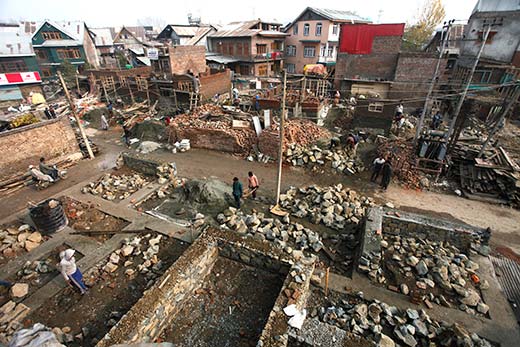

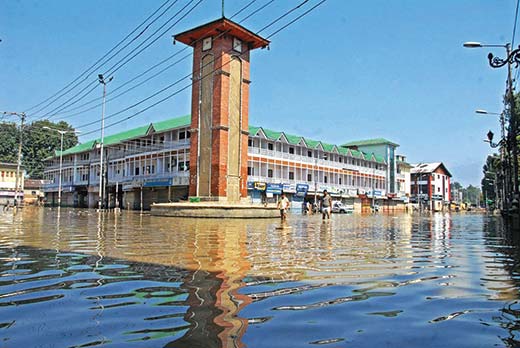

Most of the skimpy infrastructure, part of the trade and best housing enclaves were decimated by September 2014 floods. After Omar Abdullah lost his plot to the deluge paving way for PDP to take over the ruined vale, Mufti Sayeed is still unsure about joining Kashmir history’s big league of rulers who attempted rebuilding the city, R S Gull explores

Pic: Bilal Bahadur

It required a real effort to trace Omar Abdullah’s government after Jhelum’s historic high discharge triggered massive urban floods in September 2014. A chopper parked in its lawns, a towering military wireless post erected near its main entrance and a handful of visibly upset people getting in and out of the tents pitched on the greens: the Gothic monster that Hari Singh had built for his queen – only to beinhabited temporarily by his court singer MalikaPukhraj till the monarch fled- the secluded HariNiwas Palace exhibited a rodent’s silence. Looking akin to a safe house where a battle-bruised General was recuperating, it was here the government regrouped and ‘retook’ the secretariat almost a fortnight later.

Floods incapacitated options as tens of thousands wandered around for food and shelter. Only 300, mostly in Jammu, died and not more than 25 were injured. A total of 2,61,361 structures were impacted – 21000 of them actually washed away. Omar’s government indicated a will to do but lacked ideas. Its defeat in LokSabha elections had demoralized the party and alleged inaction over flood management only added to its governance deficit. Surveys for assessing the damage were carried out but the process was faulty. Omar paid for that.

Omar, however, is surely not the first Kashmir ruler who was caught inundated. History is replete with instances of kings getting trapped in floods.

During Sultan Shihab-ud-Din’s reign a “devastating flood” inundated Srinagar in 1360. “…there was not a tree, not a boundary mark, not a bridge, not a house that stood in the way of the inundation, which it did not destroy,” recorded Jonaraja, the Kings of Kashmira author. The king took refuge in the hill fort.

Zain-ul-Abideen, Kashmir’s famous Budshah, could not escape a major flood in 1462. It was so fierce that Jonaraja recorded “…the buildings in the city drowned themselves in water as if to avoid the sight of the distress of those who had raised them.”

Even the Mughal Emperor Shah Jehan, the builder of most of the gardens that were ‘sold’ as Firdous Baroie Zameen to tourists for the last four centuries, was also caught in 1638 floods in Srinagar that devastated most of the city. The flood later led to a famine that consumed thousands of lives.

What made all these rulers to still get their space in history was their response to the calamities they landed in. Budshah built his new city of Srinagar at the foot of the Hariparbat hill that still exists as Naushahar. He repaired protective embankments that had originally been raised by Suyya in ninth century, and deepened the river bed at Baramulla for a speedy discharge.

Shihabuddin built a ‘beautiful’ town, Lakshmipura, again on Hariparbat foothills, immortalizing his queen Lakshmi. It is a different story, though, that her sister’s daughter Lassa enticed the king in the meanwhile and Lakshmi had to be deported along with her two sons from the city founded in her name.

Inherent problems in NC-Congress coalition apart, Omar might have attempted to do his bit after the September 2014 floods literally washed away his government. But by then PDP had successfully created the debate: ‘a government that failed in crisis cannot sit over the judgment over follow up’. Omar made no effort to retrieve his plot. In post haste, the follow up to crisis was crudely managed and had inherent flaws which, the new government says, may take some more time for course correction.

