Weighed and weathered down in wait for their disappeared sons, many fathers have faded, while those surviving are continuing their struggle in the face of their eternal wait. Bilal Handoo reports the plight of fathers fading for their disappeared sons

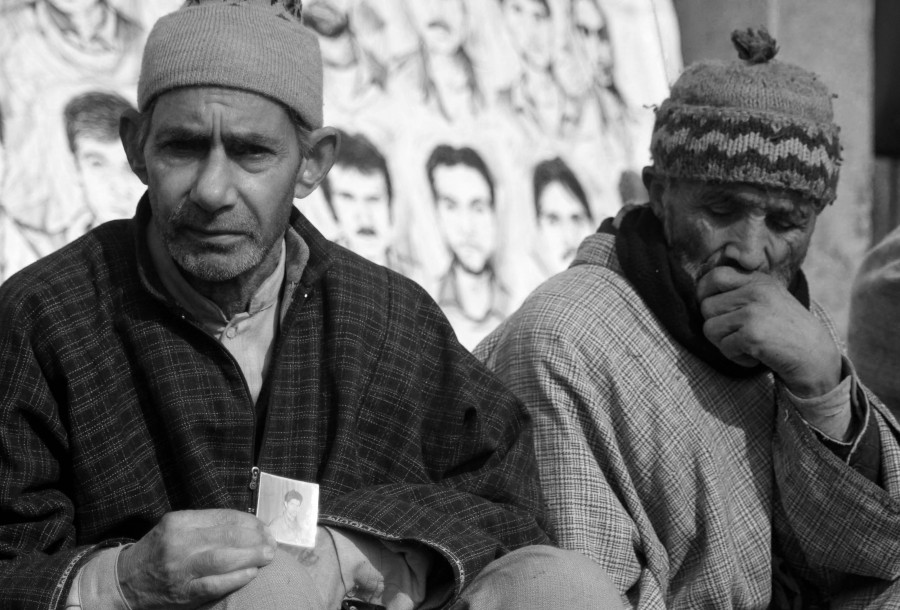

(Noor Mohammad from Pattan is waiting for his son since 2003. Pic: Durdana Bhat)

Years of agonised wait was about to end in a most disturbing manner. He was lying on his deathbed, breathing heavily, mumbling his son’s name. The longing for his son whom he last saw on April 27, 1996 was still supreme.

Eighteen years had passed since. His parched face, fragile figure and feeble strength reflect the plight of those fathers who are slowly fading (without creating a stir in the society they live in) in anticipation to have a reunion with their disappeared sons. But to their woes, their wait doesn’t wane.

That night in January 2014, he saw his disappeared son, Shabir Hussain Bhat, in his dream. The father and son hugged each other, wept at length. It was the most cherished and prized sight for a father. In his dream, his son (who was only 18 at the time of his disappearance) told him: “Father, please be patient. Allah will surely settle the scores.”

The next day, the father conveyed his dream to his elder son Shafiq Ahmad Bhat and other family members. And within no time, the Bhat house of Srinagar’s Chattabal was under an intense mourning spell. And soon, the fading father faded forever!

Eleven months later…

The world was observing World Human Rights day. The year 2014 was described as the “most horrific year for human rights violations”. Unaware of the slogan, parents of disappeared persons had started pooling inside Srinagar’s Pratap Park for a customary sit-in protest on every 10th of the month. It was December 10 and the sun was out to light up the overcast faces of parents of disappeared persons amid palpable chill. One by one, they all walked inside the park and quietly picked up posters printed with poignant query: “MISSING. Laapat’ta. Where are our dear ones?”

Soon, a cry broke out. An aged mother started crying loud for her son who is missing since late nineties. Others followed. While mothers, who were sitting in the front rows cried their hearts out, the last row occupied by the brooding fathers was disturbingly quiet. Among them was Shafiq Ahmad Bhat of Chattabal who had stepped into the shoes of his late father. He was holding a poster in his hand that read: “Enforced Disappearance is a crime against humanity.”

He wore tired eyes and unkempt face of somebody who had apparently lost all his hopes to the ‘prevailing indifference’ for families like his, in a society they live in.

Meanwhile, the park was getting crowded. Clicks of cameras, sound bites of parents and frequent wailing started building up the sombre mood around. Amid all this, Shafiq was reluctant to unfold his grief. “For god’s sake,” he yelled, “what shall I narrate? Do you want me to recount, how our life was devastated?”

A silence amid distressing sounds ensued.

“To recount the harrowing history requires extraordinary spine,” an anonymous adage flashed through memories. By recounting their share of pain repeatedly, parents of disappeared persons have indeed shown an “extraordinary spine” in the face of their crushing tragedy.

Shafiq stared hard at unfolding events in the park before preparing himself to narrate the “nightmare” of his family. His younger brother Shabir Ahmad Bhat was a responsible son at the age of 18. He was into carpet weaving business and was supporting his family. On April 27, 1996, Shabir, a son of artisan went to visit his business friend in Srinagar’s HMT. He had no hunch that nearby Shariefabad army camp was about to doom his family. “One army major, Thakur Ramaya, of the camp picked him [Shabir] up,” recalled Shafiq, a painter rendered roofless in September floods. “And since then, there is no clue of him.”

