More than a century back, escaping tribal wars and British onslaught, Pashtun’s from Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkwa sought refuge in Kashmir. Safwat Zargar spends a day with them to pen their struggle for survival and identity in conflict torn Kashmir

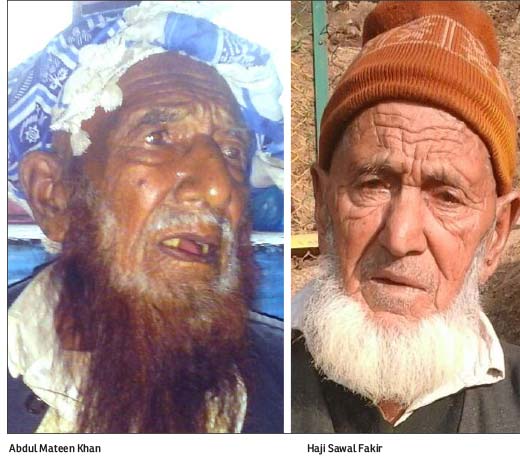

The earliest memory, Abdul Mateen Khan of Gutlibagh Ganderbal, archives of his roots in Kashmir is the late 19th century British Settlement Commissioner, Walter Roper Lawrence’s settlement orders. One of the few oldest men surviving in a community of estimated 10000 ethnic Pashtuns, Khan unravels the scope of the order under which people were asked to cultivate lands in unpopulated areas.

More than a century and a half before, his great-grandfather Shareefullah, escaping tribal wars and British onslaught in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (formerly known as North West Frontier Province) Pakistan, was living a nomadic life in Lolab valley of Kupwara. Among the many applications, Lawrence, appointed in 1889 to carry settlement operations in Kashmir, received after the announcement of order, was of Shareefullah.

“We got several thousand kanals of land. Lawrence Sahab told my grandfather to take as much land as he would be able to tend,” says Khan. Over the generations, as the community grew in number with newer groups of Pathans flocking Kashmir to the idea of settlement, the land share got divided. “At first, there were only five-to-six men including few Kashmiri Muslims and Kashmiri Pandits who inhabited the place. Pathans from Afghanistan and Frontiers thronged Kashmir for trade and labour in the past as well, most of the inflow of which, was facilitated by the Afghans ruling Kashmir (1752-1819).”

Well built, Khan’s eyesight is weak but he still walks down every day from his house, perched on a small hill, to see the cricket playing boys in the plane lap of a small mountain. In Gutlibagh, not many remember things like Khan. Khan says he is around 103-105 years old. There is no factual proof to support his claim but the recollections of past events still make him stand out from others.

One such recollection is of Dogra Maharaja Hari Singh’s injury after he fell from his horse while playing Polo. Anti-Maharaja movement that started in 1931 is etched in his memory. Khan shares a different legacy with the protagonist of that movement – a teacher-turned-freedom fighter, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah. His father, Syed Fakir and Abdullah studied in the same school in Nowshera Srinagar.

Of the India-Pakistan creation, he remembers Pandit Nehru, Gandhi and Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan who was also known as Frontier Gandhi. The unfolding fear and chaos as a result of Pathan raid in 1947 is hazy in his recollections except for the “brutal” death of 19-year-old NC activist Mohammad Maqbool Sherwani of Baramulla at the hands of Pathans.

Khan, who is the head of four generations of sons and daughters, grandchildren and their children numbering around 150 in total, also took part in one of the processions in the aftermath of 1931 uprising against Maharaja. “I went up to Ganderbal but then the Police came and lathi-charged the protestors,” he says.

A farmer throughout his life, Khan boasts of his father Syed Fakir’s formal schooling in those days. While the young boys and girls of this mountainous community are regular school and college-goers today, Mateen Khan crows about the English visitors finding only one in Gutlibagh who could talk to them, his father. He isn’t wrong.

