25 years of conflict has flipped many fortunes. When Basharat Shah, a Batamaloo gold medallist from AMU disappeared, his family changed forever. Guddi, his sister and perhaps the closest to him in the family, failed to reconcile with the realities around and gradually landed in a mess she herself is unaware of. Muntaha Hafizi and Sehar Qazi meet Guddi to understand what it means to lose most of the loved ones in a row

(Guddi walking aimlessly in Batamallo market.)

For 58-year-old Farhana, also known as Guddi, life is stuck in a freeze frame. Her now sullen eyes once belonged to one of the Srinagar’s top most families.

Since 22 years, wearing polka dotted pheran, and a mélange of tattered clothing, Guddi wanders about the streets of Srinagar looking for her brother Syed Basharat Shah. Basharat disappeared one fine morning during early 90s.

Since then Guddi, with a portrait sized picture of Basharat hanging dearly around her neck asks everyone; hawkers, shopkeepers, locals, army men and passersby, just one question, “Basharat ma aaw?” (Has Basharat come?)

Ask anybody about Guddi and he will direct you to lane No 9, Firdousabad, Batamaloo. Through the only open window, that’s a door for Guddi and others who visit her, the house looks barren and cold. There is no flooring, and the chill of the floor passes through as one walks barefooted.

Guddi’s life is confined to the kitchen that looks like it has been set on fire and never painted again. The windows are covered by the old ragged blankets, a replacement for the glassless windows. The rooms in the house look scattered due to September 2014 flood fury.

In the kitchen, the mattress lies rolled to the other side, half of which is burnt. Guddi has however managed to keep the place clean.

The shelves are empty except the third shelf, which has a new glass set of bone china, untouched and unused. The counter with the wash basin had everything scattered on it. Some unwashed cups, and few empty plastic jars. On the side of the wash basin an old woolen blanket lays, next to it a bucket, covered with a Dupatta.

As Guddi places herself on the old rug, near the counter of her kitchen and turns to prepare tea, she murmurs to herself, waai aasi na kunjaye? (Wish he is somewhere).

It was on October 12, 1990, when Guddi’s brother Basharat, and two of his friends, Shabir Ahmad Mir, and Ghulam Mohi Din were allegedly arrested at Sopore by an army group, later identified as 50th battalion CRPF (Central Reserve Police Force). All the three friends hailed from Batamaloo, one of the areas lying in the periphery of Srinagar. That day, they had to visit Sopore, for one of their business deals. The two tongawallas – Sultan Sofi and Sanauallah Hajam, who were hired for the travel, were also taken into custody on the same day.

Guddi looks old and tired. Hardly able to adjust with her loose, torn pheran and a worn out cap, she talks haphazardly about the events.

“Keh karukh ne, athih aaw ne kinh. (They did nothing. They couldn’t find him),” says Guddi, laughing, crying at the same time.

While the cart drivers and Basharat’s two friends, Shabir and Mohi din were released after two months of their arrest (15th December 1990) Basharat never returned. Quarter century has already passed since Basharat disappeared, yet he is to show up!

Guddi sits with a good memory. She recalls her time with Basharat. The vision of her eyes gives the feeling of longing, sorrow, and unending pain. Her face reflects that something is lost forever.

“Temis ous na professor banun, waai khodaye.” (He wanted to become a professor),” says Guddi.

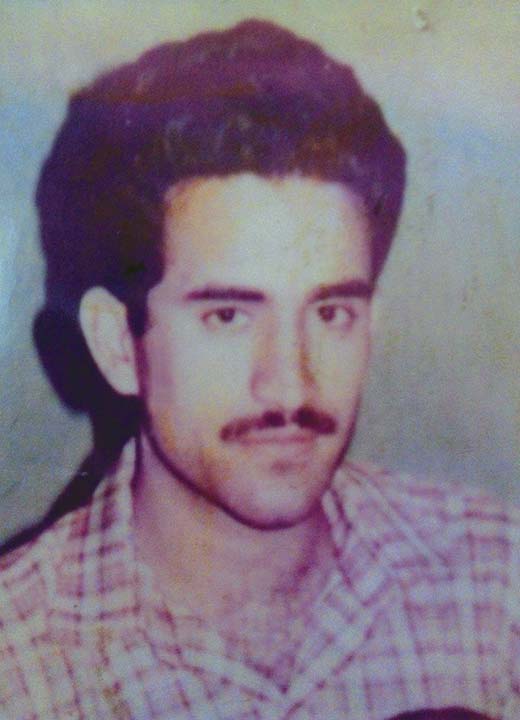

(Basharat Shah)

