There was a time when watches would fascinate people. Not anymore. Defying change, an octogenarian shopkeeper is trying his bit to keep the hands of clock ticking in Shehr-e-Khaas. Sehar Qazi tells his story

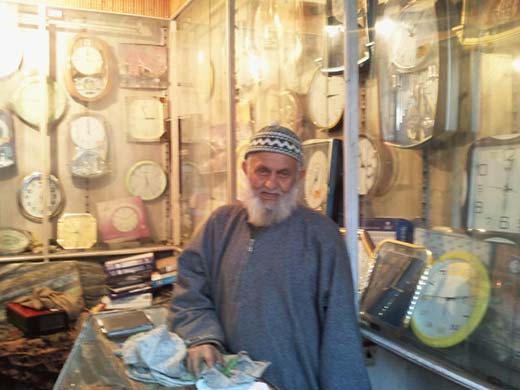

Ghulam Nabi Sheikh, who is in his early 80s, wearing a grey pheran with black dots, white and dark green knitted prayer cap and old shoes, is sitting behind a small glass-topped counter. He doesn’t recall his exact age. But a look at his wrinkled visage, his free flowing grey beard, and his single decaying tooth takes you back to some eight decade. Or perhaps more!

He sells watches. Of all sizes, colours, makes that used to fascinate passerby’s visiting Jamia Masjid in the heart of Srinagar.

With modern technology fast making watches and the people selling them irrelevant Sheikh is trying to fight the odds. He is perhaps one of the last few remaining timekeepers in Kashmir’s oldest market place called Sheh-e-Khaas.

But as it goes, every timekeeper has a story to tell. And Sheikh’s story starts from the days when kids were dragged to schools by policemen and not accompanied by their parents!

“I have studied till 6th standard at Jabrie Sakool (forced schools),” recalls Sheikh while dusting watches hanging behind him.

Jabrie Schools were introduced by Maharaja Hari Singh, the last autocratic ruler who inherited Kashmir from his great grandfather Gulab Singh. Maharajas are remembered by Kashmiris for their cruelty.

“These schools were exclusive for Muslims. Police used to come to our homes and take us to school. My school was at Kraleyar Rainawari,” says Sheikh with a smile while recalling his school days.

Another reason for Muslims skipping schools was that only educated Hindu’s were preferred for government jobs. “I wish I would have studied till 10th…,” he stops being thoughtful and smiles again.

Ghulam Nabi struggles with his faded memory while recalling his childhood. He remembers the games played and some of his close friends, “Age! I don’t remember much now,” he says smiling. “I used to play Sanzlanges (Hopscotch) and Qabeth (Kabaddi) with my friends in school. All my close friends, Ghulam Mohd Ahangar, Ghulam Rasool, Ghulam Ahmad Zargar have died. They lived at Hazoribazar (Khar Mohalla)”, he says with the change in his mood.

Recalling the tribal war by Pakistani backed raiders in Kashmir, he said, “We used to climb rooftops to watch them fighting. It was Kabel Jung.”

“Badamwari – mazeh ous yewan (we used to enjoy). I and my friends used to go to Badamwari. The place was known as Gearh Bagh. Bakshi saeb (PM of Kashmir), used to come there and Ame Suf (Ama Sufi, one of the known Kashmiri singer), would fill the air with his music. We used to play, and eat gearh (sweet chestnut),” recalls Sheikh.

“Hakkhas ous tuthe mazeh asaan (Collard greens had such a good taste), na roud tem banaven wael, na roud tem sean, (neither such food is available nor such cooks exist now). We used to purchase Pachin (Heron) from Habba Kadal, but now it is not available there,” rues Sheikh as he finds everything tasteless and adulterated.

Sheikh hails from Mughal Mohalla Rainawari in Srinagar. Interestingly his old house resembles the house of Maqbool Bhat – JKLF founder who was hanged inside Delhi’s Tihar jail in 1984.

Rain has stopped and day seems bright. Weather and seasons decide the time to open the shop. It remains closed in rain and snow.

Reluctantly, he speaks in a soft tone which disappears in the sound of vehicles passing by his shop. Walls clocks are dangling in the display glass. These clocks are of different shapes and colours. None of the clock shows the same time. The golden coloured ladies wrist watches, six digital watches, brown spectacle and two rust driven boxes lay inside the glass topped counter. The two boxes are filled with the lithium button sized batteries and repair tools.

“I started this shop 30 years back, you calculate the year yourself now!” says Sheikh in a soft tone accompanied with a smile. His decayed tooth is visible with every smile.

Sheikh has been witness to changes that happened over the years both in terms of people’s preferences and style viz-a-viz watches. “In the past watches had keys but now they work on cells. Since technology took over wearing a watch is out of fashion now. People mostly come for wall clocks now. And that too fancy ones,” recalls Sheikh.

In the good old days, Sheikh recalls that possessing a wrist watch or a wall clock was a big thing. “Only a blessed few could afford to own these objects of desire,” says Sheikh. “But now everyone has a clock in his house.”

After leaving his studies mid-way Sheikh started working with his father, Ghulam Mohammad Sheikh. “I used to get wool for the pashmina shawls from Navidyar. Later I joined National Silk Industry as an artisan,” says Shiekh.

During that time National Silk Industry was located at Dalgate under the supervision of G M Bhat. After working there for around 15 years, Sheikh started selling watches. “Those were the times when people would throng my shop for a glimpse of these beautiful time machines. But I guess my time is gone now,” he says looking at the people walking outside.

Despite the change and dwindling footfall of customers at his shop, Sheikh is a content man. “My son has done B.Com and my daughters have done MA,” he says proudly with sudden shine that brighten his face.

Father of a son and two daughters, Sheikh claims to be the only person of his age in the Mughal Mohalla area who had allowed his daughters to continue their studies. “In our area there are many rich people but their daughters are not as educated as mine,” says Sheikh proudly.

Sheikh’s elder daughter is a teacher and the yougner one is manager at J&K Bank.

With his trembling hands Sheikh continues to repair watches and replace their batteries, surprisingly without using spectacles. Pointing towards the glass counter in front of him, he says, “Nowadays I have more girls visiting my shop for fancy and stylish watches. I am slowly trying to adopt myself to this change.”

While most of the shops selling watches in the vicinity closed Shiekh is happy to at least have 5 to 6 costumers daily.

Reminiscing about the past, he clearly remembers about the watches people mostly purchased then. “People were simply crazy about HMT watches. There was a watch making factory in Kashmir but the director was killed during Tehreek,” he said, not being sure about the year.

When Kashmir Life requested him for a photograph, “beh yemai pagah coat pant lagith, atae tolzi” (I will come wearing coat and pant tomorrow, then click my picture) and he stands with a smile.