In its attempts to create a foothold in the greener pastures of Kashmir, BJP over the years roped in valley’s political-nobodies, even holding hands of counterinsurgents. Safwat Zargar traces the emergence of India’s right-wing on Valley’s political landscape to create its stakes within a short span of time

At a distance of around thirteen kilometres from pro-freedom bastion Sopore, a silent village, Rohama, nestled in between apple orchards, is the “Maatribhoomi ” of 54-year old Mohammad Maqbool War. The uniform austerity demonstrated by houses in the village makes it hard to point out War’s residence till one catches the eye of two Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) flags, nailed to the tin-sheet fence encircling War’s compound, struggling to unfurl in the coldness of the weather.

Mohammad Maqbool War’s introduction is BJP. Throughout the area, his “unusual” saffronized legacy precedes him that he took over after contesting 1996 elections on BJP ticket. For War, the reason for joining politics was “compulsive” than “ambitious.”

On April 26, 1990, War’s father, Ali Mohammad War, a retired sub-inspector of J&K police, was gunned down by militants at his residence. “After my father’s casualty, local militants continuously harassed me would ask for money time and again,” War says, while sitting near an open, glassless, window of his old one-storey house. He talks in a heavy but clear voice, his narration marked by typical Hindi words.

After marrying off his only sister in August 1991, War started spending most of his time outside Kashmir in connection with his fruit business. In 1992, War opened up a fruit shop Maqbool Fruit Centre (MFC) in Azadpur Fruit Mandi, Delhi. “I thought of disposing off everything here and settle in Delhi. But my mother and wife didn’t agree.”

Tracing its roots from Bharatiya Jana Sangh led by Syama Prasad Mookerji, BJP was formed on April 6, 1980. The party, considered to be having strong ideological and organisational proximity with Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), was established as a result of dismemberment of Janata Party (1977-80), formed as an amalgamation of Jana Sangh and other fluid parties with diverse ideologies to oust Indira Gandhi-led Congress.

With Jammu and Kashmir’s complete integration with India as one of the prime agendas of Jana Sangh, the death of Shyama Prasad Mookerjee in 1953 in the custody of state government, inked pages of post-partition Kashmir history with another colour. Accompanied by young Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Mookerjee had entered the state of J&K by violating exclusive entry laws enshrined in its constitution (now eroded). While the young Vajpayee returned back, Mookerjee was arrested. The 1953 event would continue to symbolize the Hindu right-wing’s “integration” plank, even more than sixty years after his death.

As a Hindu majority party, mostly alien to Muslim majority Kashmir, it fielded three candidates (two Kashmiri Pandits and one Muslim) in 1983 assembly elections in the region.

The party’s first-ever Muslim candidate was Sheikh Ghulam Rasool from Nagin seat, who could bag only 307 votes. The number of candidates fell by one in 1987 polls. Only two candidates, both Kashmiri Pandits – Om Prakash and Teka Lal Taploo – fought from Amira Kadal and Habba Kadal constituencies. Despite nearly 75 per cent voting and allegations of mass rigging, the duo managed only 1947 votes.

In September 1989, Teka Lal Taploo, a lawyer and BJP’s president for Kashmir unit, was killed by militants. With governor’s rule imposed on¬ January 20, 1990, in the state as a result of bloody war unfolding on the streets of Kashmir, there was a complete lull in the pro-India electoral arena in the region.

War’s entry into BJP is routed through apples. In Delhi, War, while sharing his worries and violence back home with his business friends, came close to a relative of Shanta Kumar, the then Chief Minister of Himachal Pradesh and who later served as Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution in Vajpayee led NDA. After some time, War was brushing shoulders with Kumar himself. “I discussed my problems with him. Shanta Kumar took me to Kidar Nath Sahni (former RSS pracharak and Jana Sangh leader) who was one of the senior leaders of BJP in Delhi that time,” he says.

“In February 1996, Sahni gave me a letter for Chaman Lal Gupta who was then state president of BJP. Gupta told me to go home and start the party’s work there. He promised to provide all help. Till I left home for Delhi, Gupta had been replaced by Vaid Vaishno Dutt as state president. I found Dutt’s behaviour and attitude more genial and loving. I shared my concern of security with him,” War says.