A new government is in place since March. Nothing much has changed in where Omar had left. In the immediate response to floods, every agency had chipped in and created a chaotic response. Under SDRF norms J&K was entitled to Rs 2926.11 crore of which Rs 1566 crore were for temporary restorations. “The High Level Committee approved Rs 1602.56 crore of which Rs 500 crore stand earmarked for the IAF leaving a balance of Rs 1102.56 crore only,” Law and Relief and Rehabilitation Minister Basharat Bukhari told the assembly in March.

Funding the restoration of public infrastructure apart, relief is coming from different sources: some money is coming from SDRF, some from Chief Minister’s Relief Fund as Prime Minister directly credits his relief to the flood affected population. “I think, by now, total outgo should be upward of Rs 1200 crore,” state’s planning commissioner B R Sharma said. “But a lot many things are in the pipeline.” Top officials do not disagree that insurance agencies have dished out almost the same amount with Bajaj Allianz taking the maximum hit.

Now World Bank is the focus of attention. Soft loan by the bank to the central government could come as a grant to J&K. But how it is to be managed is the real big issue. The Bank has already committed Rs 1500 crore in the first instance. It has already completed its surveys and assessed the needs of J&K state at Rs 21000 crore. “It requires a lot of negotiations to see it happening,” Sharma said. “But let it start first.” Interestingly, central government presumes the loss to be not more than Rs. 11000 crores.

Post-flood policy making is literally caught on the wrong foot. The overall losses were assessed to be Rs 100,000 crore plus. Post-haste Omar government sent a memorandum to Delhi seeking Rs 43960 crore, over and above the SDRF-NDRF framework. It was based on the demands that various civil society groups made. It even included Rs 8000 crore that the state government required to manage its resource gap, government sources said.

“The memorandum is there in the MHA and nobody seems to have even touched it so far,” Finance Minister Dr Haseeb Drabu said. In his budget proposals Drabu had disputed its design and termed it ‘asset-centric’ ignoring the flood-impacted population. “As of now it is the Rapid Need Assessment teams of the World Bank whose report offers the basis for possible funding for rebuilding and restoration.”

The government still does not know how it will jack up a third-party assessment to make it closer to Rs 44,000 crore. One idea, Sharma points out, is to manage part of the requirements through open market credit especially if Delhi agrees to the idea that all the advances in the state for some time should remain as priority sector lending. The government, in that case, will have to fund the interest subvention of the credit off-take.

In his budget proposals Dr Drabu was clear on one thing: “We will not be able to bankroll the entire rehabilitation on our own or even in partnership with the Centre but we will have to find ways and means of doing so.That is what the government is all about.”

Right now, he is less interested in the size of funds and excited about quality of grant and the utilization process. “At the end of the day, it is the long term sustainability of the expenditure you make, infrastructure you create and capacity you build, that matters” Drabu said. “Assuming that every coin that was lost to floods is compensated, the issue is how well we can spend it to affect a visible socio-economic change.”

It seems the government expects Delhi’s help in rebuilding public infrastructure; evolve a joint state-centre approach for rebuilding private assets and use the open market lending to manage the business liabilities created by the devastation. But will this script help Srinagar undo the devastation it witnessed in floods and upgrade itself as a modern city or, as they say, ‘the Rs. 1500 crore smart city’?

Srinagar, one of the oldest cities in subcontinent, has suffered for ages. Cutting across faiths, rulers have been unfair to it ever since Ashoka supposedly built Srinagari with Pandrethan as its capital in 250 BC. All the successive kings ruled Kashmir from there for next 850 years. And then Hindu kings Praverasen-I, Praverasen-II built their own ‘mohalla cities’ to host their capitals.

Then, capital shifting became the new norm. An inebriated Lalitadatiya (724 CE–760 CE) in fact wanted destruction of the city after he took his capital to Parihaspura. Capital was moved to Jayapura near Sumbal by Jayapida, to Awantipore by Awantivarman (855-883 A.D), to Samkaranpura (Pattan) by Shankaravarman (883-902), to Kaniskapora (now Kanispora), to Juskapura (now Zakura) and to Hushkapura (now Ushkar) by various other kings. Barring a few temples of those times, nothing much is available now from the Hindu era.

