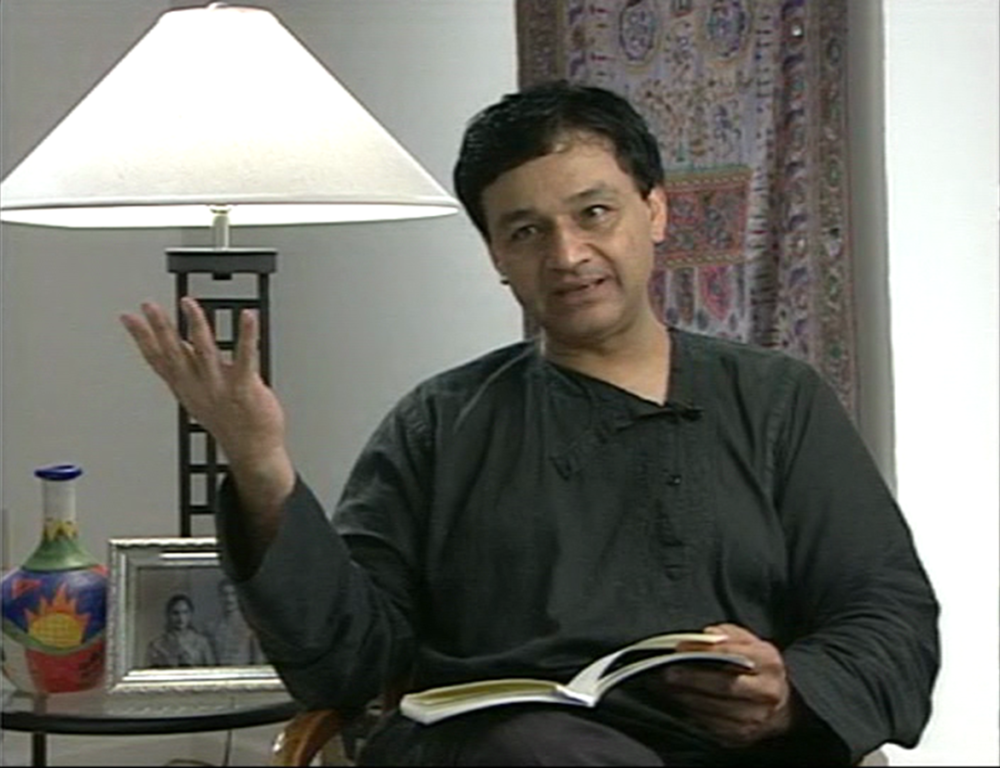

Poet Agha Shahid Ali (February 4, 1949 to December 8, 2001) eventually became Kashmir’s identity in the English literature. On his fifteenth death anniversary, Prof G R Malik, the former head of English department in the University of Kashmir, helps understand the essence of Agha’s art and pain

Kashmir is Agha Shahid Ali’s alter ego, his first and last love and, consequently, the source of inspiration for his finest work. This is why he emerged as a potent voice in poetry with The Country Without a Post Office.

Although several volumes of verse (Bone-Sculpture, In Memory of Begum Akhtar, The Half-inch Himalayas, A Walk Through the Yellow Pages and A Nostalgist’s Map of America, not to speak of his translations of Faiz Ahmad Faiz), of unquestionable literary worth had preceded it, it was The Country Without a Post Office and, in some ways its sequel, Rooms Are Never Finished that finally established his authority as a modern poet.

In his early youth, circumstances took him away from his homeland and this separation seems to have inflicted a wound on his psyche. His poetic imagination nursed the wound as a source of inspiration but the sense of separation turned to burning anguish as the poet saw his motherland in deep trouble and yelled Faiz-like:

Meray watan teray daman-i tar tar ki khair

(My homeland, hail to thy skirt torn to shreds).

This anguish was extremely intensified with the loss of the poet’s mother as mother and motherland merged to assume a single identity giving birth to a still, sad and, therefore, highly powerful and penetrating poetry. This poetic power grips us from the very start of The Country Without a Post Office. The title itself is a complete poem. Post Office symbolizes address, identity, and if you have no post office, you have no identity. What is there more to say? But the heartache is too great for a single stroke. As you turn to the next page, you come across another master stroke. This time it is the epigraph, the choice of till epigraph from Surah al-Qamar of the Quran:

Iqtarabah al-saut-u wainshaqal-qamar

(The Hour draws nigh and the moon is rent asunder.)

The epigraph points to the horror that underlies the poem – the horror of doomsday. Eliot’s first epigraph for The Waste Land was, “the horror, the horror” which he had borrowed from Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness.

We enter Shahid’s wasteland on this note of horror. It is his motherland which has been laid waste equally by its own and the alien hands. Shahid aptly quotes Tacitus:

“They make a desolation and call it peace“.

‘When you leave home in the morning, you never know you will return.’

