The dramatic abduction and release of an Israeli tourist in early nineties by the ‘powerful’ Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) on ‘humanitarian grounds’ might not have any relevance with the present day anti-Israel protests in valley. But as support mounts for Gaza in the Himalayan conflict zone, Bilal Handoo revisits the summer of 1991 to unfold the Israeli hostage crisis

Srinagar was rife with rumours in the summer of 1991. A word had spread that large number of Israeli soldiers masquerading as tourists had sneaked into the city. Many were discussing that Israelis have been requested by New Delhi to help army and paramilitary forces stationed in valley to fight the militants. Probably this rumour instigated the Pasdaaran-e-Inqilaabi-e-Islam (PID), a lesser known militant outfit, who soon created a sensation by abducting seven Israelis tourists from Srinagar.

It was no ideal time for tourism in Kashmir. United States had already issued an advisory to its citizens against visiting valley. Others followed Uncle Sam’s footsteps. But Israel was still dauntless. Soon a high profile attack on Israeli tourists in Srinagar shook Tel Aviv.

It was June 27, 1991 and seven Israeli tourists were staying in a houseboat called Garden of Heaven on the Dal Lake in Srinagar. Among these tourists was 23-year-old Yair Zion Yitzaki. He along with two Israeli girls was sitting around and playing cards. Around 11 PM, suddenly a group of militants belonging to the PID stormed the houseboat. Anticipating trouble, the Israelis crammed their pockets with knives and forks. But the militants after locking up houseboat owner Abdul Aziz Wangnoo and his staff in a room, forced the tourists on two shikaras and took them towards the old city of Srinagar.

Seven Israelis were then lined up in a small room in adjoining Saida Kadal locality, and asked to say goodbye to the two girls, Ella Burman and Alice Marlies. They were both released. But Israeli tourists were quite confident that having received military training back home, they could face the situation on their own.

One of them caught abductors completely unawares, jumped on them and snatched three AK-56 Kalashnikovs, four magazines and one hand grenade. There was a shootout in which one Israeli ex-serviceman, Erez Kahana and one militant were killed. While three other Israelis: Ali Maman, Yair Frisce and Yokov Shemesh were injured.

The wounded captives headed by their leader Hugagy Carbi barged into a local cleric’s house. In the mad rush, they started arguing with the family. But soon a reality dawned on them: They had lost track of one of their colleagues, Yair Zion Yitzaki! They kept the family hostage for the whole night. The next morning, as police arrived, they surrendered the three snatched AK-56 rifles at Srinagar’s police control room.

Later interacting with cops, the survivors said that Tel Aviv’s conscription policy helped them to overcome their abductors. They were soon flown out of India to Israel. But Yitzaki’s whereabouts were still unknown. A few days later, certain media reports made it clear that the untraced Israeli was with the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF). The militant organisation had kept him in their captivity for his safety “lest he could be killed by PID if they found him”.

Yitzaki was with JKLF for six days before he was handed over, strangely enough, to a local journalist then working for the Voice of America, Ghulam Nabi Khayal.

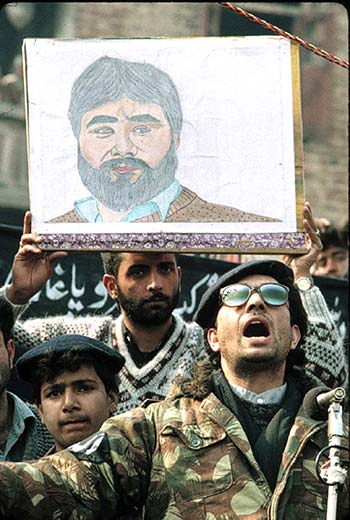

But before handing him over to Khayal, the then JKLF commander-in-chief, Javed Mir wearing beret and sun glasses, rang him up: “Look, we have rescued one Israeli tourist. We don’t want that the Indian armed forces to kill him and then blame us or other militants for the murder. So you better hand him over to United Nations office in Srinagar.”

Javed Mir, then 23-year-old young, fiery and confident militant commander dressed in faded jeans and an olive green jacket told Khayal that his boys found a trembling Yitzaki in a marsh (vegetable patch) in Saida Kadal near the shootout spot.

Twenty three years after the incident, time has taken its toll on Mir, now a member of Hurriyat Conference (M) headed by Mirwaiz Umar Farooq. He is no longer the de-facto supremo of JKLF and over the years, his macho image has waned. “By handing him over to UN, JKLF wanted to send a clear message to international community that we aren’t a terrorist organisation as we were being portrayed by India,” Mir told Kashmir Life after remaining tight-lipped about the incident for over two decades. “The aim was to tell the world that we were fighting for the right to self determination and the same should be acknowledged by all.”

But Khayal wasn’t ready to mediate when asked by Mir. “I advised him: ‘You should better contact the UN authorities yourself,’ ” Khayal says.

It was rather interesting when a simpleton in JKLF rank and file called the UN headquarters. He reached the radio officer Robert Mckee whom he mistakenly assumed as a senior official. Mckee told the guy: “Look, I could not leave UN premises without an armed escort.” This was unacceptable to the JKLF and for the time being, the matter hit the roadblock.