“Hum aam vyekti ko security nahin de sakhte hai. Security ke liye aap ko election ladna padega. (We can’t give security to a common man. For that, you have to contest elections),” Dutt replied.

For War, contesting elections was a tough ask. Even though remaining in contact with BJP leadership, War hadn’t subscribed to the party membership yet. He was worried about the loss to his business. “Sahni told me to get ready for May 1996 parliament elections but I refused because most of the fertilizer and chemical treatment to plants is carried out during this period. At the same time, I had already started squeezing my business.”

It was in June 1996, War formally joined BJP under the leadership of Dutt by paying an active membership fee of Rs 200. For assembly polls scheduled in July, War got the ticket for Rafiabad. This got him four Personal Security Officers (PSOs), a car and driver from Jammu security line.

Out of BJP’s total 13 candidates in the contest – three in Srinagar, two in Budgam, seven in south Kashmir and one from North Kashmir – six were Muslims. Post-results, War, having secured 1014 votes, ranked first among Muslim candidates. While BJP secured eight seats in total, it failed to score in Kashmir.

During elections, BJP’s candidates in Kashmir hardly knew about each other. In fact, it was during one of the party meetings in Jammu, War came to know that one Showkat Hussain Wani was fighting from Anantnag assembly seat. The post-election assessment meeting included some senior leaders of BJP and RSS like Bhagwat Swaroop, Indresh Kumar and K N Sahni. After the meeting, BJP’s state president Vaid Vaishno Dutt told War to contest Legislative Council elections in 1997 from Kashmir.

War arrived in Jammu in February 1997. Two days before the Council polls, to be held on March 17, Lal Krishna Advani, the then All India President of BJP, asked War: “What do you think? Will you be able to do it?”

“Advani gave me a Bank of Baroda cheque book and told me to spend as much as I wanted,” War says, “he wanted a seat at any cost.”

War’s response was full of optimism and confidence. “Advani jee, hamaare electionun mai painsa nai lagta. Hum jo vote lengay dil jeet ke lenge (Mr Advani, we don’t need money in our elections. Whatever votes we will secure will be by winning hearts)”

In order to become an MLC, War needed 26 votes. BJP’s D K Kotwal, who was fighting from Jammu, had seven candidates against him; War had one –Mohammad Aslam Uri, son-in-law of senior National Conference parliament member Mohammad Shafi Uri. War’s chief counting agent was L K Advani and his polling agent was Vivek Dadhakar, now organisational secretary BJP for Dadar Nagar Haveli / Daman & Diu.

On the polling day, War took 20 votes, two were rejected and he lost. In Jammu, Kotwal had only secured ten votes but owing to divide in vote share among seven other candidates, he won. Back to the party headquarters after celebrations, at around 2:30 AM during the night, Advani handed over an appointment letter to War.

He was officially designated as state-vice president Muslim Minority and Kashmir in-charge.

The announcement of official position in the party, War says, increased his interest in politics. From his own money, he rented an office at Parraypora Srinagar and opened another wing in Baramulla. War also managed to get a Pandit building from the government and get CRPF deployed there. To turn the vacant building in a liveable place, War bought furniture, matting and other necessary items from his home. “I was all alone. Showkat Hussain Wani worked in Anantnag and used to visit the office once in a while,” War says.

In the same year, War was appointed as Kashmir president BJP and soon he was provided hotel accommodation and other facilities in Srinagar which facilitated his stay in Srinagar city adhering to party wish.

Almost eighteen years back, a simple farmer family in North Kashmir’s border village of Uranbua in Uri got entangled in a fight for justice. The three children, who had lost their father at an early age, were in a land dispute with their uncle, who according to them, had sold off their share of family land. Among the three children was Haleema Akhtar, the only sister of two brothers. Born in 1976, Haleema, in her late teens, became the front-runner in the fight for justice. Justice eluded her where ever she went. Unrelenting, Haleema says, “My uncle’s son who was a soldier began to harass our family. Soldiers also began to stalk me.”

