In 1947, Kashmir was literally independent for many fortnights. After rumours about the major princely state joining India, there was Poonch rebellion and tribal raids soon after. As Nehru, Patel and Lord Mountbatten were to get Kashmir accede to India, a British journalist who headed The Statesman newspaper, was fiercely against it, writes journalist Saeed Naqvi

My Kashmir narrative begins with Ian Stephens, editor of The Statesman from 1942 to 1951, the years of the Quit India Movement, the end of World War II, Partition and the commotion that followed everywhere, including in Kashmir. I have settled on Stephens as my witness to avoid an Indian or Pakistani bias in the story. After a double first at Cambridge, Stephens joined the British government’s Information Bureau and was soon handpicked as the editor of The Statesman, the most powerful newspaper in the Empire at the time after The Times, London.

Mountbatten, Nehru, Patel, Jinnah were all dramatis personae in the mishandling of Partition and, later, Kashmir. Stephens knew them all personally and yet he was professionally equidistant from them. Stephens was an athletic, outdoorsy man who would bicycle from the Swiss Hotel, Civil Lines, where he stayed when in Delhi, to The Statesman office in Connaught Place. Otherwise his residence was the Statesman House, Calcutta. He was passionate about Pathans, particularly his orderly, Karim, his ‘companion of fourteen years’.

On 28 October 1947, when the Kashmir issue was heating up, Stephens published an editorial which caused a sensation. Before I get to that historic editorial, let me provide the background.

Earlier that month, Stephens had moved from Calcutta to Delhi to have a ringside view of developments relating to Muslim dominated Kashmir ruled by Maharaja Hari Singh. Tangentially, the kingdoms of Hyderabad and Junagadh (both Hindu majority states ruled by Muslim rulers) also came into focus.

The big question post-Independence was this: where would these states opt to go? Would they choose to join Pakistan or remain with India? The Nizam of Hyderabad wanted his state to be an independent entity but India sent in troops and annexed it. The Muslim ruler of Junagadh wanted to go with Pakistan but India had the decision reversed since it was a Hindu majority state. So what about Kashmir? The Maharaja of Kashmir, Hari Singh, did not wish to go with Pakistan; he wanted to accede Jammu to India and later hold a plebiscite in the region where Muslims were in a majority. Hari Singh allegedly hoped to alter the demography of his kingdom by ensuring that a chunk of the Muslim population would be eliminated or pushed out of Jammu to Pakistan, thus placing Hindus in the majority. But that left Kashmir in contention—Pakistan insisted it was theirs because it had Muslims in the majority. India, on the other hand, was not willing to part with Kashmir because it had now been incorporated into the Nehruvian secular argument.

Stephens knew Mountbatten well. He first met Mountbatten in 1943 soon after he reached India as ‘supremo’ of the newly created South East Asia Command (SEAC). In fact, Stephens had done Mountbatten a favour by publishing the SEAC newspaper under The Statesman’s roof. Mountbatten became Governor General of the Indian Dominion on 15 August 1947.

So piqued was he with Jinnah for denying him a piece of history as Governor General of Pakistan, that he began to settle scores with Jinnah even on sensitive issues like Kashmir.

Nehru, as history tells us, had made his ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech at the stroke of the midnight hour on 14-15 August. Two nations had been created in too unseemly a hurry for a matter so important. The oppressive heat of August was giving way to September. Just at this moment, Stephens noticed the beginnings of what was about to go seriously wrong where Kashmir was concerned. Stephens deserves a hearing because he had predicted how Kashmir was going to spell ‘big trouble’ for all concerned.

Let me quote a passage by Stephens:

“When I read in September that Mr Gopalaswami Ayyangar, a very able and reputedly anti-Muslim Madrasi Brahmin who was the prime minister of Kashmir from 1937 to 1943, had been made Minister without Portfolio in the new Indian Cabinet, I said to our editorial conference in Calcutta: ‘That really does look as if India’s up to something at Srinagar’, and our correspondents were told to watch for news.”

In fact, Stephens had seen earlier pointers to ‘something’ happening in Kashmir. In the run-up to Partition, Acharya Kripalani, President of the Congress party, some princes from East Punjab, and Mahatma Gandhi had visited Kashmir. The editor of The Statesman attached much significance to the Mahatma’s visit. He felt Gandhiji was a ‘saintly man’ but was also ‘one of the world’s most ingenious politicians; it was hard to think what could have drawn him, as a saint, to Srinagar at that moment.’