Basharat was born in 1967. He had his primary studies from National Public School, Srinagar; later in 1984, he joined SP College as a student of medical science. After completing his graduation in 1987, at the age of 22, he went to Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) for further studies with a dream of becoming a professor.

And, by 1989, he had completed his masters, earned a gold medal and returned to serve his homeland.

Being a young anxious person, like many other Kashmiris, when Basharat returned he understood that the political issue of Kashmir was not resolved the way it was promised in 1947. And it was a time when people were taking positions, and joining various organizations to make Kashmir an independent nation.

“Like any other Kashmiri, it was not possible for Basharat to live in isolation especially when resistance wave was going on. Basharat was developing in that period of killings and confrontations,” says one of his close friends from AMU.

Basharat belonged to a well known family in Batamaloo. His family included his father, Mohammad Amin Shah, a government employee, his mother, Haleema, a government teacher, his younger brother Nazir Ahmad, currently a business man and Guddi, who was his cousin sister.

Guddi was three years old when she was adopted by Basharat’s mother Haleema. Later in 1987, Guddi was settled and married into a well known family by Haleema.

Being almost 10 years older to him, Guddi loved Basharat like a son, and with his disappearance, an immense pain had took her over.

“Be chas pemis asmaan. Meri museebat J&K ne dekhi hai. (I am crestfallen. My pain is known to everyone in Jammu and Kashmir),” says Guddi.

Guddi looks around at the house and says, “Ye ghar haleema ji ne banaya hai (This house was built by Haleema).”

It was after few years of Guddi’s marriage that her life took a flip. Her husband had started torturing her. Knowing that things were not well, Haleema constructed a separate house for Guddi, now a souvenir for her.

In between the dispute, Guddi gave birth to two children, Tabinda and Hamad.

While Basharat’s disappearance had come as a shock for the family, and everyone had tried to cope up with the loss, Guddi got into an emotional crisis.

For Guddi, it’s a history still alive. In her broken Urdu, she says, “Do I have to tell you history? I have got attacks.”

Guddi shouts, Cze kadakh herat. Pagal khan te souzhes. Lekh history (You will be surprised. I have even been to asylums, write my history).

As Basharat’s family was visiting every jail to find him, Guddi searched for him in temples and shrines. But there was no clue of him anywhere.

“Ye cha Biography akh. Mandaran te aastanan te aayas pherith! (This is a biography. I went to every temple and shrine in Kashmir, to look for Basharat),” says Guddi.

After the release of tangawallas, Basharat’s family came to know that he was arrested. Some other facts were also revealed, by the other two friends, who accompanied him that day.

“When CRPF arrested us, they started beating tongawallas ruthlessly. On that, Basharat grew angry and got into a heated argument with the army men. Thereafter, they started beating Basharat, and he started bleeding profusely,” says Mohi din, one of his friends who was with him that day.

On that day, Basharat was taken to the other room by the army and interrogated.

“The army took him to the other room, and we could hear him screaming, and after some time, we heard one of the army men saying ‘Yeh sala tou thanda hogaya’ (He is dead). After that, we didn’t see him ever,” says Mohi din.

In the process of finding Basharat a well off family like his, had to sell their land to keep the search and hope going.

By January 1991, when Basharat’s family failed to locate him, they finally approached an advocate to fight his case.

Guddi remembers everything related to Basharat’s disappearance – the lawyers, the leaders, and the pending case.

“Tehreek” word is etched in Guddi’s memory

“Case toh wahi hai. Ji case toh wahi wahi, jab se tehreek hai (It’s the same case. It is pending since 1991),” she says repeatedly.

Guddi shouts all of a sudden with anger, “Likhli biography, aur kuch, aur kuch? (Did you write the biography, anything else?)”

