Systemic paralysis during militancy’s amorphous years in 1990s saw the closure of formal courts, ‘encouraging’ people to throng mobile informal courts. Safwat Zargar revisits certain verdicts and their implementation that helped romanticize the fugitive, albeit, for the time being

In the middle of 1990, a young Hizbul Mujahideen militant, Muzaffar Ahmad Mir from Kujjer, Kulgam, had “accidentally” killed two persons – a teenage girl and a boy – after a “misfire.” With almost every bit of the existing system falling under the shadow of armed groups fighting Indian rule, the victim families’ knew where the “justice” lay.

Days after the killings, the victims’ families approached the Hizb top command. Looked up to as an organisation where the teachings of Islam decided the course of things, it was an acid test for the pro-Pakistan armed outfit to demonstrate the implementation of the system, the group was fighting to establish. The affiliation of Muzaffar’s father, Mir Sonaullah with Jamaat-e-Islami, the cadre-based religious group known for its proximity with Hizb, turned the 21-year-old militant’s case in an unparallel rarity. At that time, Sonaullah was the district head of Jamaat for Islamabad (Kulgam and Shopain were part of Islamabad district then).

Negotiations were held. “Blood money” of rupees 1.25 lakh was offered to the victims’ families. During the course of “indirect” negotiations, on at least one occasion, the victim’s families were ready to accept the blood money. But that opportunity also failed. The families wanted blood for blood. By then, Muzaffar had appeared before the higher-ups of Hizb. He was disarmed and taken into the group’s custody.

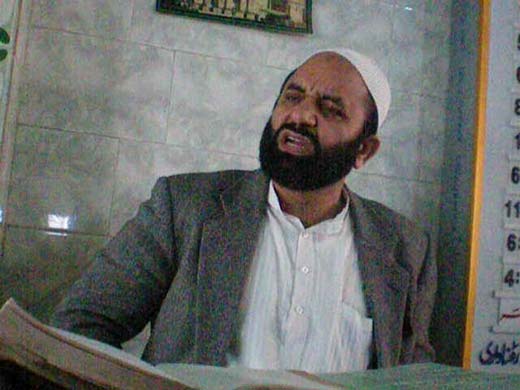

“It happened between 10 and 11 September in 1990,” says Sonaullah, while recalling the day when his son Muzaffar was brought home by the Hizb militants for the last time. “They came at around 11 in the night. Muzaffar along with his captors spent an hour with us. All of them had tea. He talked to his mother. The judgement for his execution had been announced around 20 days before. None of us had an idea that we were seeing Muzaffar alive for the last time.”

At around 12:15 PM the same night, some distance away from his home, Muzaffar was executed by the Hizb, itself. The group, during the “trial” of the case, had already told Jamaat top command about their decision.

Sonaullah, a retired government employee and long-serving member of Jamaat, led the funeral prayers of his son, next day. What he told the gathering of thousands after the prayers, lingered between pain and principles: “I accept Allah’s will. There should be no revenge or fighting. We have decided not to rake up this issue till the Judgement day.”

Twenty five years down the line, Sonaullah has kept his promise. He is still part of the Jamaat and is one of its basic members. According to him, he has never “regretted” what happened. A father of nine – seven daughters and two sons – Sonaullah, deeply religious and reserved, fails to hide the pain of a father who shouldered the coffin of his young son.

“Mea pushrov Khodayas, magar awlaad doad chu akhir rozwunui (I left everything to Allah, but still, the pain of a lost child persists,” he reiterates.

