Despite previous government’s promise to bring the perpetrators of 2010 summer killings to justice, the killers roam free. Muntaha Hafizi talks to one mother who has lost her son but not the hope for justice

Ask anybody about Omar and you will be greeted by blank faces and questionable expressions. But ask them about Shaheed Omar and immediately heads correspond with respect, and then a story follows, with each detail carefully put through the eyes of multiple witnesses.

Ask anybody about Omar and you will be greeted by blank faces and questionable expressions. But ask them about Shaheed Omar and immediately heads correspond with respect, and then a story follows, with each detail carefully put through the eyes of multiple witnesses.

Quickly, an old man points towards a shrine, few metres away from Soura Chowk in Srinagar. In his coarse voice, he directs to an address: “Just opposite Malik Sahib Shrine, a lane goes to Shaheed Omar’s house.”

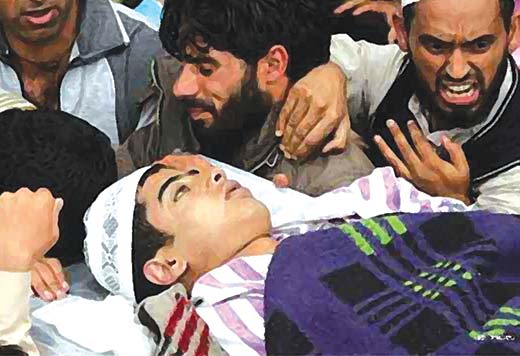

Omar Qayoom Bhat, 17, was one among the 127 people killed during summer 2010 agitation.

Through a light shaded side window, a tall and seemingly young woman peeps out introducing herself: Be chas Shaheed Omar’s mauj (I am Shaheed Omar’s mother)”

She’s Fareeda Qayoom Bhat.

Fareeda is in her mid-forties. Her appearance looks unattended, and an unusual discomfort follows her steps. Instantly she passes a heart-out smile; an affirmative to the presence of a stranger. She moves to the guest room, sits carefully, and catches her tone for the interview. She firms her posture, so as to wade through a set of emotions, once again.

It was on August 25, 2010, at the peak of summer agitation when Omar was taken into custody by CRPF. Police had tracked down Omar claiming his involvement in the stone pelting.

“It was Friday and Omar had gone out to pray,” recalls Fareeda.

But before taking Omar to the police station he was beaten on the spot. According to eyewitnesses, Omar was thumped, dragged and pushed to the shop shutters, stamped upon by a few policemen and then thrown into Gypsy.

Fareeda was instantly informed about Omar’s arrest. In a shock, uncontrolled and unmindful of her clothing or appearance, she had run to the police station.

At the police station, she saw Omar from a distance. He was lying on the floor in a pathetic condition.

“When Omar saw me, he shouted out: Ammi take me to the doctor, please,” recalls Fareeda, her smile now disappearing into gloom. “He tried to get up, but he was subjected to such a severe torture that he couldn’t.”

Fareeda knew her son was not fine. She vividly remembers how she and her husband pleaded with the concerned police officer to release their son. But despite all the requests, the officer refused to release Omar.

“Are you some authority that you are directing me to do things? I will see,” the officer had commented violently.

Omar spent most of his time experimenting with electronics. He wanted to be an engineer.

“They not only took my son’s right to dream, but his right to life as well,” says Fareeda, demonstrating her resent for the system that she believes to be clothed in corruption and inequity.

Fareeda recalls that Omar was fasting on the day when he was taken into custody. It was the month of Ramadan.

Fareeda recalls that Omar was fasting on the day when he was taken into custody. It was the month of Ramadan.

After all her efforts to get Omar out were turned down, Fareeda had begged the officer to at least let her son have a glass of water, so that he could break his fast.

Like a constant picture, carefully preserved, Fareeda speaks with certainty. She tries not to let her tailored strength break, but something breaks her finally.

“When I told him, Sahab please give him a glass of water, he told me, let him urinate, he will drink the same and break his fast,” alleges Fareeda, looking away for a moment.

After a pause, she lifts the hem of her duppatta, touches it to her moist eyelids, and says, “Tem weeze gow mye setha mushkil (I felt deeply pained at that time)”.

That evening, almost every member of the family visited police station to plead with the officer to release Omar. But nothing worked. However later, Omar was allowed to talk to his mother over phone.

“When I talked to Omar, he once again pleaded: Ammi take me to the doctor.”

Next day, Omar was sanctioned a bail.

“We went to DC office; first they took Rs 500 and then they listened to us. The bail was sanctioned at 2pm, but they released him at 7,” says Abdul Qayoom, Omar’s father.

Fareeda adds, “They released him, but I received my son half dead.”

After the bail, Omar was restless throughout the night, telling his mother not to touch him even slightly. He was awake till dawn, and so was Fareeda.

In the morning, Fareeda gave him a glass of juice that he immediately puked back with blood. He was instantly rushed to the hospital, where he was put on a ventilator.

Fareeda spreads out the medical reports. The report reads “diffuse intrapulmonary heamorrage – cause of death.”

Omar was unconscious for three days, and on his fourth day on ventilator, he breathed his last.

Six years have already passed since Omar’s passed away but Fareeda’s struggle is not over yet. She regularly visits court, meets different people, lawyers and all the authorities concerned, to get justice for her son.

“Every month we go to the court, but there is no justice. All they do is try to convince us to take the case back. kuch nahi milega. Ex gratia lelo. (You will get nothing. Take money instead). This is all they say,” says Fareeda. “They all are collectively responsible for my son’s murder,” she adds.

The present status of the proceedings stands same as 5 years back.

The FIR reads: “In Order To Prevent Any Breach Of Peace And To Maintain Public Tranquillity And To Safeguard The Interest Of People, He Was Apprehended And Booked Under Preventive Measures Under Section 107/151 CRPC. He Was Kept In Police Lockup After Proper Search On Same Day Viz 20.08.2010.”

Fareeda is resentful. She’s considerate of the event, and is once again reminded of the most urgent questions of her life, “why was my son killed?”

For her, Azadi is nothing but justice. She concludes, “Aazadi aayegi jab insaaf milega (Freedom will come, when people will get justice).”