Started by an emergency ruler during Kashmir’s transition from Dogra Raj to the Delhi era, Radio Kashmir has been airing voices for nearly seven decades now compelling Kashmiris to lend it eager ears. But amid successful stint of corporate radios presently and the emergence of new forms of media, Saima Bhat reports why Kashmiris love, hate and always react to the broadcasts of Kashmir’s ‘grandest’ radio

Beyond paramilitary pickets and checkpoints, Radio Kashmir (RK) is busy broadcasting voices. Positioned in a sleepy ambience, the station with nearly seven decades of history is presently struggling to keep tabs and tune with changing times.

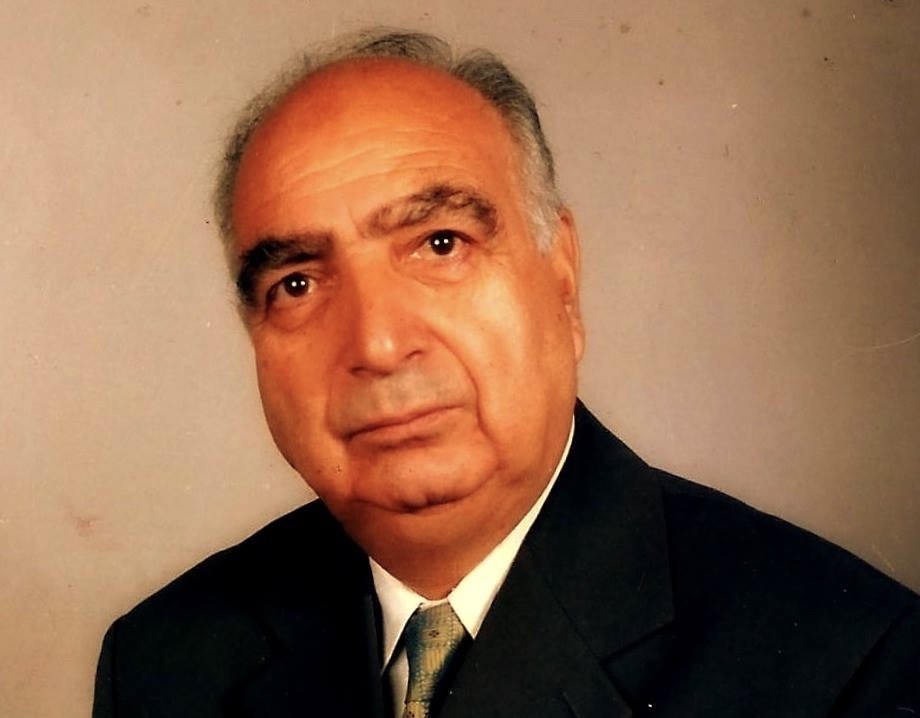

But an ace broadcaster, Syed Himayun Qaiser, is upbeat and thinks otherwise. His belief stems from his service rendered in RK during its trying times. The pits petrified the station in tumultuous 1989 – the year Qaiser joined the station. And shortly the broadcaster of Dhadkan fame witnessed the worst taking over.

“The station would receive regular notices through newspapers, asking its employees to leave the job, or face consequences,” recalls Qaiser, now heading the station. The threat was too real to downplay, he says, triggering a panic plus a chain reaction inside the station. “All of the sudden,” says the broadcaster, “the employees working here either got themselves transferred, or quit their jobs.”

The threat cost the station dearly and went on to fade its glory – as the outgoing staff left a big void behind.

The show was then managed and run by a mere 30 per cent remaining staff, staying put despite life threats. The commitment of these men and women never let RK go off-air. However, the absence of accountability and intrusion of non-professionals during that time did mar the grace of Radio.

But more than grace, then, it was the question of survival, says Qaiser. “During those difficult times, we could manage to do the unthinkable with the belief that ‘radio must not go silent’.” But letting the radio speak amid pervasive silence around took its toll on the handful of staff.

Each person had to handle at least 10 programmes a day. And to avoid frequent curbs, curfews and crackdowns, they used to stay in the office for days together. “We used to come early 6 in the dawn and leave at around 7 in the dusk when nobody was even visible on the roads,” Qaiser says.

Even after sailing against the wind, the handful of broadcasters couldn’t prevent the worst from creeping inside the station. It faced an abrupt shortage of engineers, programmers, and even administrative staff. After the assassination of the then station head, Lassa Koul, RK was entrusted to senior broadcasters and programmers, Farooq Nazki, heading Doordarshan Srinagar simultaneously.

Perhaps not many know that the paucity of staff and uncertain times triggered another rot inside the station.

“All of a sudden,” recalls Qaiser, “we became informal, much more informal than RK ever was. Earlier, I mean pre-89, we used to converse in formal and literary language. But it suddenly changed when fresh blood came into the radio.” The new environment went on to erode the elegance of the station it was earlier known for, he says.

But much before the worst took over, Kashmir saw RK being established, inaugurated by then Prime Minister Sheikh Abdullah in 1948 in Srinagar near Abdullah Bridge. Ghulam Mohi-ud-Din was appointed its first head. But as it turned out, the station could never stay away from politics and political control.