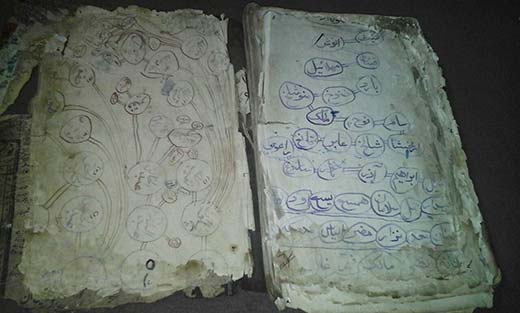

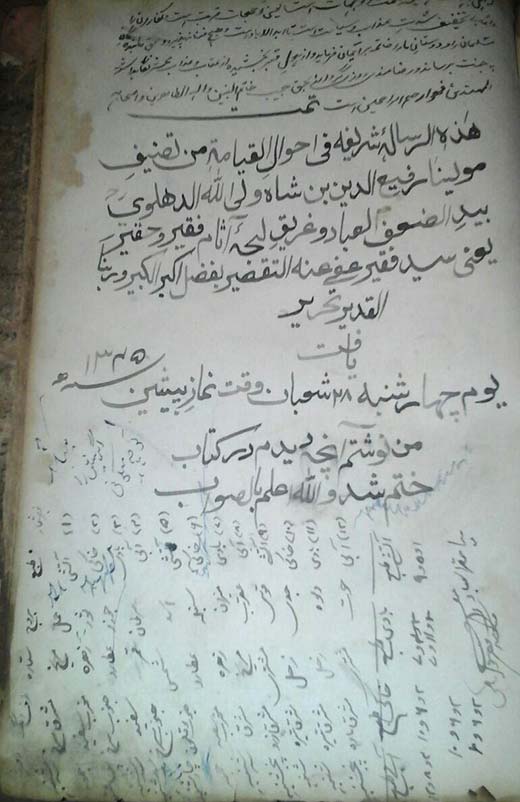

Khan still possesses the long diary of his late father in which the last written words have been neatly curved on the afternoon prayer time (Zuhr) of 28 Shaaban, 1345 Hijri, (Thursday 3 March 1927). A moth-eaten, torn, and with its oily cover falling to shreds, lines of neatly written black text with Persian calligraphy pen produces the effect of reading an archaeological manuscript, incomprehensible, but still a delight to the eyes. For entire Gultibagh the book is like a holy relic. “It is a mixture of everything; from Shajre Nasab (Family Tree) to health tips and from Islamic rulings on property sharing to the memoirs of prison, written in Persian, Arabic and Pashtu,” he says.

According to Khan, a major part of the book was written during his father’s days in prison. Khan doesn’t remember the exact charge for his father’s imprisonment except “Ek So Dus” (110). “It was actually part of the tension between Pashtuns and Kashmiri Muslims in early days,” he says, adding, “those times have gone now.”

The only alive child out of six – three sons and three daughters – of Fakir, Khan, like most of the Pashtun’s in the area, has tried to be as “far away as from whatever was happening around. We never sided with any party. Our main aim has been to survive,” he says. Like everywhere in Kashmir, the heat of armed resistance against the Indian rule also reached here. A Rashtriya Rifles (RR) camp of Indian Army in a concrete building is the evidence.

Crackdowns, raids, encounters and patrolling by Indian troops didn’t make any distinction towards the Pashtuns living in Kashmir. “We all lived those times, together,” Khan states refusing to go in details.

Khan has never gone to school, instead, he has learnt Arabic and Persian from his father. He got married at the age of 20-22 with a Pashtu girl whose ancestors still live in Abbottabad Pakistan. In fact, he once went to meet his in-laws on an Indian passport in 1978, a tradition still alive in the area. “There are very few from Pakistan side that have come here to meet their relatives,” Khan informs.

Though the community has lived here for more than a century, it has managed to preserve the distinct identity and language of their tribe. Tribal loyalties and linkages, like Afghanistan and Pakistan, find resemblance here. Jirgas to settle disputes before knocking the doors of Police and Courts are a common sight. The community has of late become flexible in education and employment of girls, even when the behaviour and attitudes of womenfolk are mostly governed by the males.