What followed for the family was a typical traumatic struggle akin to thousands of such families. Vicious visits to Kot Bhalwal, Tihar, Jodhpur, Rajasthan and other places followed. “Most of the doors that we knocked were slammed shut on our faces,” Shafiq said. “We were shooed away, saying, ‘Get off from here, you terrorists!’ ”

It was Shabir’s grandmother who first came out and joined Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons. Her struggle ended after she breathed her last in early 2000. After that, Shabir’s father Mohammad Hussain Bhat joined the caravan of thousands who are frantically searching their dear ones. But year after year, the caravan is losing its members to death angle. “Not many are left now,” Shafiq said who lost his father in January 2014.

The rush was building inside the park with each passing moment. Camerapersons kept capturing sullen, sad and sobbing moods at display. And those who were quiet let their posters did all the talking: “Implement court orders, prosecute the guilty.”

In the middle of the last row, a father from Beerwah Budgam, Ali Mohammad looked like a wretched man. Since 1993, his son Bashir Ahmad is missing. “My 20-year-old son stepped outside and disappeared,” said Ali, amid sobs. “And that’s it.” Twenty one years after, Ali is still searching his missing son.

While he was still in the middle of his tragedy, another struck. Eleven years after his son’s disappearance, the forces stationed in his village, Dasan, “conspired” in connivance with local mukhbirs or informers and took his second son Mohammad Yousuf away. It was on August 11, 2004.

Mukhbirs along with army had visited his home in dark. They took Yousuf away on pretext of seeking direction. But he never returned. The next day, his body was found in nearby Watterpora.

(He is fading in anticipation to have a reunion with his son. Pic: Durdana Bhat)

Mourning, an extreme mourning followed. Later what rubbed salt on Ali’s wounds was the “fabricated” report prepared by the CID that maintained: “Ali was a Pak trainee!”

But the local police station contradicted the report admitting: Ali’s slain son was innocent. “But was that enough to bring him back?” Ali asked. “My son’s only sin was that he had a typical Afghani appearance and dress code. And that gave them enough ground to kill him!”

This farmer of Beerwah is also taking care of his sons’ children, besides continuing his struggle. While his disappeared son left behind a son, his slain son Yousuf left behind two daughters. With his prime well past him, there is a strange spark in Ali to fight for justice, eluding him so far. Ali’s eyes shone before he said: “Till I am alive, I would never rest in peace and will continue my struggle.”

As the time was fast heading to noon, the clamour created by cries peaked up in the park. Unfazed by all this, a father from south Kashmir’s Bijbehara town appeared lost in his own thoughts. His name was Abdul Rahim Mir, who along with his aged wife is looking for their son, Bashir Ahmad Mir (a class 9 student) since 1994.

Two decades ago, some masked men appeared at his doorsteps who insisted to talk to Bashir. “As I followed my son,” Rahim recalled, tightening his facial expressions, “these men slammed my head with guns.” The moment he was back to his senses, he realised his world was devastated.

A routine fruitless chase followed without interruption for one complete year. “During that period, I and my wife didn’t step inside home,” he said, inching close to break-down.

What added to his desolation was his other two sons’ decision to live separately. “Though my sons had their own reasons for that, but it badly disturbed us [he and his wife],” Rahim said. Since then, the old couple from south Kashmir are putting up alone.

Over the years, the search for his son has faded him to an extent that he has now started questioning his own self and struggle. “Do you think anything will ever happen to our case?” he asked and turned his face back to the front.

Another visibly broken father present in the park was Noor Mohammad Bhat of Ari Mohalla, Pattan. His son is yet to return home since June 22, 2003. Mohammad Ashraf, his son was 21 when one Fayaz Ikhwani of his village cut his stride short in Batamaloo bus stand and took him away. “Ashraf was with his mother at that time,” Noor recalled. “Before taking Ashraf away, Fayaz promised his mother that he would bring him back home by 4 PM that day.”

That day as clock struck 4, the Ikhwani rang up the family. “Look, your son is safe. He will stay with me for a night. And, tomorrow I will drop him home myself,” the Ikhwani assured the mother. “Alright, but let me talk to my son,” the mother pleaded. But the phone had gone dead without fulfilling the mother’s wish. “And since then, there is no clue of our son,” Noor continued. “In fact, the Ikhwani himself is missing since then!”

The sun, meanwhile, had gone into hiding. A piercing chill became palpable. In these frigid times, the ominous warmth for these parents weathering in wait came through conversation. At least, once in a month they converge inside the naked park for the socialisation they would have never wished for themselves years before tragedy struck them. Amid all this, Shafiq Bhat of Chattabal kept staring at the poster to his left: “No one shall be subjected to Enforced Disappearance!”