However, infrastructure that came up during and after Muslim rule is still traceable. Ever since Rinchana built Rinchapura, every new Sultan would traditionally set up a new locality – Allaudin Pora, Qutubuddin Pora, Zainakadal, Naushahar. During the reign of Sultan Hyder Shah, even Nowhatta was the capital. For a change, the Sultanate would call the city, the Shahr-e-Kashmir, the city of Kashmir. Much later in 1819, Sikhs rediscovered Srinagar.

Most of the heritage that Kashmir boasts of belongs to various rulers from different time eras. Jamia Masjid was built by Sultans, Mughals built the Nagar Nagar (the massive wall surrounding the fort to house the military town) and laid almost all the gardens across Kashmir, Sheraghri Fort and the AmiraKadal (bridge) by Afghan king Amir Khan Jawansher (1770-76), Hari Parbat Fort by Atta Mohammad Khan Barakzai (1806-13) and most of the existing key infrastructure including the chest disease and SMHS hospitals came up during the last few decades of the exploitative Dogra rule. Jhelum Valley Cart road, the first ever road that Kashmir could boast of was completed in 1890. The first vehicle that wheeled into Baramulla, not Srinagar, on September 13, 1890 was when Pratap Singh drove on this road. Second major milestone on surface communication was on May 2, 1921 when Banihal Cart Road was opened for durbar move.

Development has remained a regular process but none of Kashmir’s post-partition rulers have any impressive record for building the infrastructure. While Bakhshi Ghulam Mohammad during his famously long and notoriously corrupt era built the key official infrastructure including the civil secretariat, Sheikh Abdullah set up the SKIMS and built the new Dargah Hazratbal complex. Their contributions to new housing enclaves proved disasters: Bakhshi’s Jawahar Nagar and Sheikh’s Bemina – both were decimated in 2014.

Successive governments skipped a course correction and instead built on the bad decision-making: critical infrastructure was taken to Bemina flood basin, the latest being two hospitals, and encouraged filling massive marshes around Srinagar from Soura to Budgam. After filling Nulla Mar and converting it into a business pace, building homes on water-bodies became the only way-out for city’s expansion.

Undoing losses of the past sounds impossible but reducing their impact is still an option. As the second flood threat loomed over Kashmir in latter March, Mufti effectively led the government creating an indelible impression. That readiness conveyed not only his sensitivity towards calamities but also indicated insecurities and nervousness. Mufti knows the costs floods entailed for his predecessor.

But that impression is gradually neutralizing as nothing much is happening on rebuilding and management front. While efforts are apparently afoot to manage the resources to fund the loss, nothing much is happening about what should be done to reduce the costs if the calamity revisits Kashmir living in a 55 year flood cycle.

There is no final decision if the state government is willing to have a new flood spill channel and if it is keen to improve the existing one. Not a single penny has gone into the purchase of dredging systems needed to de-silt the vital part between Wullar and Baramulla, a priority even during Dogra rule. “The silt is so massively clogging the riverbed that even a small shower shoots up the levels in Jhelum,” says an engineer. “I do not know what the planners are thinking?”

Pic: Bilal Bahadur

Street voices after the floods were suggestive of rudimentary shifts – the land use policy, the city’s expansion modes, the building structures and even architecture in certain flood-prone areas. People expected a ban on constructions in low lying areas especially in the marshes and open spaces close to water bodies. Those having better exposure were even hawking on a policy delinking governance from business and luxury from housing suggesting Srinagar may evolve like a modern city having a governance space separated from various business districts and new housing enclaves. The process of de-silting the major tributaries of Jhelum including the few channels passing through Srinagar is yet to take off!

“My government is committed to rehabilitate victims and it is the top priority,” Mufti told media on the day first of durbar’s reopening in Srinagar. “We have provided a token of compensation to uninsured marginal traders and destitute. The people who have suffered damage to their property and trade at a higher scale are also being compensated.”

If these are the priorities then Mufti is willingly giving away a slot that history has offered him. Compensating the losses is just a routine process. Making the new investment to change the fundamentals is something that history will record for future. Calamity, after all is not a crisis alone, it is an opportunity too.

Repelling Article 370 is the way forward for J&K. This would result in more private investment like the rest of the country and hence more jobs. Kashmir itself has a lot of potential in areas like Tourism and Hospitality. This will help in reducing the migration of Kashmiris to other part of the country for search of jobs and will also help employ the poor youth and take them away from militancy. The advantages are manifold.