With opening of new schools and mid-session transfers banned, Education Ministry is grappling with the ReTs, some of whom might have entered the system undeservingly. But the government will have to create new milestones to get its educational set up back on rails and monitor and encourage the private sector, reports Bilal Handoo

Far from the clamour raised by Rehbar-e-Taleem’s on city streets, education minister Naeem Akhtar is a sombre man sitting in his official bungalow on Srinagar’s power road, the Gupkar, attending an array of people. His lawn is dotted with people holding papers, documents and files. They have trekked miles to reach.

Among them is a retired Inspector General of Police holding a file, insisting for transferring his nearest kin. His request faces a polite refusal: “Mid-term transfers are banned and transfer industry is dead.” To another visitor Akhter says no new school can be opened. “But a possibility of a school closing in your vicinity can be located if there is a viability.”

II

But on face of facts, figures and features, the education mess, argue experts, is beyond a tough stand on transfers and halting the mushrooming of government schools. For them, the worrying trend in education remains the existing multi-level filtration through which students are made to pass annually. The end product of this filtration process finally takes refuge at state-run schools, breeding mediocrity, and perpetuating the same cycle.

It all starts with the first filter, full of zip, at the upper strata of society constituted by moneyed men known to send their children into elite schools to avail ‘quality’ education. “This is where education suffers from the first discriminatory shot,” believes Zubair Bhat, a senior private teacher. “This is not to say that such schools shouldn’t be there, but to say, it creates a vain competition among parents, who camp outside such schools for nights to secure entry form.” In the stage-II, they pay to get their kids in. “But then nobody questions this trend,” continues Bhat. “We seem to have made a perfect peace with it.”

Those not getting in the so called A-category, chooses the B-category and then the local Mohalla private schools. This is where the third filter comes into play. Those who fail to afford these three levels end up in Government School, forming fourth level. “So, the equation is clear,” says Bhat. “We are feeding the government schools with the residue of three-tier filtration.” Such students from low-income, illiterate and often disturbed family backgrounds need exceptionally great teaching to help them recover and make the best of it.

Since mainly lowest strata of society ends up availing government schooling, at least in the urban and sub-urban Kashmir, an invisible societal stigma is attached to it. There is a way out to end this stigma: Let every official, bureaucrat, minister and government officials send at least one of their kids in such schools. The quality of education could improve. But when former Panthers Party’s legislator Harsh Dev Singh brought a private members bill making it mandatory for all government officials to get their wards admitted in state-run school, he was scoffed at by his own colleagues in state assembly. Fundamental rights were invoked to oppose Singh’s idea! Later as Education Minister, he wrote many DO letters to various private schools to secure admission of his dear ones.

III

The lawmakers might disagree to agree on certain issue, but they can’t brush aside the fact – that other than life expectancy and income, education is an indicator of human development index, a measure of well being of the society. The importance of education, therefore, needs no reiteration. In Kashmir, the education is usually mapped and measured by literacy rate.

But J&K’s literacy scenario in no secret – in 2001, JK was 4th from the bottom when compared with Indian states and the situation improved only marginally in 2011 when state’s position changed to 6th, from the bottom.

Between 2001 and 2011, the literacy rate increased from 55.50 to 68.74 per cent but it continues to be below the 74.04 per cent, which is average Indian percentage. For this, the state blames on curriculum stagnation, paucity of Teacher Eligibility Test (TET) and uninterrupted recruitments.

However, to keep checks and cross-checks on education, the state has a juggernaut of an education department – the knowledge delivery system. It boasts of 143103 teaching staff, supported by 16668 non-teaching staff in a network of 24265 schools with cumulative enrolment of 16.68 lakh.

Even then, in the last 5 years, very few students from the Govt Schools have made it to the merit lists. For example, in Jammu province, only 4 persons in Class 10th summer zone figured in top 20.

IV

For this poor performance, the blame was also put on the two-level existing assessment system at class 10th and 12th. The commentators call it an “educational toothache”, which hurts the whole system through its waxing and waning rhythmic pangs.

“Till the time a child reaches class 9th and 10th,” says Mubashir Khan, a High School Govt teacher, “they are being bypassed from assessment. Once such student steps in Class 10, he is usually a tabula rasa (clean slate).” And to write on this “clean slate”, Khan says, a sword of Damocles often hangs over teacher’s head. “If the teacher fails to produce 33 pass percentage in his Class 10th,” says Khan, “he faces punitive action, including explanation and suspension.”

What Khan perhaps won’t tell for the fear of reprisals is: the assessment-free educational journey of a student from primary to secondary level is responsible for his overall ‘personality rot’. “That’s why in America and Europe,” he continues, “the major focus remains on primary schooling which, unfortunately, is being toyed in Kashmir.” Somebody asked the late APJ Abul Kalam, the former Indian President who recently passed away, Khan says, “How can we achieve corruption free society?” The missile man of India known for his vision 2020 had replied: “Only two persons can help us to achieve that – one parents and second, the primary school teacher.”

