A British author T R Swinburne along with many of his friends was visiting Kashmir when they were caught in the floods in 1905, two years after the Great Flood. Back home, he wrote his ‘A Holiday In the happy valley with pen and pencil’ that Smith, Elder & Co, 15-waterloo place published in 1907. It has 24 colour illustrations including two drawn during floods. Though the book has many references to the devastation that floods wrecked, Kashmir Life reproduces the chapter XIII of the book that exclusively tackles the historic floods.

Tuesday, September 12.—A second edition of the Noachian deluge is upon us! It began to rain on Saturday, at the close of a hot and stuffy week, and, having succeeded in thoroughly soaking the unfortunate ladies who were engaged in a golf competition that day, it proceeded to rain abundantly all through Sunday and Monday.

The outlook from our hut is dispiriting; through a thick grey veil of vapour the gleam of water shines over the swamp that was the polo-ground. The little muddy stream in which so many erring golf-balls lie low is up and out for a ramble over its banks. The lower golf-greens resemble paddy-fields, and round the marg the spires of dull grey pines stand dripping in a steadfast shower-bath.

Sometimes the heavy cloud folds everything in its leaden wing, blotting out even the streaming village at our feet, and reducing our view to the immediate slope below us where the wilted ragwort and rank weeds bend before the tiny torrents which trickle everywhere. Then comes a break, falsely suggestive of an improvement, and lo! soaring above the cloudy turmoil, the lofty shoulders of Apharwat sheeted in new-fallen snow!

After the somewhat oppressive heat of last week, the sudden raw cold strikes home, and Jane and I take great interest in the fire; the “Old Snake” is an accomplished fire-master, and it is pleasant to watch him squatting like an ungainly frog in front of the hearth, and sagaciously feeding the flame with damp and spitting logs.

It is amazing what lavish expenditure of fuel one can indulge in when it costs nothing a ton!

We are just beginning to find out the exact spots where chairs may be planted so as to avoid the searching draughts which go far to make our happy home like a very airy sort of bird-cage.

Well! we might have been worrying through all this in a sodden tent, where even a boarded floor would barely have kept out rheumatism, and where one would have been liable to alarms and excursions at all sorts of untoward times when drains wanted deepening and guys slackening.

The mere thought of such things sent us into a truly thankful state of mind, and we discussed from our cosy chairs the probable condition of the party from the Residency which set forth, full of high hope, on Saturday morning to attack the markhor of Poonch.

Here it has rained with vehemence ever since they left; up in the high ground it has doubtless snowed; our pet name for Shikari Mark II, who reigns in the stead of Ahmed Bot, sacked for expensive inefficiency. And although they were well armed with cards and whisky, yet it would appear but a poor business to play bridge all day in a snow-bound tent on the top of the Pir Panjal! Nothing short of a hundred aces every few minutes could make the game worth the candle!

This spell of bad weather has greatly interfered with the movements of a large number of the folks who were to leave Gulmarg early this week. Many got away betimes on Saturday, and a few faced the elements on Sunday, and a painful experience they must have had.

We had intended to leave next Thursday, and had ordered boats to meet us at Parana Chauni, but the road will be so bad that I wired this morning to put off our transport till further orders.

The end of the season at Gulmarg sees the bazaar stock at low water. Eggs, fowls, cherry brandy, and spirits of wine are “off,” also butter, but the latter scarcity does not affect us, as we make our own in a pickle jar. The bazaar butter became very bad, probably because the large numbers of visitors to Gulmarg caused an additional supply to be got from uncleanly Gujars, so we, by the kindness of the Assistant Resident, had a special cow detailed to supply us daily with milk at our own door.

That cow was very friendly; I first made its acquaintance one forenoon. While I was sitting below the verandah sketching, with a dozen lovely peaches spread by me on the boards to obtain their final touch of perfection in the sun before lunch, the cow strolled up. I was much interested in the sketch, and believed that the cow was too; but when I looked up at last, expecting to see its eye fixed upon the work in silent approbation, “The ‘cow’ was still there, but the ‘peaches’ were gone.”

In the afternoon the weather showed signs of a desire to amend its ways. The clouds broke here and there, and, though it still rained heavily, it became apparent that the clerk of the weather had done his worst, and the supply of rain was running short. Clad in aquascutic garments, and surmounted by an ungainly two – rupee bazaar umbrella (my dapper British one having been annexed by a covetous Mangi)—”Ombrifuge, Lord love you, case o’ rain, I flopped forth ‘sbuddikins on my own ten toes.”