In 1953, when Sheikh Abdullah was incarcerated, observers say RK Srinagar came under the control of All India Radio to counter Radio Azad Kashmir. “Both these stations were used to counter programmes aired by each other,” says one elderly employee of the station. “When the Azad Kashmir Radio used to air ‘Zarb-e-Qaleem’, it was countered by Srinagar station’s ‘Jawabi Hamla’.” Later another “propaganda” programme, Wadi Ki Awaz, was aired to safeguard the “national interest”.

But more than an “official tool of propaganda”, RK shot to prominence for its contribution towards the traditional music of Kashmir. Celebrated singers like Ghulam Nabi Dolwal, Ustad Mohammad Abdullah Tibet Bakal, Ustad Ghulam Mohammad Qaleenbaft, Ghulam Qadir Langoo, Raj Begum, Naseem Akhtar, Nasrullah Khan and many others were noticed and admired across valley after provided platform by RK. “It helped to keep Kashmiri musical tradition alive,” Qaiser says. Besides music, he says, RK worked relentlessly to save the Kashmiri language, literature and culture.

The plays and dramas aired from RK were equally intriguing. It rose to fame when Pushkar Bhan’s Zoon Dab was broadcasted. For more than nineteen years, the programme enthralled and entertained the listeners with the portrayal of realistic content – a reflection of a typical lifestyle of a Kashmiri family.

Apart from entertainment, people would turn to RK for news. The cherished broadcasters like Abdul Rashid, Abdul Ahad Farhad and Moti Lal Khazanchi added credibility to the news script through their voices. Among the news programmes, Shehar Been became a massive hit.

However, in the face of gun revolt in Kashmir, the officials and newscasters of the sister department of Prasar Bharti news room shifted its base to Delhi, where it would air the news with this intro: “Ye radio Kashmir Srinagar hai, ab ap Naye Delhi se khabrein sunye!” (This is Radio Kashmir Srinagar; now listen to news from New Delhi).

But over the years, RK serving as a link between people and the government failed to produce erstwhile artists like Manohar Prothi, Shanta Koul, Mohammad Amin, Kedar Sharma, Som Nath Sadhu, Maryum Begum, Poshkar Bhan and others.

The overwhelming situation in the valley forced most of the scholars, scriptwriters and artists to boycott the Radio. “Because of least staff, casual culture crept in RK during that period,” says the former broadcaster. “This situation marred the professionalism. Technical snags, poor vocabulary and repetitive mistakes thus became the norm of the day.” Amid mediocrity, the heightened security measures apparently turned the station into a garrison, sealing its entry for commoners.

However, introspection took over at the fag-end of 1995. To alter the public perceptions, the station then started the first phone-in-programme on the eve of New Year 1995, where listeners were encouraged to call in. To introduce it, proper advertisements were floated through newspapers – read as RK’s “falling grace” sign.

And then continuing the trend, RK started phone-in programs like Mujhai kuch kehna hai in 1997. The programme was promoted with a tagline: radio is just a phone call away. This was followed by a series of phone-in music, grievances, discussion, science, sports and other programmes. “All these programmes were aimed to bounce back the public focus to radio,” Qaisar asserts.

By 1997, RK became a corporation, suspending all new recruitments, citing recruitment rules. Since then, the recruitment for news readers and announcers officially stands shut.

“Many posts are vacant in RK, but as per the guidelines, vacancies for announcers, and news readers are already over,” says the incumbent head of the station. “No new people get recruited. It’s a policy that all news readers will be casual. In future, all announcers will also be casual.”

Interestingly, this norm is prevalent in the station when mere 6 staffers are operational with 80 casual labourers, having “no media background”. What further disturbs is the fact that most of those engaged in RK on a need basis are already doing government jobs.

And the latest is, around 30 people have been freshly hired – but among them, only one is Kashmiri.

Amid the mounting complaints, many say, people still have a reason to glue to their radio sets to hear popular programmes like Shaherbeen and humorous broadcasts by celebrated broadcaster, Talha Jahangir.

But mainly, the station is on demand for its pre-ninety content, sufi songs and folk music. And to keep the same public mood in mind, the station has digitized around 40 per cent of its records. “The complete process will take some time as the station houses records of the last 60 years.”

However, to stay relevant at a time when a corporate-run FM station is already popular in the valley, RK started the 10-kilowatt FM transmitter during the previous dispensation headed by Omar Abdullah. The FM channel “103. 5 MHz” airs programmes for youth, interactions on social issues, covering of live events at Kashmir University, colleges and schools.

“But the kind of content RK now offers doesn’t seem to lend it a serious audience,” says Basharat Khan, an avid radio listener. “Earlier literary giants like Ali Mohammad Lone, Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din, Sajood Sailaniand others would write RK’s script, but now every other person is their scriptwriter.”

Despite its issues, however, RK continues to remain popular at the grassroots where it has the highest audiences. And from the last three years, the station has been broadcasting live and other programmes to woo its listeners. Everyday programmes get broadcasted in eight different languages, Gojri, Dogri, Sheena, Balti, Punjabi, Kashmiri, Urdu and Hindi.

“We have to face competition always,” says Qaiser. “But radio was there when TV came in and now it’s there when other radio stations are also there.” But still, he says, RK has its own loyal audience who “trust it for information, entertainment and education”.