Meanwhile, rumours had been reaching Delhi since July 1947 that Maharaja Hari Singh was looking for an opportunity to accede to India although his subjects were overwhelmingly Muslim. Stephens refused to go by the unconfirmed reports that he was receiving but there were too many of them, he noted, ‘to be ignored.’

Ved Bhasin, later editor of the Kashmir Times, who was a student leader in Jammu in 1947, recalls what transpired. It confirms Stephens’s observations. Bhasin’s is not a spur of the moment emotional outburst, but a carefully worded and objective account from someone who was once a member of the RSS. He committed his memories to a paper (Experiences of Partition: Jammu 1947) presented at the Jammu University in 2003. Bhasin recalls that after the 3 June Plan there was pressure on Maharaja Hari Singh to accede to India or Pakistan from both the Congress and Muslim League Leaders.

In this backdrop Gandhiji visited Srinagar on August 1, and met the Maharaja. Though Gandhi declared that his mission was not political and he was only fulfilling an old promise to the Maharaja to visit Kashmir, there were clear indications that he had advised him to join the India Union. Gandhiji returned to New Delhi via Jammu where he arrived on June 3.

As far as Stephens was concerned, rumours were soon replaced by ‘authentic news’ in September of a large-scale insurrection by Muslim peasants, many of them ‘recently-demobilized soldiers’, in the Poonch region. They were revolting against oppression by the Maharaja’s officials. This was, according to Stephens, an ‘oppression long known, which had at one time appeared to distress Congressmen much more than the British bureaucracy.’ But Congressmen were not interested on this occasion.

The insurrection was an important development but was ignored by the media of the day. Reports about it were deliberately killed in the newsroom since it was feared that publishing such stories might renew bloodshed and promote communal discord.

The other reasoning was that Poonch was anyway a remote, hilly, inaccessible region from where news hardly filtered out so the reports could be censored. As a result, news of the insurrection went to the dustbin on what Stephens called ‘higher humanitarian’ grounds. No one wanted to stoke the fire.

But trouble continued to brew and spread. By October, reports started coming in of trouble around Jammu. The Muslims there were said ‘to be in flight, having been terrorized and in places cut up by Sikhs and Hindus, at the instigation of the Maharajah’s officials.’ The news could no longer be concealed. So Stephens moved to the Delhi office to get a better sense of what was going on.

Once in the capital, he met General Roy Bucher, Chief of Staff of the Indian Army, who told him that the ‘Kashmir climax was upon us indeed—and for a startling new reason: Pathan tribesmen had burst into the western part of the State. The message had just come, and [the General] said everyone was in a flap.’

That same evening, 26 October, Stephens was asked to dinner with the Mountbattens who had invited a select few. He was shocked by what he saw. Here is what he recorded in a memorandum after the dinner:

“I was startled by their one-sided verdicts on affairs. They seemed to have become wholly pro-Hindu. The atmosphere at Government House that night was almost one of war. Pakistan, the Muslim League, and Mr Jinnah were the enemy. This tribal movement into Kashmir was criminal folly. And it must have been well organized. Mr Jinnah, Lord Mountbatten assured me, was waiting at Abbottabad, ready to drive in triumph to Srinagar if it succeeded. It was a thoroughly evil affair. By contrast, India’s policy towards Kashmir, and the Princely States generally, had throughout been ‘impeccable’.”

The contrast was glaring when Mountbatten showered praise on Nehru for his restraint on Kashmir. He felt that it was ‘high-minded’ of Nehru to have promised a plebiscite after the Maharaja’s accession.