But in Kashmir (known for its massive corruption), Khan says, the primary school teachers even skip usual teaching. “And then they hide their incompetence and lethargy through tailor-made cent percent results, only to stay in the race of getting the best teacher’s award.” This truism indeed seems a serious dent to the official slogan: Our mission is to educate, employ and empower.

Interestingly, all this is happening in the society that 2011 census says is fairly young. The decadal data mining exercise reveals that the state has 2.01 lakh children below 6 years, while its 12.56 per cent populace is in the age group of 6-18 years. In other words, the census says, Kashmiri society is but youthful.

But often failing to ‘catch them young’, the youthful populace becomes the part of crisis by triggering alarming school dropout rate, believed to be the bedrock of educational mess.

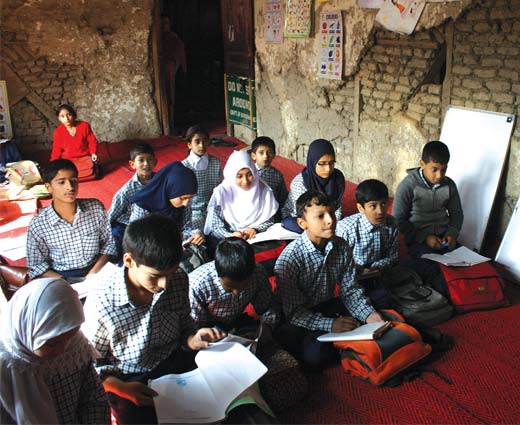

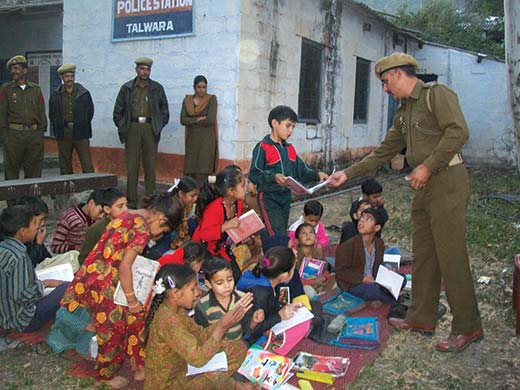

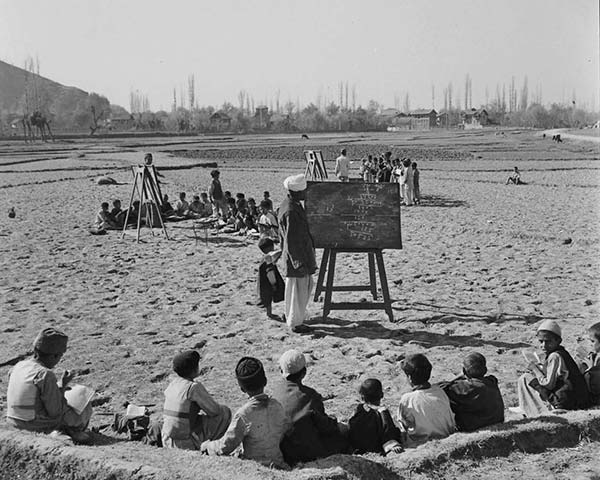

A multi-factorial trigger, including poor school infrastructure, no toilet facility, running school from rented rooms and poor family background is apparently fuelling this trend. The recent survey suggesting 38 per cent state-run schools lack drinking water facilities, while 26 per cent lack toilets perhaps leaves nothing for imagination.

“In Srinagar, mostly children of labourers and cart-pullers study in government schools,” Khan, the teacher, claims. “Some of these children are disturbed. And if sent to study inside rented rooms with no school-type feeling, they end up wrapping up their study.”

Statistics only support this assertion. From class 5th to 6th, the official figures say, the dropout rate is 6.24 per cent (against 4.67 per cent prevalent across India) and from class 8th to 9th, it is 5.24 per cent (against 3.13 per cent throughout India). Besides the survey Talaash conducted by the state in 2012-13 (the last known survey conducted in JK) makes this mess even more clear. Its finding says: 59061 children were out of school.

And since then, Khan believes, the number is only rising.

V

To revamp the education, the previous Omar regime had set up an expert group in 2013 to pave way to Education Policy, which continues to be stalled. Prof AG Madhosh, noted educationist and member of the group, had taken a serious note of school dropout rate at primary and middle levels.

“Schools have the best of the faculty but drop in enrolment is a serious concern,” he says. “Government rather than finding a solution to it is chasing after private schools.” The expert Group had observed little despotism, and lot of corruption in the education system.

Prof Madhosh, who himself runs many schools, says the expert Group had also recommended a set of reformative measures, including reconstruction of syllabus, change of examination system and inclusion of Kashmir history. But the recommendations were never implemented thus making the mockery of the whole exercise.

“Higher education in the state is a big mess,” he says. “If you want a corruption free society, quality-based productive endeavours you must encourage a focused privatization in education.”