Then flashing a sarcastic smile Guddi says, ‘even that lawyer is dead, everyone is dead’.

Pain has always followed Guddi dedicatedly. In search of Basharat she couldn’t even see the childhood of her children, who were taken care of by Haleema.

In between the conversation Guddi often stands, messes with the jars and sits back.

“Mye chane payi mye kati korukh korui khandar, lukh aes wanaan Sopore (I don’t even know where my daughter is married. Or when. People say she is married and settled in Sopore),” says Guddi.

She stops and cries and then suddenly remembers that Sopore is the same place from where Basharat went missing, “Wei basharat te nuke na teth” (That’s the place where from Basharat was taken away).

As Guddi talks, her words are followed by a long silence. She loses herself and comes back to the memory of Basharat.

“Haa case toh Basharat ka hai. Su chu diwaan toolas ti zuv, agar aasi zinde te yeetan. (Yes, the case is of Basharat. God gives life to everything. If Basharat is alive why won’t he return?),” says Guddi, hopefully.

But like most of the disappearance cases, some 8000 pending in Kashmir since 1989, Basharat’s case was also overlooked.

After advocate Malik’s intervention the High Court had directed Inspector General and Deputy inspector general CRPF, to reveal the whereabouts of the Basharat within two weeks. But there was no response. After that High Court had directed Chief Judiciary Magistrate Sopore and Superintendent of police Baramulla to hold an inquiry. It was after a month that a report was submitted, and as per the report they held 50th battalion for retaining Basharat. FIR was lodged against them under number: 184/91. It was six months before the registration of FIR, that the battalion was shifted to Assam.

(A family portrait.)

“The SHO demanded Rs 8 lakhs to go to Assam and prosecute the commander, which then, they never did,” says Basharat’s brother, Nazeer Ahmad. “The Home Ministry had denied the permission despite the fact that all the evidences were against the battalion. After this the case was also forwarded to the, Amnesty International in July 1991,” says Nazeer Ahmad.

In every next minute, the expression on Guddi’s face change. Now her expression turns gloomy, as she’s reminded of Basharat again.

“Posai yeth nyeeekh (They only took money),” Guddi laughs sarcastically and then stops and after a brief lull says, “korukh ne kinh (They didn’t do anything).”

“Khabar kus osus pateh, asi sondh hari jaaye, waai khodaye (Someone was after him, we looked for him everywhere),” says Guddi, looking at the door, cautiously.

For Basharat’s family, it was a long struggle. After waiting for his son for 12 long years Basharat’s father died in 2002. Then the search for Basharat was taken up by his mother, who died in 2013.

And after the death of Haleema, Guddi left her brother’s house and started living alone. Now she wakes every day to look for Basharat in the lanes of Batamaloo.

“Yeti batamalin mood saeri, saeri maerikh (Everybody in Batamaloo is dead. Everybody has been killed),” says Guddi in a matter of fact manner.

Batamaloo in the heart of Srinagar city is a curious place. It is said, at the peak of militancy there used to be lanes ruled by militants entirely. Even the last notorious bunker, located at Rek Chowk, has gone now.

Besides, Batamaloo is also known as “Land of Martyrs”, a place with large number of crackdowns, killings and disappearances. The place lies in the periphery of the areas such as Gawkadal and Tengpora, known for two big massacres in history of Kashmir.

Despite of such a long struggle, Guddi is sure that one day Basharat would return, as she says, “Thaper laayes, wanas kati osukh (I will slap him and ask him where he was?).”

She still wants to know if someone has seen Basharat anywhere.

Guddi ends her conversation, with a look of worry. As she stands at the window for a farewell, she asks in a hurry, “Police ma yee beyi ha, Police ma yee? (Will police come again?).

Thank you Kashmir Life and its team (especially Muntaha Hafizi and Sehar Qazi) for such fantastic and indepth reporting from the dark corners of Vale of sorrows. I highly appreciate what you people do for the generation to come. Once we lose our past, we cannot have a future. So once again KL and its team for keeping our past alive. No matter how painful it is. And May Allah bless Guddi.

This is such a brilliant story. This made me cry and reminded me that there’s so much our Kashmir has witnessed.