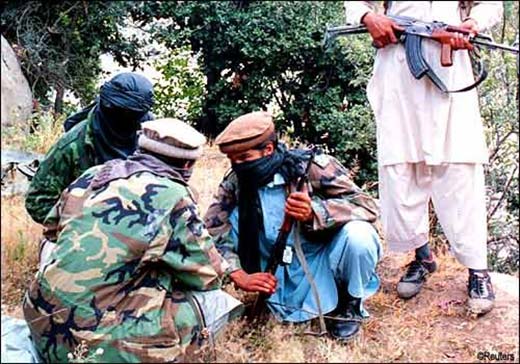

More than two decades have passed since Abdul Ahad Waza, a young pro-freedom supporter, crossed over Line of Control. One of the earliest commanders of Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), he vividly remembers the execution of one of the senior commanders of JKLF in Baramulla, ordered by the group. “It was a transparent system. If a member of the group was found guilty, the command council, after proper investigations and disclosure of evidence, gave the judgements,” he says.

“The top commander (name withheld) had done some mistake and he was shot,” Waza says. “JKLF owned the responsibility for it.” According to Waza, the system had different ways to deal with the armed fighters who crossed their professional line of duty. Disarming, beatings, social boycott, suspension, expulsion and imprisonment were widely used tactics in the group.

Thirty-year-old Fiza of Barzulla, Srinagar still has fresh memories of that evening in 1991 when she was playing with her friends at her friend’s place. “We heard shrieks. At that time I had no idea what it was about,” she says. Years later, Fiza comprehended the background of those shrieks.

“Basically, it was a court session of JKLF. The court-panel, which included some top commanders of JKLF, was hearing a case in which an upper-ground worker of the group was accused of sharing information with other armed groups. When it was proved, he was tortured by the members of group there only. They had made him drink water mixed with red-chilli powder,” Fiza says. “It was haunting.”

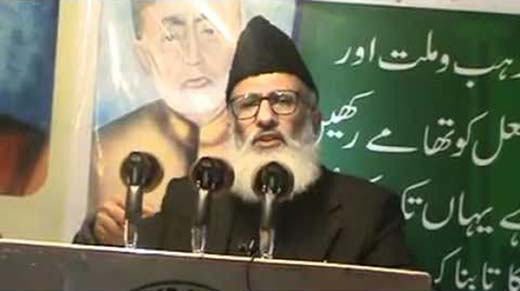

“Hizbul Mujahideen had a full-fledged disciplinary system under which the erring Mujahideen of the group were punished,” says Abdul Aziz Dar, alias General Musa, one of the early commanders of Hizbul Mujahideen. A member of Jamaat “since birth”, Musa, who served as a member of Hizb’s Markazi Shura from 1991-93, says “any group which had a sense of fear of accountability before God would never tolerate wrong actions of its members.”

Recalling the past, General Musa says, during 90s an injured ex-militant (name withheld) of Hizb was trying to secure a job at Kashmir University. “Due to his injury, he was no longer with us. When I came to know that he was using his past affiliation to leverage for the post, I kept him captive for five days,” says Musa, who was then District Administrator of the group in Srinagar.

In another incident, Musa and his men returned around 5.5 lakh rupees to the officials of a bank which was looted by some gun-wielding youth. In early 90s, when Musa came to know that X-ray machines and other medical equipments meant for SKIMS Soura, were looted by an armed group, his intervention facilitated the delivery of the machines to the hospital.

The justice and discipline system in Hizb worked in full coordination between militants and religious leaders, mostly from Jamaat, says Musa. “There was a proper hierarchy with designated powers to district administrators under whom different district level and sub-district level commanders worked. Hizb’s Shura Council followed the teachings of Quran in most of the complaints being heard by it but in many cases the organisation’s penal code known as Taazeer was also followed.”

“Mistakes did happen,” says Mohammad Azam Inqilabi, chief patron of Jammu and Kashmir Mahaz-e-Aazadi, “but there was a mechanism to rectify the wrong and stem the rot. Underground movements always have this fallacy. When the soldiers of formally organised and better equipped Indian Army are erring, it is very easy to guess how much hard it is to keep control on the activities of the thousands of underground armed fighters.”