Finding Kashmir a desert of injustice, she went to New Delhi in 1996. A tenth-class pass out, Haleema left her job at the Social Welfare department to meet Lal Krishna Advani. After narrating her “ordeal” to BJP president, Advani rang up GOC of Army at Baramulla, Raj Mehta, in front of her, and told him: “Why are your soldiers harassing a woman fighting for justice? Soldiers shouldn’t get involved in family matters.” Back home, the harassment stopped but justice was still distant.

In 1998, Haleema joined RSS or what she calls Sangh Parivar. She participated and coordinated in different “peace and development” programs funded and coordinated by Sangh’s different wings for inhabitants of the mountainous region and underprivileged people.

“Our priority was widows and injured,” says Haleema, who coordinated around three programs every year in her area. Her Sangh affiliation ran parallel to her participation in programs of BJP’s ‘Peace Council’ in the valley.

In 2000, she formally joined BJP. Since then, every year, she participates in a three-day Islamic Aalima course – conducted by the party for Muslim members. A mother of two, Haleema has travelled extensively throughout India to ensure her participation in a number of RSS and BJP programs.

Before she fought her first election in 2008 from Uri in which she ranked eighth with 655 votes, she took speech lessons from senior female BJP leader Sushma Swaraj in Delhi. With her party’s “political backing” Haleema finally won the land case in 2010. From Atal Bihari Vajpayee to Arun Jaitely, Haleema is known to everyone, she says. She has met Modi four times.

Before she fought her first election in 2008 from Uri in which she ranked eighth with 655 votes, she took speech lessons from senior female BJP leader Sushma Swaraj in Delhi. With her party’s “political backing” Haleema finally won the land case in 2010. From Atal Bihari Vajpayee to Arun Jaitely, Haleema is known to everyone, she says. She has met Modi four times.

On the eve of Indian Republic Day in 2011, Haleema was entrusted by her party to organise a rally in Lal Chowk on 26 January. To save her skin, Haleema had devised her own kidnapping because “it is not good for Kashmir. The policy of flag hoisting would cause damage to Kashmir. So I tried to avoid organising the rally and did this.” During “three days of her feigned abduction”, Haleema had stayed at her friend’s house in Bemina Srinagar.

Pertinently, BJP spokesperson in Delhi, Prakash Javadekar had blamed J&K police for her “abduction.” “Our Uri Assembly constituency candidate in the last elections, Haleema Akhtar, was picked up by the police and taken away blindfolded. She was tortured for three days and then dumped,” he had said.

During the 2014 parliamentary election, Haleema was Kashmir in-charge for three constituencies. In recently concluded polls, she was a member of the election management team along with Dr Jitendra Singh and Dr Ashok Koul.

Haleema’s first official post in the party was district president for Baramulla. Before remaining state executive member for three years, she was Kashmir province women president for three years. Presently, she is state secretary of BJP and National Council Member.

As BJP had scored its first-ever parliament victory from J&K by winning Udhampur seat in 1996 and with NDA looking stronger, the 1998 parliamentary elections witnessed BJP sparking interest in senior politicians from Kashmir. The party managed to rope in senior NC leader and twice MP Abdul Rashid Kabuli to contest from Srinagar. Kabuli stood at third in the overall vote tally. However, unlike War and Haleema, Kabuli’s joining of BJP had roots in his “close friendship” with Vajpayee “during early days in parliament.”

“It was not for power. My only aim to join BJP was to solve the Kashmir issue,” Kabuli says. “I was able to convince Vajpayee to take initiatives in solving the issue which continues to be a threat to peace in the sub-continent.”

Kabuli, who claims to have played “a crucial role” in Vajpayee’s handshake with Pakistan, quit BJP in 2002 after Gujarat riots. “I sent my resignation letter to Vajpayee. He didn’t reply.”

On the other hand, in 1998 parliamentary elections, War was denied ticket by Sahni to contest from Baramulla. “I told him if you don’t give a ticket to me then I won’t campaign for a candidate who will be fighting from there,” War says. Din Mohammad Cheeta got the ticket and War shifted to Jammu where he led the campaign for Vaid Vaishno Dutt. The party won two seats – Jammu and Udhampur – out of six in the state.