The whole slope in front of the hut was a trickle of water, threading the dying stalks of dock and ragwort, and hurrying down to add its dirty pittance to the small yellow torrent rushing along the greasy strip of clay that in happier days was the path.

The whole marg was become lake or stream—lake over the polo-ground and half the golf-links—fed by the weeping slopes on every side, whence innumerable nils rioted over the grass, emulating in ferocity and haste, if not in size, the tawny torrents which drained the sides of Apharwat.

The road from the bazaar to the club was all but impassable, but as it had still a few inches of free-board, I followed it to the foot of the church slope, and, skirting the hill, inspected the desolation which had been wrought at the Kotal hole, where the stream had torn through its banks and wrecked the green.

During a visit of condolence to Mrs. Smithson, whose unfortunate husband is pursuing markhor in Poonch, the sky cleared—a splendid effort in the way of a “clearing shower” being followed by a decided break-up of the pall of wet cloud in which we have been too long immersed. Not without a severe struggle did Jupiter Pluvius consent to turn off the tap, but at length the sun broke through the hanging clouds and sent their sodden grey fragments swirling up the Ferozepore Nullah to break in foamy wreaths round the ragged cliffs of Kulan.

Finding the road across to the post-office altogether under water for some distance—a lake extending from the twelfth hole for nearly a quarter of a mile to the main road— wandered back towards the higher ground, joining a waterproof figure, a member of the Green Committee, who was sadly regarding the waterlogged links with the disconsolate air of the raven let loose from the ark!

We agreed that this was a remarkably good opportunity for observing the drainage system, and taking notes for future guidance, and in company we went over as much of the links as possible, finishing below the second hole, where the cross stream which comes down from the higher ground had torn away the bridge and cut off the huts beyond from civilisation.

The homeward stroll at sunset was perfectly beautiful, and showed Gulmarg in an absolutely new guise. The lower part of the marg, being all lake, reflected the lustrous golden sky and rich dark pine-woods in a faithful mirror. Flying fragments of cloud, fleeces of gold and crimson, clung to the mountain-sides or sailed above the forests, while beyond Apharwat, coldly clad in a pure white mantle of snow, new fallen, rose silhouetted against the darkening sky.

Saturday, September 16.—After the Deluge came the Exodus, everybody trying to leave Gulmarg at once. We had always intended to go down to Srinagar about the 15th, but, finding that the Residency party meant to move on that day, we arranged to migrate a day earlier in order to avoid the pony and coolie famine which a Residential progress entails on the ordinary traveler.

On Wednesday afternoon the ten ponies, carefully ordered a week before from the outlying villages, were congregated on the weedy slope which falls away from our verandah, picking up a scanty sustenance from decaying ragwort and such like.

Secure in the possession of the necessary transport, Jane and I strolled forth for a last look at Nanga Parbat, should he haply deign to be on view. He did not deign, however, preferring to remain, like Achilles, when bereft of Briseis, sulking in his cloudy tent. So we consoled ourselves with an exceedingly fine view of the snow-crowned heights at the head of the Ferozepore -Nullah.

Upon returning to our beloved log cabin we were met by Sabz Ali—almost speechless with wrath—who broke to us the distressing news that six of our ten weight-carriers had departed from the compound.

The entire staff, with the exception of our factotum, were away in pursuit, and there was nothing for it but to possess our souls in what patience we might until they returned.

As we had arranged for a four o’clock start next morning, it was most disconcerting to have all our transport desert so late in the evening. An urgent note to the Assistant Resident, and some pressure on the Tehsildhar, produced promise of assistance.

Early on Thursday morning came an indignant chit from an irate General, complaining that my servants were trying to seize his ponies, for which he had paid an advance of two rupees, and would I be good enough to investigate the affair.

Here was the murder out. His chuprassie had obviously bribed my pony wallahs, and a letter, stating my case pretty clearly, produced the ponies and an apology.

This delay kept us till after midday, when, stowing our invalid snugly in a dandy, we left Gulmarg and began the descent to Srinagar. I remained behind to see the hut clear and make a sketch, and then hurried down the direct path, which drops some 2000 feet to Tangmarg.