“It is much easier to ensure discipline and proper behaviour in case of less number of fighters,” he says. “During early 90s, the mass populous support in favour of armed resistance actually resulted in the formation of dozens of groups. A 15-20 days training was not enough to educate and discipline a fighter properly. He was a crude guerrilla. At present, the number of armed fighters is very less as compared to 90s but the quality of a fighter, however less in number, is very high. While the armed resistance has now paved way for political institutions struggling for right to self-determination of Kashmiris, the justice and discipline system in armed organisations still exist.”

Forty-year old Mohammad Shafi, a resident of Sopore still remembers the public flogging of a Hizb militant by his own men near Arampora. “It was probably 92 or 93, a local militant alleged of having passed some unpleasant remarks at a girl, was whipped by his own colleagues on the directions of the Hizb chief commander Abdul Majeed Dar.”

Interestingly, while some of the militants, who had taken part in the public flogging, surrendered in coming years, the punished Hizb militant was killed in an encounter with the Indian paramilitary forces in 1995.

“I still remember that there were proper chargesheets and investigations against the accused,” says a former senior district commander of the Hizbul Mujahideen in south Kashmir, wishing anonymity. “There was a booklet named Taazeerat-e- Hizbul Mujahideen which contained detailed punishments and code of conduct for the members of the group,” says the former militant who is now part of Syed Ali Geelani led Tehreek-e-Hurriyat.

The senior ex-militant remembers how Hizb top command had ordered the killing of its “one of the stalwarts and a Hafiz-e-Quran” after the later had violated the group’s code of conduct. “The incident took place in 1994 at Chadoora Budgam. Hizb had ordered the ban on selling of Kashmiri Pandit lands and the slain militant (name withheld) had fired upon a person accused of violating the Hizb’s ban in which a woman was killed. His fault was that he had acted at his individual level. Despite protest from around 50-60 militants threatening to quit the organisation, the Hizb upheld its decision of killing the violator. After the killing, slain militants another brother joined Hizbul Mujahideen.”

In another incident, a Hizb platoon commander in Kupwara, who was found guilty of looting, extortion and harassing locals, was killed on the orders of Hizb. Similarly, in mid 90s, a kidnapping of a girl by a Hizb militant had compelled the group to launch a manhunt for guilty. He, too, was executed.

“There were some blacksheep in the outfit who when punished joined Ikhwan ranks immediately,” says another Hizb ex-militant, refusing to be named. “Many of those who were found guilty were working for their individual benefits and it’s them who tainted the whole outfit with their actions.”

Mohammad Ilyas, a government teacher from Kulgam, still remembers the atmosphere in government schools on Sundays in early 90s. Today, whenever he visits the Sadder Court complex in Srinagar, the rush of people along with their lawyers jostling around the court buildings puts him in the flashbacks. Ilyas’s memory is of Sharia Courts being held every week during the early years of militancy.

“Theses courts heard every kind of cases; from land and marriage disputes to property and offences,” Ilyas says. “It was an initial phenomenon of the armed resistance which stopped as soon as the Ikhwan terror unleashed.”

“The idea was to function as a parallel government,” says Umair Gul, a Kashmiri researcher at Nelson Mandela Centre for Peace and Conflict Resolution, New Delhi. “Hizb functioned like a state, or at least tried to. It interfered with the legitimacy of state through coercion and by setting up Sharia Courts; thus crippling the power of state over justice.”

Umair, who has done his Post-Graduation dissertation on comparative study of armed insurgent groups in Kashmir, says: “In the case of Hizb, judges were Jamaat-e-Islami functionaries but later as Jamaat became target of Indian agencies it was militants themselves deciding the cases. JKLF had the policy to function solely as guerrilla group, targeting intelligence mechanisms of the state but not interfere with justice question. Lesser known outfits like Allah Tigers interfered with marriage disputes while as Muslim Janbaz Force (MJF) and Al-Jihad did some policing but not substantial.”