In 1999 parliament elections Kabuli, who was then holding the post of state vice-president, was replaced by Fayaz Ahmad Bhat as the party candidate for Srinagar parliamentary seat.

Historian and columnist PG Rasool says Hindu right-wing’s entry into Kashmir politics dates back to 1931 Muslim uprising against Dogra Maharaja. The uprising had been triggered by the “inhuman” treatment of Kashmiri Muslims by Maharaja in the form of begaar, unequal rights and other deprivations. “In 1929, the Maharaja’s Bengali Prime Minister of Kashmir Sir Albion Rajkumar Banerjee resigned. And one of the reasons he gave was that ‘Kashmiri Muslims were treated like dumb driven cattle.’”

The statement created a stir in the sub-continent about the conditions of Kashmiri Muslims and 1931 marked the start of active resistance. “The country of Jammu and Kashmir, officially a Hindu state, since, existed in the consciousness of mainland India as a Hindu kingdom. The 1931 uprising was seen as an attempt by Kashmiri Muslims helped by Muslims from other regions to overthrow a Hindu ruler.”

According to PG Rasool, who has written widely on the origin of Kashmir dispute, much of the reaction to 1931 was witnessed in Punjab where Arya Samaj and Hindu Mahasabha movements were strong. “Kashmir became a cause for them,” he says.

Many historical accounts suggest after 1931, Maharaja Hari Singh encouraged Hindu nationalist RSS to open shakas in Jammu region. In 1947, the “role of RSS volunteers in the ethnic cleansing of Muslims” has been documented over the decades by academics and historians. The start of Praja Parishad movement in the 1950s by Jana Sangh’s Mookerjee was another attempt at “assimilating” Muslim majority Jammu and Kashmir in the Hindu nationalist dominion.

The slogan “Ek vidhan, ek pradhan, ek nishan” one country, one constitution, one flag, reflects the basic notion with which Hindu right-wing looks at Kashmir. “The decades-long attempts to make inroads in Kashmir have repeatedly failed in the past,” says a senior Kashmiri journalist, wishing to remain unnamed. “This is precisely why post-90s BJP turned into a safe haven for counter-insurgents. It was like a happy marriage; on one side was a party desperate to have some people who would at least whisper its name in Kashmir and on another side was a group of Kashmiris who were unacceptable to the society due to their conduct during their affiliations with the counter-insurgency grid.”

On January 9, 1999, a district president of Hindu far-right political party Shiv Sena, Abdul Rashid Wani along with his Personal Security Officer (PSO) was killed in an ambush near Hatlangoo in north Kashmir’s Sonawari. Police accused militants of the attack, but the recovery of carbine bullets from Wani’s body during autopsy belied police claims, a carbine is a police weapon. Subsequent investigations had indicted Wani’s deputy Altaf Ahmad Khan in former’s killing.

According to police, Wani and Khan were surrendered militants who after failing to get rehabilitated elsewhere sought refuge in Shiv Sena. The duo also failed in politics and as a result, took the route of extortion and loot. The animosity between Wani and Khan, Police said, arose after Khan was denied his share of six-seven lakh rupees of looted money, which the duo had collected together.

In a late-night police raid on January 5, 2015, around Lal Chowk Srinagar, a suspected militant namely Tanveer Ahmad Baba, alleged to have been actively working for BJP in recently held assembly elections, was arrested by police with some explosives. While the police haven’t confirmed anything yet, Baba, as per the news reports, would take reporters and other people to the BJP’s Friends colony office to introduce them to the state leaders. At the BJP’s office, Baba reportedly asked people to support and vote for the BJP in polls.

The Debutants

One of the early leaders of BJP post-1996, Showkat Hussain Wani from Akingam Islamabad, known for his “links” with counter-insurgents, contested four elections – 1996 and 2002 assembly polls and 1998 and 1999 Lok Sabha elections – on BJP’s ticket. He left BJP after 2002 polls, party sources say, and contested 2008 elections from Anantnag as an independent. By the fall of 2014, Wani was back in BJP again.