Here I found Jane and the invalid comfortably disposed in a landau, but the baggage spread about anywhere, and the usual clamour of coolies up-rising in the heated and dust-laden air. Weary-looking mule, appeared on the scene, and we seized upon it instantly, loaded it up with most of the baggage, and dispatched coolies with the rest.

After the storm came a holy calm, and we settled down to a light but welcome lunch before starting down the long slope into the valley. We had heard most disquieting tales of floods; the water had burst the bund at Srinagar, and there was said to be ten feet over the polo-ground.

The occupants of Nedou’s Hotel were going in and out by boat, and Srinagar itself was said to be quite cut off from all access by road. The Residency party has countermanded their intended move tomorrow.

At the post-office I was told that only a small part of the mail had been brought into Srinagar, the road being “bund” between Baramula and that place, while an unusual number of landslips and bridges have come down in the Jhelum Valley.

Nevertheless, we had made a push to get on; things in Kashmir are often less gloomy than their reports would make one believe, and so we bowled quite cheerfully down the road from Tangmarg, basking in the hot and sunny air, which seemed to us really delicious after the raw cheerlessness of the last few days at Gulmarg.

From Tangmarg to the dak bungalow at Margam, a steady descent is maintained by an excellent road over the sloping Karewa, for about ten miles, of which we had just about travelled half when a series of yells from the scene behind, a wild swerve, and a heavy plump brought us up just on the edge of the steep and rocky bank, which fell sharply from the roadside.

Alas! The axle of the off hind wheel had snapped, and the wheel itself was hopelessly lying in the thick white dust, and our landau looked like an ancient three-decker in a squall.

The horses being unharnessed, we sent the drivers with one of them forward to look for help, and Hesketh and Jane proceeded to make tea while I sat by the roadside and sketched.

Presently an empty dandy came “dribbling by” on its return journey to Gulmarg, and it was immediately impressed for the benefit of the lame. Hardly had we packed him in, when a wandering tonga hove in sight, and, being promptly requisitioned, we rattled off the five miles which lay between us and Margam in no time.

Here we found a large party assembled in the little rest-house. Colonel and Mrs. Maxwell (who had kindly sent us back the tonga on hearing of the breakdown); Mr. and Mrs. Allen Baines, whose dandy had been the means of bringing Hesketh along; and Sadleir-Jackson, and Edwards of the 9th Lancers.

The bungalow was full, but I found out that one room was appropriated by a coming event, who had cast his shadow before him in the guise of a bearer. This being contrary to the etiquette as observed in dak bungalows, I gently but firmly cleared out the neatly arranged toilet things and ready-made bed; while Hesketh was taken over, somewhat shattered by his tedious though exciting day, by his fellow Lancers.

The resources of the little place were severely strained; dinner was a scanty meal, and soda-water gave out almost immediately: nevertheless, a cheroot and a rubber of bridge sent us contented to bed.

Yesterday (Friday) the question of how to proceed arose. The road was reported to be impassable after about five miles, the remaining ten being under water.

We set out after breakfast, Jane perched on a pony which Sabz Ali had raised or stolen, Hesketh in the dandy, and I on foot. After a warm five miles’ march we came upon signs of a block. Vehicles of many and strange sorts were drawn up in the shade of a chenar, under whose wide branches the Baines family was faring sumptuously on biscuits and brandy and water.

Horses, goats, and cattle strayed around, and a chattering mob of natives, busily engaged, as usual, in doing nothing, completed the picture.

Hesketh was reduced to despair; after two months in bed, this could not but be a trying journey under the most favourable circumstances, and the prospect as held out by his pessimistic bearer was pretty gloomy— no boats available, and no signs of our doungas.

I pushed on to the break in search of my shikari, whom I had sent on by pony early in the morning, and soon found that estimable person, who is not really the Withering idiot he looks!

In the first place, he had appropriated the only two shikaras he could find, and our baggage was already being stowed in them; secondly, he had discovered both juma and Ismala, our Mangis, who reported the doungas moored below Parana Chauni, about four miles away over the flooded fields.

This was good news, and we ate a cheerful lunch under a tree densely populated by jackdaws.

The Maxwells got away somehow in search of their house-boat, which was supposed to have left Baramula some days ago. They started cheerfully, but vaguely, down the Spill Canal, and we trust they found their ark somewhere!