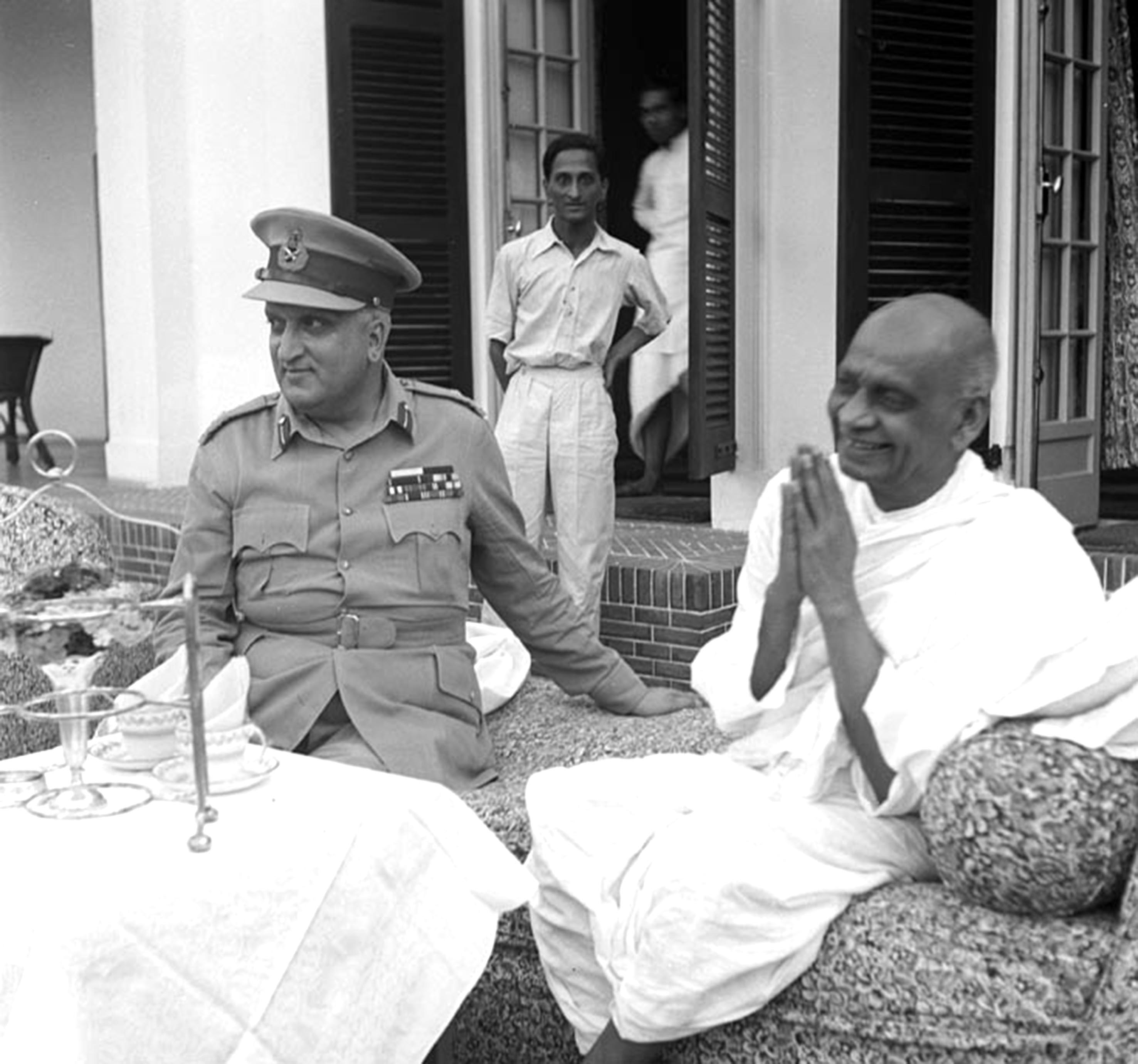

The next day Stephens met Deputy Prime Minister Sardar Patel with whom he disagreed on various issues but whom he respected for being cordial and frank. ‘Five minutes with him [Patel] was in my experience worth fifteen with Pandit Nehru.’

The Statesman editor wrote in his notes after the meeting that ‘undercurrents in his remarks seemed only to confirm my surmise that India’s policies towards the princely states had not been wholly “impeccable”, in aim or method.’

Stephens, as the editor of an important paper, was briefed by Mountbatten on the ‘facts’. He was told that, because of the Pathan attack, Maharaja Hari Singh’s formal accession to India was being finalized. ‘Subject to a plebiscite, this great State, its inhabitants mainly Muslim, would now be legally lost to Jinnah. Indian troops were to be flown into Kashmir at once; arrangements had been made. This was the only way to save Srinagar from sack by ruffianly tribesmen.’

Mountbatten told him that Kashmir had many Europeans and attacks on them had already been reported. Stephens recorded in his notes that the Governor General was ‘persuasive, confident, charming, a successful commander on the eve of an important operation, who manifestly banked on hustling The Statesman into complete support.’

Stephens was ‘flabbergasted’ by what he was told. He felt Kashmir was too sensitive and important a state to be handled so arbitrarily. He put these thoughts on record:

“The whole concept of dividing the subcontinent into Hindu majority and Muslim-majority areas, the basis of the June 3 Plan, seemed outraged. At a Hindu Maharajah’s choice, but with a British Governor General’s backing, three million Muslims, in a region always considered to be vital to Pakistan if she were created, were legally to be made Indian citizens.”