A scholar, whose PhD research focuses on religion and armed conflicts, Umair, points out “at one point of time, however, as coordination committees were established between militant groups, there was a provision for parallel courts. But as the coordination broke down such courts also became irrelevant.”

Sharing one such incident of early 90s, General Musa remembers, one day while sitting with Hizb veteran Mohammad Abdullah Bangru, two boys of the group had come to meet Bangru. “The boys told Bangru about the family where they used to have meals regularly. According to the duo, the family had some marital disputes due to which the husband quite often beat his wife. When Bangru heard it, he immediately ordered the boys to bring the husband. I stopped them and told Bangru about the repercussions of using armed men in solving a romanticised relationship,” he says.

“As an elder, your intention should be to encourage warmth between the couple and not the discord,” Musa told Bangru. “He agreed.”

According to General Musa, the intervention of armed groups in “petty local and personal issues” was a “blunder” and the overall exercise had a “negative impact” on the armed resistance.

“One of the reasons for the group clashes was the judgements in the Sharia Courts as the implementing agencies for the decision were the militants. If a decision was given in favour of Mr A, the other party failing to comply with the orders of the court would approach another armed group; often resulting in confrontations.”

In fact, the group clashes had led Musa to enter into formal talks with JKLF in early 90s. Narrating the incident, Musa says, in 1992, he got directions from Hizb top command to meet JKLF leaders in order to ease out the tensions between two groups. “The meeting was fixed in Srinagar between me and Javid Mir of Liberation Front at one of the JKLF hide-outs. When I arrived at the spot, I was greeted by Zainul Aabideen, Spokesman of JKLF. He told me that Mir will arrive at 2 in the afternoon. I rebuked him that why didn’t they tell me it in advance. In the meantime, BSF had cordoned off the area and both of us were arrested.”

“That meeting never took place. I was released after thirteen years,” he adds.

In 2007, Police sources said a total of 757 factional clashes took place in Jammu and Kashmir since January 1990. As many as 679 people were killed in these clashes between various armed outfits including 506 militants, 173 civilians and 32 top commanders. According to the official sources, 102 militants and 347 civilians were injured in factional clashes till 2007.

On the other hand, former militant-turned-Hurriyat leader says the armed groups were trying to fill the vacuum resulting from the complete breakdown of state machinery including police and courts. “We were compelled to intervene,” he says, while recalling the incidents when “people used to cry and beg for the intervention of armed fighters in their disputes. It had a lot to do with the image and charisma of a young Kashmiri taking on single-handedly against the Indian state.”

What about the allegations of political killings of pro-freedom leaders against some armed groups?

“That was at the individual level,” says the former Hizb-militant-turned Hurriyat affiliate. “It was not done by the organisations but by some who had vested interests and worked against the struggle.”

Musa, on the other hand, feels all the major killings of pro-freedom leaders should be collectively investigated and truth be made public. “I will be the first one to support that move,” he says.

Back to Kulgam, many years later, Master Mohammad Ahsan Dar, the chief commander of operations for Hizbul Mujahideen at the time of Muzaffar’s killing, expressed his wish to meet Sonaullah Mir. He agreed.

“When Dar came, all of my family left their home and stayed at neighbours’ place till he left,” Sonaullah says. “I prepared tea for him. My family couldn’t bear his presence!”

Note: Some names mentioned in the story have been changed and withheld on request.

It is ironic that we often get swayed by pro-Jamat-e-Islami sentiments. Why don’t we mention how JeI or these Jamatis exploited their newly found power during 90s and how they became law unto themselves. And how they started enforcing their version of Islam (whatever that was)! We don’t have any issue if you glorify Jamatis, as long as you have courage to tell the world how they killed people just to implement their interpretation of Islam. I thank God that these Jamatis are done and dusted or else we would have been blasting mosques or rival ideologies by now and targeting each other in the name of GOD. The way these Jamatis used and misused GOD for their vested interests is a full fledged story. But then real stories never come out…or do they???