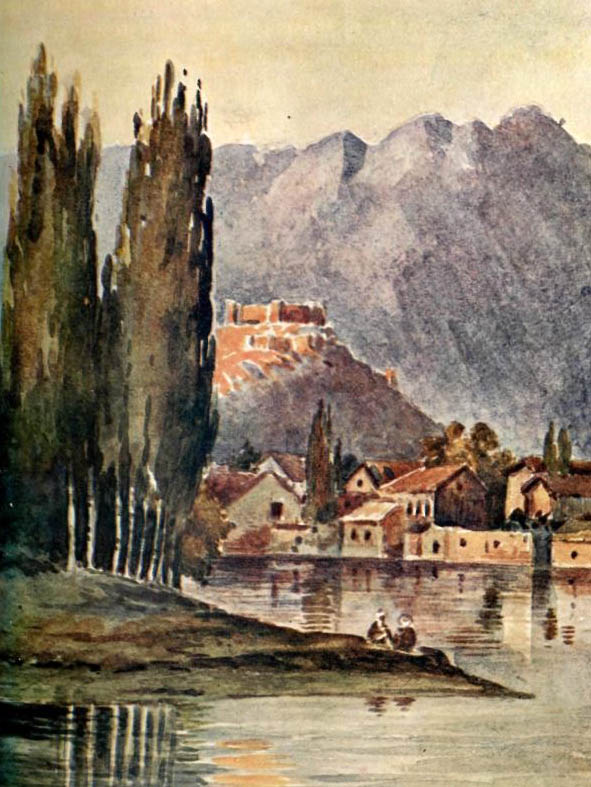

Promising to send back a boat for the Baines, we paid and dismissed coolies and ponies, and paddled away over the flood water. The country was simply a vast lake, the main road merely marked by a dense row of poplars. Trees rose promiscuously out of the calm and sunlit water, wisps of maize and wreckage clinging to their lower boughs. Presently the road showed in patches, a broad waterfall breaking it every here and there as the imprisoned waters from above sought the slightly lower channel of the Jhelum.

We passed a party of natives bivouacking near the roof and upper storey of their wooden hut, which, floating from above, was held up by the Baramula road.

Sounding now and then with our khudsticks, we found no bottom over the submerged rice crops, though we could see plainly the laden ears waving dismally down below. This is nothing less than a great calamity for the owners, as the rice was just ready for gathering.

Towards dusk we arrived at our ships, calmly lying moored to poplar trees by the roadside, and right gladly did we clamber on board, for our invalid was pretty

well fagged out.

This morning we cast loose from our poplars, and brought the fleet up to within half a mile of the seventh bridge, or, rather, of the spot where the seventh bridge

used to be, for all but a fragment has been washed away! The strong current prevented us from getting any higher up the river in our doungas.

Jane and T, however, were anxious to see what appearance Srinagar presented, so we manned the shikara with five able-bodied paddlers and pushed our way upwards. Turning into a side canal we passed a demolished bridge, and tried to force our way up a small but swift stream.

Failing to make anything of it, we landed and had the boat carried over into a wider channel. Three times we were obliged to get out and leave our stalwart crew to force the boat on somehow, and they did it well—hauling, paddling, and shouting invocations to various saints, particularly the one whose name sounds like “jam paws!”

The water had already fallen some four or five feet, but there was plenty left. A great break in the bund between Nusserwanjee’s shop and the Punjab Bank allowed us to paddle into the flooded European quarter, past the telegraph office, standing knee-deep in muddy water, up over the main road to Nedou’s Hotel, where boats lay moored outside the dining-room windows, then across the lagoon, lightly rippled by a tiny breeze, beneath which lay the polo-ground, to the Residency, where we landed to inspect damages.

The water had been all over the lower storey, but a muddy deposit on the wooden floor, and a brown slimy high-water mark on the door jambs, alone remained to show what had happened. The piano had been hoisted upon a table, carpets and curtains bundled upstairs, and everything, apparently, saved. The poor garden, with its slime-daubed shrubs, broken palings and torn creepers, trailing wisps of draggled foliage in the oozy brown pools, was a sad and pitiful sight, especially when mentally contrasted with the glowing glory of asters and zinneas which it should have been.