When Mountbatten took Stephens aside it became an exercise in the former influencing the latter to see value in the way India was proceeding. An ailing Jinnah had been outfoxed by a formidable team—Mountbatten, Nehru, Patel, Gopalaswami Ayyangar and so on.

Stephens found himself in a dilemma after Independence. Should he report honestly about what was happening in Kashmir or should he exercise extra caution to accommodate Mountbatten’s biases? Should he hold back when it came to looking at the nascent Indian government and its actions critically?

He explains his dilemma:

“Here then, far too soon after Independence to be healthy, for The Statesman or me, was a major issue on which it seemed that the new India had decided wrongly, and deserved criticism. Should I criticize, and if so how? On so big a topic we must express some opinion. But for a British-owned paper to disagree with the new Indian Government, still so sensitive and raw, was another. Clashes with Authority are indeed at times an essential part of an editor’s job. During my term of office we had, for instance, disagreed sharply with Lord Linlithgow, in the autumn of 1942, over the then important matter of Mr Rajagopalachari’s request to see Mahatma Gandhi in jail, and with Lord Wavell, and indeed the whole Cabinet Mission in June 1946. But they were British, we were British, and we felt strong enough to do this; how strong were we now?”

Like a good journalist Stephens added up the pluses and minuses. He saw the Pathan incursion as an outrage; many of the tribesmen, in their rush towards Srinagar, had behaved shamefully, killing burning, looting. And if the Indian claim that the attack was arranged by Pakistan was true then it was a reprehensible act.

But he felt Pakistan would have to be questioned properly before arriving at a conclusion. He also felt that Pakistan’s acceptance of accession by the Nawab of Junagadh was ‘absurd’ and the first affront to the general principles of the 3 June Plan. But India already had Junagadh under economic and military blockade.

If, as seemed likely, she occupied it, her cause for grievance there collapsed—and with it also much of her legal claim to be in Kashmir.

Stephens also put under his scanner the doctrine of secularism or non-communalism, already being pressed as the justification for India entering Kashmir, a Muslim-majority area. Stephens felt:

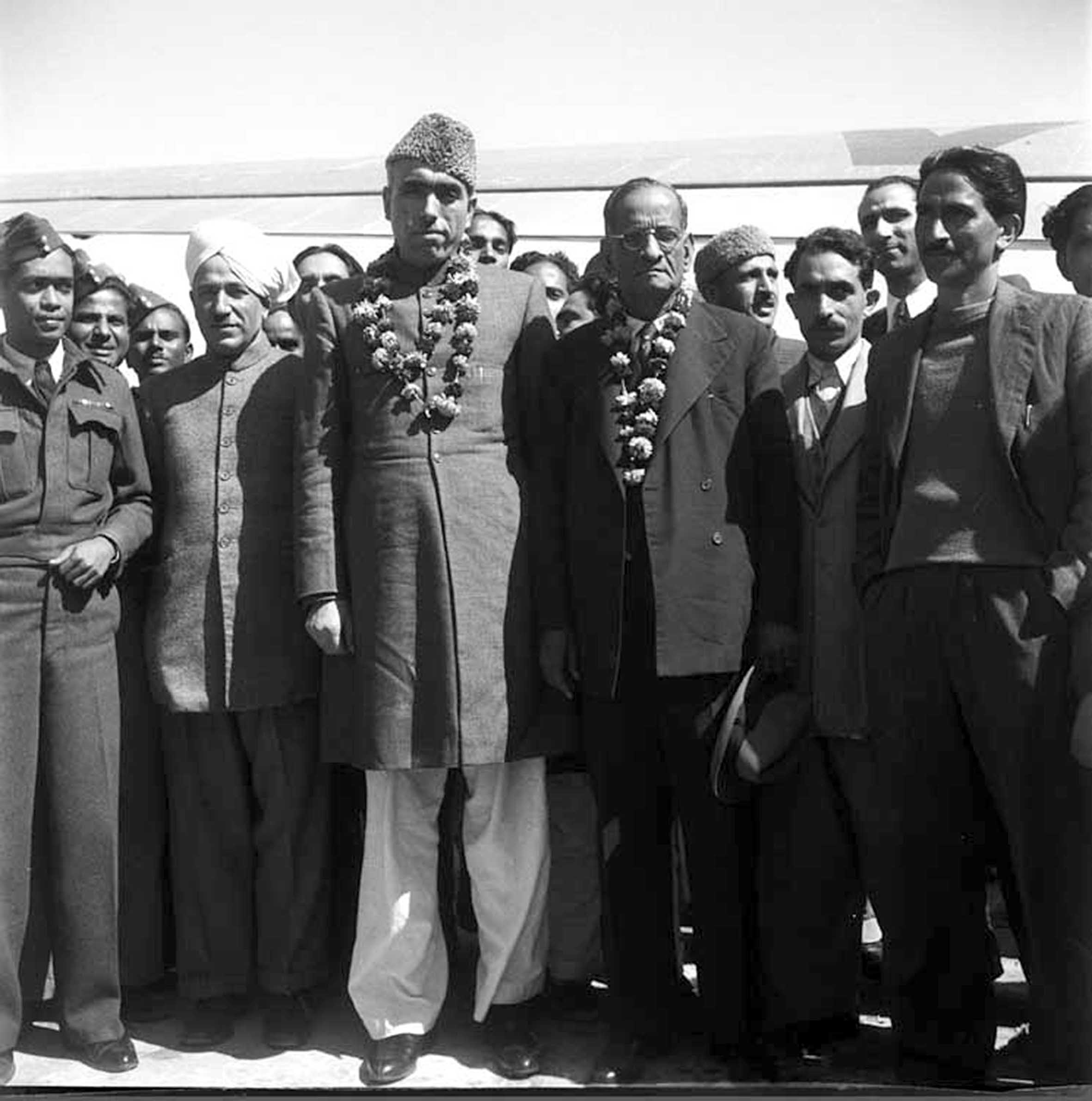

“If it worked it was an admirable doctrine, and Sheikh Abdullah, who had been chosen to head the administration in India-held Kashmir, seemed from his reputation a good instrument for it. But it had notoriously failed to work, and had therefore been set aside under the June 3 Plan, throughout the Provinces of British India. Would it really work in Kashmir? Why should such an exception be tried?”

The editor then looked at the minuses. He noted that the Pathan raid was not the only such incident in Kashmir. He also felt it may perhaps not have happened if there hadn’t been bloodshed in Poonch. In effect, he seems to suggest that the Pathans had rushed to Srinagar in retaliation for the attacks on Muslims in Poonch. Stephens goes on to note:

“Casualties among the innocent on both sides might be much bigger than in the Pathan raid; no one yet knew, owing to the bad communications. And now horrible rumours were arriving, too many to be baseless, of organized eviction and slaughter of Muslims around Jammu, with the Maharaja’s alleged approval, an affair which perhaps had been in motion before the Pathan raid was launched. After Stephens examined the pluses and minuses of the Kashmir crisis he came to the conclusion that The Statesman could not support the Indian government as Mountbatten had expected.”

The result was the editorial Dangerous Moves which irked Mountbatten. Reproduced here is the 639-word piece dated 28 October 1947 that shook the Governor General.

“Both the new Dominions have been behaving rashly about certain of the States to the probable detriment of the common people’s peace and happiness. Pakistan began it. Her acceptance of Junagadh’s accession, though justified legally, and perhaps by a long stretch of the term geographically— communication between them being practicable by sea—was ludicrous ethnologically, little Junagadh’s population being (like Hyderabad’s) predominantly Hindu. Such conduct seemed explicable only as a short-sighted, spiteful gesture to annoy India, or as a planned subtlety of much wider bearing.

On either count it was unstatesmanlike, unworthy. India’s reaction however, in our view, lacked balance, a shortcoming manifestly attributable to the acute mutual suspicions between the two Dominions. Though the bigger, stronger of them, who should therefore be scrupulous to eschew any temptation to bully, she responded by unseemly military display—backed, it is said, by economic blockade—and by publicly magnifying into a major crisis an affair relatively small and silly, which could, we believe, have been suitably handled with gentler and unhurried fingers.

But the Kashmir affair is by no means small. That State ranks among this country’s biggest, and fills a region of exceptional strategic importance on the map. If—as much evidence suggests—last week’s alarming incursion of armed Pathans into its Western part had the Pakistan authorities’ tacit support, that is disgraceful, and will constitute a lasting slur on the new Dominion’s fair name. But it also, if true, displays a strange unintelligence, for it has forthwith had the effect, which might have been foreseen, and which surely the Pakistan government cannot have wanted, of catapulting the Kashmir Durbar into the arms of the Indian Union.