Prejudiced minds view it through coloured glasses and misconstrue it, indicting one criminal and absolving the other; sympathizing with one victim and ignoring the other. It is only the sensitive and broad-minded poet who feels the human pain and suffering in the marrow of his bones and weeps:

I see men coming out of those

Abodes of snow with gods asleep

Like children in their arms.

They (the Kashmiri Pandits) leave with their gods for havens of fractured peace, haunted by heart-piercing nostalgia of the lost paradise. And those whom they have left behind in the erstwhile paradise, suffer the torments of one thousand hells and yet they breathe:

Humankind can bear anything.

Bersar-e-Awlad-Adam Herchiayed Biguzard

In this paradise no one is safe. A visitor like Hans Christain Ostro is swallowed by the abyss of horror and makes Shahid brood and lament the loss of the most priceless quality of the Kashmiri genius – its warm humanity and endless hospitality, its freedom from narrow prejudice and discrimination on grounds of creed and colour. Of this the poet is a faithful heir.

Amitav Gosh, in his book, The Imam and the Indian, recalling one of his last meetings with the poet, writes:

“This was a time when his illness had forced him into spending long periods in bed. He was lying prone on his back, shielding his eyes with, his fingers. Suddenly he broke off and reached for my hand. “I wish all this had not happened,” he said. “This dividing of the country, the divisions between people – Hindu, Muslim, Muslim, Hindu, you can’t imagine how much I hate it. It makes me sick. What I say is: why can’t you be happy with the cuisines, and the clothes and the music and all these wonderful things? He paused and added softly, “At least here we have been able to make a space where we can all come together because of the good things.”

(Quoted in Memorial Volume-III)

Will the Kashmiri genius come back to its lost path? Will the perfect day ever dawn again of which Shahid dreams:

On this perfect day, perfect for forgetting God,

Why are they Hindu or Muslim, Gentile or Jew,

Shouting again some godforsaken word of God.

That is agonizing lamentation. Yet it is not lamentation raw and half-baked for it is poetry. The poet is in possession of the aesthetic distances required to convert heart-ache into poetry. With the weapon of language, he defies and subjugates all despair. Appreciating this, Yerra Sugarman, wrote to him on receiving his poem, Lenox Hill:

“You encouraged me with the courage of your words by the way they move, inside the fire and water of loss, a loss which I have barely begun to grapple. You and your poetry roused me to the hope that I will pull myself out of the quagmire of bewilderment and despair in which I’d been since my mother’s passing. You reminded me, that lovely afternoon that I must try to defy with language the universe’s attempt to conceal her from me.”

(Quoted in Memorial Volume-55)

This aesthetic distance is the source of his remarkable poetic technique which characterizes all his poetic output and which, I believe, will stand out in the end as his defining feature, his forte as a poet. The hallmark of this poetic technique, apart from its metaphorical use of language and a subtle ironical infrastructure (the Sineqaaaon of any poetry worth the name), is its exquisite formal finish and deft and masterly manipulation of words. The pyramid-shaped ordering of word in the ostensibly simple dedication of The Country Without a Post Office is very significant from this point of view. It looks like the inaugural stroke of a musical symphony, complete in itself, like a finished poem:

For My Mother – Sufia –

The Bravest of Them –

& of us

All

Shahid’s handling of the complex verse-forms like the sestina, the canzone and the ghazal indicate his instinctive pull towards serious engagement with ‘form’. Lenox Hill, his moving elegy on the death of his mother, would alone be enough to testify to his verbal virtuosity and his masterly manipulation of such a strict and challenging form as the canzone. In his letter to the poet, Yerra Sugarman rightly assesses it:

“… how passionately the bone-close emotions are sustained and buttressed by the ardour and relish of craft throughout. So seamless is your canzone, it is as though the poem had chosen the form for itself….. ‘Lenox Hill’ is a tree of grief, a web of branched entwining pain flowing through veins of time, the veins of every living being.

(Memorial Volume 56)

To take on the immensely complex and formally so demanding a genre as the ghazal in English is yet another evidence of Shahid’s virtuosity, though in his handling of the form, one cannot help feel that a meaningful maintenance of quafiah and radif generally eludes him as can be seen in the ghazals ending with the refrains, In Arabic, Even the rain and In real time.

Having said that, however, it is apt to bear in mind that it is almost next to impossible to balance the signification of the ghazal with its rigid formal scheme in English. Perhaps this is the reason why Shahid usually avoided Faiz’s ghazals while translating him into English and chose to translate his poem (nazms) instead and in their rendering too, he took maximum possible liberties. As a translator, therefore, he is more in line with tradition of Edward Fitzgerald than with that of Nicholson and Arberry. Read, for instance, his beautiful renderings of Faiz’s poem, Yad (Memory) and Ghalib’s ghazal, SabKahan Kuch Lala-o-Gul Mein Numayan Hogayeen in Rooms are Never Finished, one who has not read the original will enjoy these renderings immensely for they an genuine poetry, exuding charm and brilliance, but one who has the original in mind will halt and ask questions.