The flood has been nearly as bad as the great one of 1903. Fortunately the Spill Canal, cut above Srinagar to carry off the flood water, took off some of the pressure; the bund, also, is three feet higher than it was then, but it gave way in two places—one somewhere near the top, and the other just below the Bank, letting in the river to a depth of ten feet over the low-lying quarter.

The stream is now falling fast, and, after doing a little shopping and visiting the post-office, which is temporarily established on the bund in the midst of an amazing litter of desks, boxes, and queer pigeon-holes admirably adapted to lose letters by the score, we spun swiftly down the rushing stream to tea and our cosy dounga.

Monday, September 18.—It was impossible to get our boats up the river yesterday, so I spent the day sketching amidst the most picturesque, but horribly smelly, part of the town; much quinine in the evening seemed desirable as a counterblast to possible malaria.

The sunsets lately have been really magnificent; the poplars and chenars, darkly olive, reflected in the flooded fields against a red gold sky; in the foreground the black silhouettes of the armada.

The days are almost too hot, but the nights are cool and delicious, and the mosquitoes are only notice-able for a brief period of sinful activity about sundown, after which the wicked cease from troubling and the weary are at rest.

At half-past ten this morning we set sail; that is to say, we hired nine extra coolies and a second shikara to tow, and advanced on Srinagar. Hesketh’s boat, being the lighter, kept well ahead (here let me note that “bow” in that boat is quite the prettiest girl we have seen in Kashmir, and the minx knows it!), but we had good men, and worked along slowly and steadily up the main river, the side canals being all choked by broken bridges and such like.

We crept past the Amira Kadal, or first bridge, about two o’clock, and tied up for lunch, reveling in the most perfect pears, peaches, and walnuts. As a rule the Kashmir fruit is disappointing; abundant and cheap certainly, but not by any means of first-rate quality. Strawberries, cherries, apricots, melons, and grapes might all be far better if properly cultivated, and scientifically improved from European stock. The pears alone defy criticism, and the apples, I am told, are excellent also.

He made them travel on all-fours in the risky places. Fathers were very dictatorial in those days, and there was nobody about to make them consider their dignity.

One can imagine the scene. Ararat, a muddy pyramid dotted here and there with olive trees—curious, by the way, to find olives so high!—in the receding waters the vagrant raven cheerfully picking out the eye of a defunct pterodactyl.

The heavy clouds rolling off the sodden world—they must have indeed been heavy clouds, nimbus of the first water—as they had raised the world’s water-level 250 feet per day during “the flood” . . . surely a record output!

The primeval family party, sadly poking about along the expanding margin of the world, noting how Abel Brown’s tall chimney was beginning to show, and how Cain Jones’ wigwam was clean gone. Mrs. Shem said she knew it would, the mortar work had been so terribly scamped.

And Naboth Robinson’s vineyard—well, it was in a pretty mess, to be sure, and serve him right, for Mrs. Noah had frequently offered him two of her (second) best milch mammoths for it; yet he had held on to his nasty sour grapes, like the mean old cur-mudgeon that he was.

And now Hammy must set to work and tidy it up; and oh! What lots of nice manure was floating about, all for nothing the cartload. . . And so the primeval family felt better, and went back to the ark tea, feeling almost cheerful, but rather lonesome.

Fortunately this great flood did little injury to life or limb. A certain amount of destruction of crops and other property was inevitable, but on the whole the loss was not so great as was at one time feared, and much was saved that at first seemed irreparable.

A well-known lady artist came near to giving the note of tragedy to the British community, and losing the number of her mess (to use a nautical, and therefore appropriate expression) by reason of a big willow tree, beneath whose shady boughs she had moored her floating studio. This hapless tree, having all its sustenance swept from beneath by the greedy water, came down with a crash in the night upon the confiding house-boat, and all but swamped it.

The cook-boat, occupied as usual by a pair of prolific Mangis and their large small family, was saved by the proverbial “acid drop”—the children crawling out somehow or anyhow from among the branches of the fallen tree.

The fair artist, having with shrieks invoked the aid of a neighbour, he promptly descended from his roof or other temporary camp, and helped her with basins and chatties to bale out the half-swamped boat. The lady is now safely moored to the mudbank on the other side of the river where willow trees do not grow.

The whole bund is in a very unsafe state: it was raised three feet after the last flood, but its width was not increased correspondingly. Now that the water has fallen, great fissures and subsidences have appeared and in many places large portions of the bank have fallen away, carrying big trees with them.