We view the prospects now created with profound misgiving, as must all of detached outlook who yearn for abatement of suffering and strife on this populous subcontinent. Kashmir’s accession to the Indian Union, despite the undertaking about later voluntary withdrawal of the Union’s troops and influence, makes no better sense than did Junagadh’s to Pakistan. Both arrangements run flagrantly counter to realities. Whether India, without hazard to her own precariously re-established internal peace, and to movements of pitiable Punjab refugees, can effectively help her new protégé to restore order if the incursion has been truly formidable remains to be seen. Air transport can do much nowadays to win access to mountain-girt country.

Nevertheless, her armed forces, though larger and stronger than Pakistan’s, are over-stretched, and (like Pakistan’s) much disorganized by partition.

The talk about plebiscites—for Kashmir and, by unmistakable implication, for Junagadh—though theoretically attractive, may not mean much in practice. Such things need much organizing, and are difficult to complete fairly and peacefully. Last summer’s, in the NWFP and Sylhet, stirred strong feeling; and those were held in what was British India, under impartial plans devised before the country was split. Such conditions no longer exist; and it is not easy to see how plebiscites in faction-ridden States such as Kashmir and Junagadh, even if honestly conducted, could be otherwise than widely suspect.

The logical outcome from an unnatural tangle obviously would be that the rulers of Junagadh, and in due course of Hyderabad, should make up their minds to join the Indian Union, and of Kashmir to join Pakistan. The present topsy-turvydom whereby each new Dominion has gained accession from a state inhabited by a majority of contrary communal composition is too brittle and absurd to endure.

Meanwhile a public, tragically aware of how strongly passions are running, and of recent unprecedented carnage, can but hope for statesmanship from both Governments. Pakistan’s reaction to India’s forward move will be awaited with anxiety.

The dismal, deep, damnable fact must be faced that the two Dominions now stand perilously poised before what, whether so declared or not, would be war—a war which neither would be able to sustain militarily or economically without ruin.”

Within hours of the editorial appearing, Stephens received a summons. It was not a cordial meeting with the Governor General, as Stephens recalls in his book Horned Moon: An Account of a Journey Through Pakistan, Kashmir and Afghanistan:

‘The Governor-General’s press attaché, Mr Campbell-Johnson, telephoned; would I please come to see His Excellency? During the ensuing interview, The Statesman was in effect threatened with death, on the Indian Cabinet’s behalf, unless it adopted a more pro-Indian line…expressing the gravest displeasure, Lord Mountbatten declared that “by this article”, (I quote from my memorandum), [W]e had done serious public disservice. After all the trouble which he (Lord Mountbatten) and Mr Patel had taken to explain matters, they had found themselves that morning ‘hit for six—yes, Sir’. Amazement had been voiced in Cabinet, by Mr Patel and others. It had been impossible for him to defend me. He had felt much embarrassed and annoyed, having previously tried hard to build up in his colleagues’ minds the notion that a British-owned newspaper in the new India was needed. Did I suppose that Mr Patel, after being hit for six in such a fashion, would ever now do anything for us? And so on.

After his angry outburst, Mountbatten went on to share ‘important news’ with The Statesman editor—there was to be an interdominion conference about Kashmir at Lahore the next day.

But that conference did not take place. In fact, it turned out to be a ‘fiasco.’ It was first postponed and then Nehru could not attend because he was indisposed. Sardar Patel expressed his inability to leave Delhi to attend the conference in Lahore.

Stephens cheekily adds that Patel, though being busy, ‘managed relatively long trips to Srinagar and Junagadh’. All this seems to suggest that the Congress leadership was averse to participating in inter-dominion jamborees where a sensitive issue could be brought up. They had got what they wanted. With Mountbatten around, things were going their way.

On 30 October, Stephens called Mountbatten’s press adviser Campbell-Johnson to convey to the Governor General that he had considered the issue carefully and could not change his views about Kashmir. He also added for good measure that as long as he was editor he would ‘try to uphold an inter-Dominion policy, rather than to support one side.’

The indomitable Sardar Patel could not tolerate such an affront. When Stephens exceeded limits and published an ad released by Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir (PoK) in The Statesman, the Iron Man of India politely asked Stephens to return home for good.

(This essay is edited excerpt from Kashmir related chapter of journalist Saeed Naqvi’s book Being the Other: The Muslim in India)