalls half a century old event with rapt clarity, “that most of us pissed in our trousers.”

The next day in restive Batamaloo, Bahadur met a colleague, alarming him: “What are you waiting for? Just leave! Army is about to wage war here. They have positioned cannons towards the town.” As fretful Bahadur fled, he couldn’t make sense of army’s war intentions in the abandoned locality.

The next morning, Bahadur had a reunion with his father and brother, whom he had left behind while fleeing, at Ganpatiyar Habba Kadal where the family had taken temporary shelter. In a trembled state, Bahadur heard his father saying how they spent the past night hiding in a heap of sawdust at home.

Amid fear, Bahadur realised that something was rotten in the Batamaloo town. Later his fears turned true when people began talking about some ‘deep state’ at work in Batamaloo during ’65 summer. Behind this street talk was the pattern: nocturnal gunshots, short-term disappearances, heightened visits of army and defence sleuths.

Some instances did fuel doubts. From Dhoobi Mohalla, a man was caught by army and was told to torch some residential houses days before the big blaze. “Even in detention, many locals were projected as captured militants,” says Ghulam Qadir, a retired teacher from Batamaloo who too faced detention.

The string of events got people a whiff of some political conspiracy. “I believe,” continues Qadir, “after failing to stop the stride of marching Mujahids from Pakistan up to Batamaloo suburbs, the idea was to burn the town to restrict their movement into city.”

What further cemented this belief was the timing of the fire. With Pakistan celebrating its independence day on August 14 (’65), top army commanders and the state government decided to incinerate Batamaloo, thought to be under Pakistan control.

In Batamaloo, like other places, people were listening to Sadai Kashmir, the clandestine radio station, which started broadcasts as the tensions began. It was apparently launched to rouse passions and pass on information. “One day, it made an announcement that armed rebellion broke out in Batamaloo, asserting that Pakistani soldiers in civvies have taken over Srinagar,” Qadir remembers. As per the radio news, Pakis were just 2km away from the civil secretariat.

But the fire eventually forced them to retreat thus dooming Op Gibraltar. Later General Musa Khan, then commander-in-chief of the Pakistan army wrote in his book My Version that the Kashmiris weren’t taken into confidence about the operation aimed to liberate them. “The best opportunity (for) our freedom has been lost,” Munshi Mohammed Ishaq, a close confidante of Sheikh Abdullah, later asserted.

However the miscommunication cost Batamaloo very dearly, Qadir says. After August ’65, Batamaloo was never same again. Some people never recovered from the losses they suffered. People were barred from reconstructing their gutted houses, later paving way to bazaar and bus stand. Chief Minister GM Sadiq, a Batamaloo local, allotted paddy land for reconstructions besides giving Rs 4000 aid and Rs 6000 loan. But rebuilding couldn’t prevent the town’s crash from self-sustaining community to a mere consumer market.

As fortunes flipped, resentment rose. But the town refused to change. Some days after ’65 fire incident, a lady spotted a wounded mujahid lying near the water ditch in Khelwear Batamaloo. Posters were already out asking people to hand over militants to police for cash. “But state could never tempt Batamaloo,” says Qadir. It was out of this conviction that made the locals to come out in horde and to give a safe passage to the wounded mujahid back to Pakistan.