Another senior leader of BJP and a former “counter-insurgent” Mushtaq Ahmad Malik alias Mushtaq Noorabadi joined BJP in the late 90s. He fought his first election from Noorabad on BJP’s ticket in 2002. Noorabadi, who is currently President of BJP’s Muslim Morcha, contested 2014 parliamentary as well as assembly polls from Noorabad. In the latter, he got 648 votes.

Mohammad Ashraf Hajam alias Azad, a barber from Soibugh Budgam met BJP leaders on January 26, 1992, led by party president Murli Manohar Joshi, who was in the valley marking the end of Ekta yatra (Unity March). Azad, allegedly an “ex-counter-insurgent”, who mostly remained in Jammu fearing threat to his life after his three houses were burnt down by militants, claims to have joined BJP in 1993. He traces his BJP affiliation with his old RSS friend and now Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. However, Azad fought his first election in 1996 from Budgam on a ticket of Jammu and Kashmir Awami League (JKAL) which was the political arm of Kukka Parray led counter-insurgency group Ikhwan-ul-Muslimoon.

In 2002, Azad fought on BJP’s ticket and stood at fourth rank. With 1051 votes in 2008 polls, Azad’s rank slipped to seventh. In 2014 polls, Azad says party high command advised him at last minute “not to contest elections.”

BJP’s 2014 assembly candidate for Devsar and party’s highest vote-getter in Kashmir, Fayaz Ahmad Bhat from Kund Qazigund says “at early stage renegades were in the party and he has always fought to clean up the party of renegades. I cannot tolerate a person whose hands are red with the blood of innocents.” His “anti-renegade” campaign Fayaz says, earned him many “enemies” and was “attacked” several times. Interestingly, police sources reveal that Bhat, who enjoys a “good rapport” with army top brass due to his “social work”, was himself “seen with counter-insurgents” during his early days.

Founder of “Jammu and Kashmir Peace Foundation (JKPF) – a non-government, non-political global movement for peace, prosperity, brotherhood and communal harmony”, Bhat has been working closely with politicians from all parties and Indian army on different “peace initiatives in Kashmir.” One politician who has helped him throughout is Democratic Party Nationalist patron and former MLA Ghulam Hassan Mir. The website of JKPF is full of Bhat’s photographs along with politicians, state governor and army officers, in different programs held by the foundation.

According to Bhat, JKPF, whose chief patron is governor N N Vohra, was a brainchild of former Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. A recipient of Sadbhavana Ke Sipahi Award in 2004 for the “service of widows and orphans,” Bhat, who contested parliament elections twice in 1999 and 2014, says “his politics is for providing relief and rehabilitation to conflict-torn Kashmiris.”

One of the senior members of BJP in Kashmir, Sofi Yousuf, who contested 2014 assembly polls from Pahalgam, joined the party in the late 90s. A police constable by profession, Yousuf is remembered in his native village Srigufwara Islamabad, as a counter-insurgent who was seen mostly in one of the “notorious” headquarters of the group in the area. Yousuf headed BJP’s Kashmir unit from 2003-2008.

He contested his first ever election on BJP ticket from Bijbehara in 2002. He was also BJP’s Lok Sabha candidate for Anantnag parliamentary seat in 2004. Yousuf ended up losing in both 2008 and 2014 assembly polls from Pahalgam.

BJP’s media in-charge Kashmir, Altaf Thakur owes his BJP joining to Mohammad Maqbool War of Rafiabad. A resident of Dadsar Tral, Thakur, a former class fourth employee in Kashmir University, joined BJP in 2007 as an office secretary. “He was terminated from his job over a fraud of severe nature and that is when he expressed his wish to join BJP,” War says. “I took his two photographs and got a party identity card made for him.”