VI

It is no secret that Kashmir prefers private schools known for their accountability and responsibility over government schools. Between 2008 and 2012, private schools admitted 621035 new enrolments (means 50.41 per cent students). To secure admissions in private schools, people are even ready to pay lakhs of rupees as admission fee besides hefty monthly fee. Even then, the much-talked about mess in private schooling remains the peanut salary being fed to teachers – even after putting up gruelling work hours.

Bulk of private admissions were done in Kashmir (57.68 percent) followed by Jammu (39.65 percent) and Ladakh (percent), as per the last census. Notably, students go for private schooling without caring for free lunches, free text books and free scholarships offered by government schools.

Sensing the same societal importance attached to private schooling, the present dispensation has called for formulating joint inspection system of JKBOSE and the School Education Department for recognition and affiliation of private institutions. A single window clearance system is being proposed to put in place to help ease the process of recognition for such schools.

This apparent shift of focus has set off speculations around with many saying: even government doesn’t seem to have much hope on state-run schools.

VII

But to give a desperate breakthrough to state-run education by addressing the prevailing mess, Akhtar visited JKBOSE’s Bemina head office lately. It was after 12 years that any minister was inside BOSE, a key institution. In that grilling session lasting for hours, he left the board members red-faced by pinpointed a goof up in textbook that oddly states: “Water from all natural sources is impure!” Like a tough headmaster, the minister tabled some hard facts before the board. Their incompetence was assertive enough from their dropped heads.

In that BOSE meeting, the minister eventually altered the mood when he asked officials to make textbooks available to students in digital format on official web portal for easy accessibility. But many fear that the proposal might not heal the board’s Achilles Heel, which remains its poor progress card. Result of the past few years in fact show that government schools pass percentage averages around 50 percent while that of private school is about 20 to 25 percent higher.

VIII

This poor result exist inspite of the fact the state allocating annual budget of more than Rs 6,000 crore for education.

Other noticeable mess in education remains its zero pass percentage—26 such schools only exist in Jammu. Many such schools running inside the abandoned kitchens and bedrooms rented out by people were approved by governments to generate employment. But of late, complains are piling up revealing how these schools manned by daughters or spouses of bureaucrats have turned into mere gossip and backbiting centres.

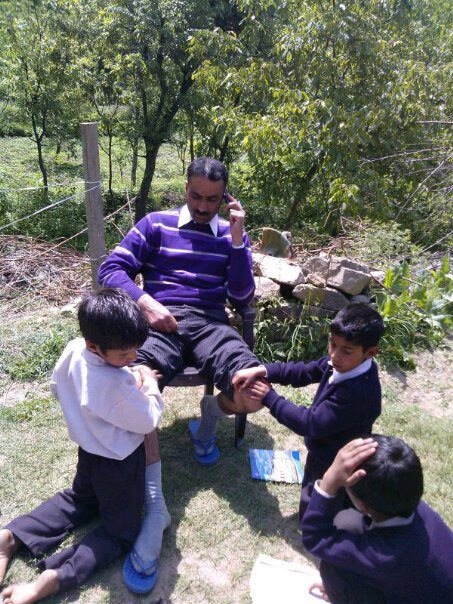

The mess often peaks public imagination and triggers loath when certain unpleasant instances unfold. In many cases, teachers were caught napping in their classrooms. Some were caught on camera forcing students to massage them, while a few were seen taken out by their teachers as labourers.

Though such instances are only a few, but they do cut a sorry figure for state-run schools, where, as per the unequal teacher-student ratio, not many are turning up with their satchels and lunchboxes.

IX

And now with the introduction of screening test, the discourse on state education is back to rhythm. While some ReT teachers facing the test argue, “society always needs a devil to curse and this time, it has chosen a teacher,” the experts say teachers must face the test to prove their skills. It is not a humiliation, they argue, as is being perceived by some. “Rather it is the easiest way to stay alive in completion.”

For most of these teachers, primary and secondary education is still an area to excel upon. Many say the present posturing of these levels of education is equivalent to a disaster. “I found most of the students of these levels quite genius,” says Dr Raja Muzaffar Bhat, a RTI activist, who teaches at Budgam government school for three days a week. “If imparted with proper teaching, they can excel like anything.”

Teachers must make their class interesting, he says, which will eventually motivate them to be regular in their classes. “Otherwise if subjected to dull teaching sessions,” he says, “such students who mostly hail from illiterate backgrounds won’t feel for their studies. And hence, they end up severing their educational ties.” With education suffering from multiple fronts, the mess it seems won’t be an easy task for state to clear.

X

At his official residence, a countryside man with henna-dyed beard hands over a paper to the state education minister. While scanning the document, the minister breaks into a deep smile, “so, you too have come with fake certificate of some teacher?” The man walks out and the minister asks his public relations officer nearby to put the certificate on a pile of documents resting at the corner of his office.

Before another person steps in, the minister breaks into a monologue: “Quite a mess to deal with…”