Asserting the distinction of his tribe, Khan, says he belongs to the Yusufzai tribe. Pointing towards the village downhill, Khan says the village is inhabited by a Pashtun tribe from Swat called Khan Khel.

“Our family links connect with Sayids. That is why we never marry outside our tribe,” he says while acknowledging some cases in the Gutlibagh where Pashtun’s have married Kashmiris.

While his life has usually remained confined to apples and walnut orchards, the younger generation has got accommodated in several government departments, mostly Jammu and Kashmir Police. His son, Abdul Rashid, who works in police, says “the community has preserved their language and identity even after living so far from their origins. We speak much better Pashtu then those in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Their Pashtu is full of borrowed words. It’s not pure.”

Marriages, however, have slowly synthesized with the traditional Kashmiri Muslim customs. “We also have Waazwan during our marriages but we sing Pashtu songs,” Rashid says, “but our Kashmiri guests don’t understand them. Dancing and sword fights also make our functions unique.”

Sharing the legacy of being among the eldest Pashtuns alive, Haji Sawal Fakir claims to be 140 years old. A patient of dementia, Fakir is too frail to stand up or move out on his own but being an old witness of the history, he is full of events, though muddled and haphazard in his memory.

The only clear memory Haji Sawal Fakir is proud to share is of his Hajj pilgrimage in 1979 by ship. “It took us nine days and eight nights to reach Jeddah from Bombay port,” Fakir remarks, his voice pausing and then picking up again after retaining strength. He is contend with the sacred pilgrimage he took some 35 years ago, as the number of pilgrims visiting Saudi Arabia was very less compared to today.

“Those days, 40 Saudi Rials were given in exchange of one hundred Indian rupees,” Fakir adds, another indication of his love for pilgrimage.

Born and brought up in Gutlibagh, Fakir went to a local school in Nunner Ganderbal, where he was taught by two teachers – a Kashmiri Pandit and a Maulvi. Reflecting some stray thoughts about his great-grandfather and father who migrated from Afghanistan in the 19th century, Fakir’s origins became a hindrance for his Hajj visit after the Pathan raid in 1947.

“During Pathan raids, our spiritual guide told us to save our lives and hide in the jungle. After spending a night with my family in the jungle, we returned to our homes,” he says.

Filing an application for Hajj before a high-level official at Shergari Srinagar, whom Fakir calls as “Governor”, the incident defeats his loss of memory ailment.

“The Governor replied: Aap logon ko hum Passport nahi dega, aap Kabaili hai (We can’t give passports to you. You are Kabails),” Fakir says. “It was only when I came up with my school certificate I was given a passport.”

He has misplaced that certificate now, Fakir’s grandson, Afzal says. “Till last year, he used to write each and every happening of the day in his diary but as his health deteriorated, he dropped that habit.”

Where are those diaries? “He doesn’t want them to be read by others,” Afzal reasons.

A contractor by profession, Fakir has worked on the water canal for famous Kangan Power Project. In his peak days, he used to sell thousands of walnuts to the exporters. But being in business didn’t keep him away from books, mostly Arabic and Persian. Literature and Islamic books have been friends of him since birth, Afzal says. “He can still read anything without spectacles.”

Another remembrance Fakir hosts, revolves around a visit of Prime Minister Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad to Gutlibgah. “He took bread and milk at the house of my Spiritual guide, Haji Mir Alam,” he says.

Fakir belongs to one of the tribes of Malakand district in NWFP. Survived by his two sons and five married daughters, Fakir is the head of a family of around 90 members which include his grandsons and their children.

“I won’t tell you a lie. I am sorry that I don’t remember much now,” he says after his repeated failed attempts to recall the past.

“Lies are scissors for faith,” he concludes.

Great article. I am a Pashtun from J&K and my Grand father had migrated to Poonch and his brother migrated to Lahore. I have been carrying out research on our community in J&K. We are very small community of probably around 35000 people in the entire state. Despite this we have preserved our identity to a large extent especially our language and have contacts with our relatives in KPK.