Faiz’s lines:

Door Ufuq Par Chamakti Hui Qatrah Qatrah

Gir Rahi Hai Teri Dildar Nazr Ki Shabnam

are translated as:

…And farther,

Drop by drop, beyond the horizon shines the dew of your lit face.

And Ghalib’s verse:

Yad Then Hum Ko Bhi Ranga-Rang Bazam Araiean Lekin

Lekin Ab Naqsh-o-Nigar-e-Taq-e-Nasiyan Hogayeen

is rendered as:

Time ago I too could recall those moon-lit nights,

Wine on the Saqui’s roof –

Bt Time’s shelved them now in its niche,

In Memory’s dim places.

Marvelous poetry indeed, but like Fitzgerald’s Omar Khayyam, it is Shahid’s Faiz and Shahid’s Ghalib. For the sake of balance and fairness one must did immediately that when such translation goes as near as it is impossible for a poetic rendering to the original, it touches the very climax of creative brilliance. See, for example, the following two extracts:

Sab Kahan Kuch Lala-o-Gul Mein Numayan Hogayeen

Zkhak Mein Kya Sooratan Houngee Ki Pinhaan Hogayeen

Not all, only a few –

disguised as Tulips, as roses –

return from ashes.

What possibilities

Has the earth for ever

covered, what faces

(Shahid’s translation)

Dasht-e-Tanhayee Mein Ay Jan-e-Jehan Larzaan Hai

Teri Awaaz Kay Saye, Teray Hountoon Kee Saraab

(Faiz)

Desolation’s desert, I am here with shadows

Of your voice, your lips as mirage, now trembling.

Grass and dust of distances have let this desert bloom with your roses.

(Shahid’s translation)

Such beauty as we witness here also sparkles through Shahid’s charming translation, trans-creation to be precise of Mohmoud Darwish’s Arabic poems, Eleven stars over Andalusia.

One vital aspect of Shahid’s poetic technique is that it comprehends and assimilates literary influences in the most organic manner. Here he reminds us again and again of T S Eliot who was the subject of his doctoral dissertation. Like Eliot, he makes use of all literature known to him as grist to the mill of his creative imagination.

Incidentally, the poem A Pastroal, like many other later poems, makes skilful us of Eliot’s Burnt Norton, reverberating with deliberate echoes of the poem through arresting phrases picked up from the poem, through its rhythms and through the general movement of the verse although in place of a mystical experience, it communicates a harrowing tale of death and ruination but not without looking forward to a secular redemption. Nor is this comparison with Eliot exhausted here.

Shahid’s poetic technique, if not the content of his poetry, exhibits an all-pervasive influence of Eliot. The dramatic quality, the presence of a listener, the colloquial tone, the conscious and not-so-conscious echoes of the earlier poets, the quotations from diverse sources all show his essential kinship to Eliot. Like him too he merges together many an entity to put across something that is of universal validity.

Muhrram in Srinagar in The Country Without a Post Office and Zainab’s Lament in Damascus in Rooms Are Never Finished exemplify this trait most exquisitely. In the latter poem, Shahid’s art touches new heights; Zainab’s lament is at once a lament for Husain, for Shahid’s mother and for Kashmir with Shahid’s own identity merging into that of Zainab. This merging of identities of the poet and Zainab, and mother and motherland constitutes the leit-motif of the larger part of Rooms Are Never Finished.

The collection opens with an account of the martyrdom of Husain, a pithy and comprehensive poem in prose. Jesus, with his disciples, is shown as passing through the plain of Karbala. Pointing to the spot where, centuries later, Husain is to fall a martyr, Jesus breaks down and waters the desert sand with tears.

This reminds us of Milton’s Paradise Lost (Book XI) where Adam sheds tears for the destruction of his progeny in the deluge of Noah. Shahid’s bridge-building across cultures, of which his translations and the introduction of the form of ghazal in a big way into English are glaring instances, thus works subtly at deeper inter-textual levels.

Shahid is a bridge-builder no doubt, but can one go so far as Amitav Gosh does when he describes him as an heir to the tradition of Rumi and Kabir? Rumi and Kabir are signposts of a mystical tradition which Agha Shahid Ali neither did nor perhaps would have professed.

Notwithstanding the fact that he had consciously and unconsciously imbibed the humanitarian, hospitable and to tolerant outlook of Kashmir which springs, to a large extent, from our mystical underpinnings, his vision ultimately remains a secular vision and his tradition, the tradition of modern English poetry represented by T S Eliot (technique-wise) and such modern American poets as James Merrill. Into this tradition, he successfully interweaves elements from the tradition of Urdu lyrical poetry especially that of Ghalib and Faiz together with influences from other Asian and European literature available to him in translation. Within this domain he achieved a depth and grandeur whose dimensions will unfold gradually with the passage of time for, like all extraordinary poets, he was ahead of his time and we must entrust his final assessment; to the future.

(The essay first appeared in Sheeraza, the English quarterly journal of culture and literature in 2012 fall.)