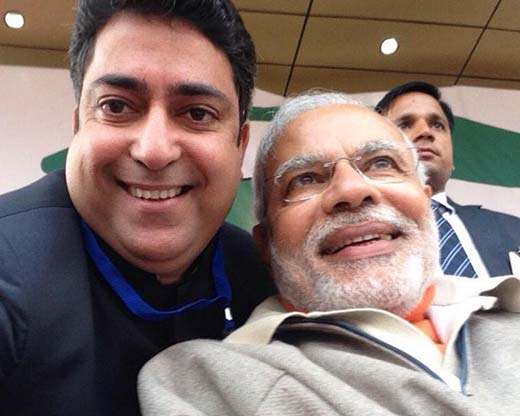

Months before Modi would be sworn-in as 15th Prime Minister of India, a Kashmiri journalist along with former Inspector General of Police who formed Special Task Force (STF) to counter militancy in Kashmir, were welcomed by Modi at a rally in Hiranagar Jammu.

“I do not know whether the friends in media will pay attention towards this news. Today the former IG of J&K, Farooq Khan has joined BJP. Khalid Jahangir, (a Kashmiri Journalist) an expert on writings on conflict areas, has also joined BJP. He has carved a niche in the field of journalism. I welcome him into the party fold,” Modi had said.

However, if party sources are believed, Jahangir was close to BJP long back. “He once led a delegation of Kashmiri businessmen, most of them being his friends, to Gujarat in order to influence Modi,” a senior BJP leader from Jammu, wishing anonymity, told Kashmir Life. “He along with PDP’s Muzaffar Hussain Baig enjoys a good relationship with former Intelligence Bureau (IB) director and now Prime Minister’s National Security Advisor Ajit Doval.”

The senior leader further revealed Jahangir’s “close association” with Peoples Conference chairman Sajad Gani Lone. “He was the man who facilitated pre-election communication between PC and BJP.”

In August 2014, Jahangir was appointed as official spokesperson of BJP in Kashmir. Born in 1976, Jahangir, basically a resident of district Ganderbal and now living in Srinagar, is the nephew of “infamous” police officer of Sheikh Abdullah’s time, Qadir Ganderbali. Before working as Special Correspondent for ARD German News Network, Jahangir “represented” Kashmir at many international platforms.

“Party had no alternative,” says War, while acknowledging the presence of some persons’ with “controversial past”, being detrimental to the party. War, who is now state-president Kissan Morcha, says after every election there is a restructuring where success is rewarded and failure thrown out. “It happened in this election too. Party leadership was misguided and tickets were given to undeserving candidates. But there will be a complete dry clean in March when the new leadership will take over,” he assures.

Till November 2013, Rafiqa Bilal was part of Socialistic Democratic Party (SDP) led by Darakhshan Andrabi. Andrabi, “known” for her Urdu poetry and “presence in army functions” fused her party with BJP. Hoping to get a ticket for Kulgam constituency on SDP’s ticket, her party patron Andrabi’s decision dashed her hopes. On the day of ticket announcement, Rafiqa, who contested 2008 elections on Panthers Party ticket, was not in the list. “They deceived us. I am not blaming party leadership but the regional in-charges, who sold mandates for lakhs of rupees. Those working for the last eight to ten years on the ground were sidelined because they had no money,” she says.

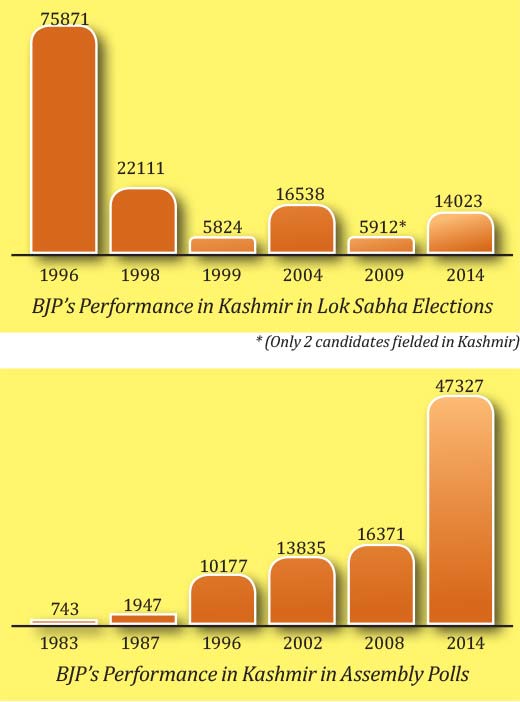

Prior to 1990s, BJP, much like 2014, had banked on Pandit factor, but it had failed to impress the Pandits then too. Post-1996, BJP has electorally, been more centric towards south Kashmir. In 1996, out of 13 candidates pitched across Kashmir, seven were from Islamabad, Shopain and Kulgam districts. Apart from the only candidate in North Kashmir, other five were from Srinagar and Budgam. BJP also made its Lok Sabha debut from Srinagar and Anantnag parliamentary seats in 1996. Remembered and criticised by many for the “role of army and counter-insurgents” to ensure participation in elections six year after governor’s rule, BJP’s two candidates – Sarla Taploo from Anantnag and Amar Nath Vaishnavi from Srinagar – took 75871 votes in aggregate in 1996 parliamentary polls, the highest number of votes BJP has taken ever from Kashmir.

In 2002, out of total 28 candidates from Kashmir, BJP fielded 14 candidates on the 16 constituencies of south Kashmir. During 2008 polls, 26 candidates from BJP were in a contest of which 11 were from four districts of south Kashmir. While party fielded the highest number of 34 candidates in 2014 polls, BJP had given the mandate in all seats except Rajpora. From 47,327 votes polled in BJP’s favour in Kashmir this election, south Kashmir gave 27,775.

With BJP sweeping to victory at centre, the party’s cadre in Kashmir has touched all-time-high in 2014. According to BJP’s War, around a hundred activists, who are doing party’s work day and night, is BJP’s Kashmir cadre. He also includes nearly 50,000 voters who cast the ballot in favour of the party in 2014 assembly elections in the party’s circle. On the other hand, Fayaz Ahmad Bhat says the party has 10,000 active members in the region. Independent estimates suggest around 28,000-member cadre of BJP and its arms worked in the recently held elections.

“Even if we have lost, people, whether out of fear or hate, came out in large numbers,” says Bhat. “This was possible due to the relentless efforts of party wings and other associates.”

One such wing, active in mobilizing voters in Kashmir, was Muslim Rashtriya Manch (MRM) of RSS led by senior Sangh leader Indresh Kumar. Weeks before elections, Kumar, whose name cropped up during Samjhauta blasts investigations, in a book launch function at Jammu said “the time had come for the people of Jammu and Kashmir, who have faced terrorism, discrimination and separatism to get industrialisation, education and Indianisation.”

Flanked by Subramanian Swamy, the erstwhile Janata Party leader who merged his party with BJP in 2013, Kumar equated 2014 assembly elections in Jammu and Kashmir with an “opportunity to revive ‘Kashmiriyat’ in the state.” During the function, he had remained silent on the issue of Article 370.

Comprising of a group of Muslim clerics from different schools of thought and aided by a “network of 800 NGOs and some 4500 workers”, the Muslim wing of Hindu RSS was trying to mobilize Kashmiri voters by asking them to “introspect on what will voting for a regional party yield for him?” The answer was provided by MRM itself: “Vote for Modi if you want a better future.” If sources are believed, dozens of MRM activists, before polls, thronged and camped in many assembly constituencies of Kashmir. Most of them were seen in south Kashmir.

Banking on Kashmiri migrant voters in pro-boycott constituencies of Kashmir, only 17 per cent of Pandit voters were driven to polling booths. Of 31,000 migrant voters, only 5169 came out to ink their fingers.

Notwithstanding the fact that all but one BJP candidate forfeited their deposits, the BJP’s strategy of finding Muslim candidates to represent a Hindu party in Kashmir didn’t bid well. Retrospectively, BJP had fielded only six Pandit candidates out of 28 in 2002 polls. During 2008, the number of Pandit candidates had gone to seven out of total 26 in the contest. However, in 2014 the number fell to five non-Muslim candidates when the party had fielded a highest number of 34 candidates in its history.

“If J&K can have a governor, police chief and other commissioner secretaries, all Hindus, why can’t it have a Hindu majority BJP government?” War asks.