With a hunch that the militants were keen to gain some mileage by releasing Yitzaki as quickly as possible, Khayal agreed to approach the United Nations office. “I rang up Mckee and asked him whether he would accept the Israeli if he was handed over at a neutral place such as some hotel,” Khayal says. “I suggested that his armed guard could be posted outside the hotel during the handing over.”

But a Finnish official, Pekka Hannukkala, came on the line and told Khayal that they had strict instructions from the UNO New York headquarters “not to get involved”. But it was another matter if the Israeli was delivered inside the office compound. “In that case,” Hannukkala told Khayal, “he would not be turned away.”

Khayal then waited for a couple of hours at a pre-arranged place to brief the JKLF about what had transpired between him and the UN. They met in a houseboat where JKLF made Khayal to sign a “carefully-worded statement” admitting he had accepted Yitzaki and that the JKLF had released him to the UN authorities.

The JKLF negotiators had initially insisted on calling the entire press to the houseboat before the Israeli man would be taken to the UN office. “I vehemently turned down this suggestion as time was running out and I could not risk by taking out Yitzaki once the evening curfew was imposed,” Khayal says. “Moreover, getting the whole press involved in this messy incident seemed both dangerous and unfair.”

Finally, JKLF men agreed with Khayal’s views. And then on July 3 that year, Khayal went to JKLF hideout in the northern suburban locality of Soura, where the Israeli had been held in captivity. (Ingvar Oja correspondent of Swedish paper, Dagens Nyheter and a New Delhi based reporter, Shiraz Sidhwa who were in Srinagar, “requested” Khayal: if they could also accompany him to meet the Israeli hostage.)

“When I forwarded their request to JKLF, they were enraged about this lady because the same Sidhwa had done a concocted story against JKLF in a Calcutta-based magazine a few weeks ago,” Khayal recalls. However, JKLF had no objection to Oja who was in valley to cover the breathtaking developments taking place after abduction of two Swedish engineers of the Uri Hydel Power Project by Muslim Janbaz Force. “But Sidhwa forced her entry into my taxi and I couldn’t resist her move,” Khayal recalls.

However, Khayal says, Sidhwa was completely ignored during their hour-long stay at the dingy JKLF hideout. After some time, Khayal claims, he learned from a friend in Delhi that Sidhwa had most “unscrupulously” done the story for a magazine, taking “all credit” for Israeli captive’s release. “A few days later, the JKLF imposed a ban on Sidhwa’s entry into Kashmir,” Khayal says.

At about 6:20 PM, Khayal and Oja were escorted to a hideout and Yitzaki was handed over to them by a group of boys with whom he seemed to have become very friendly. “Yitzaki’s joy knew no bounds,” Khayal says. “He threw his arms around me when I told him that we had come to the take him home.”

But there was still a problem to be sorted out. Khayal insisted that Yitzaki must take off his JKLF T-shirt with “Down with Indian Imperialism” emblazoned on it. The JKLF men, however, were adamant that the Israeli could not leave without it. A few tense moments followed. But the better sense prevailed very soon. And they allowed Yitzaki to wear a new shirt. They gave him two identical JKLF T-shirts and asked him to promise that he would wear them once “he returned to Israel”. Yitzaki’s gifts included a copy of the book “Kashmir Bleeds” on human rights violations in valley.

At JKLF hideout in Soura, Khayal interviewed the captive: How did JKLF kidnapped him? “First of all I want to say that they [JKLF] did not kidnap me,” Yitzaki replied. “They acted so nice and they treated me as a guest. They would have set me free by now but they wanted me to be safe because some other militants group may have killed me.”

“Where did the JKLF find you?” Khayal asked him.

“They found me in a village. I was hiding there. They didn’t understand exactly what had happened to me. They tied my hands until I was handed over to chief of JKLF. They thought I was a commando. But they told me that they would not kill me,” Yitzaki replied.

Khayal then asked: “You are wearing a JKLF T- shirt, what have you been told about its activities?”

“I feel that I need to say what they told me to the rest of the world. Because otherwise the world will forget what is happening here. It’s unbelievable what I have heard. How can it be that in two years 10,000 people died here? How can security men rape a women and little girls? I am very angry with the Indian police and the Indian army. They knew one of us was killed and they knew one was missing. Why did no one come to search for me?”

Khayal says, Yitzaki was given a “touching farewell” with a number of women clapping for him. As Israeli left with them, he promised to come back when “peace returns to this beautiful place”.

As the taxi-ride culminated at the gates of UN office, Hannukkala met them in the lawns and photographs were taken to record the event. When asked if Yitzaki was absolutely safe now, the Finnish official replied: “He is as safe as we are.”

Meanwhile, Deputy Director-General in the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Moshe Yegar had flown to Delhi along with the unnamed Mossad agent. Later Moshe briefed the press, saying: “I conveyed a recommendation to Jerusalem to find the right channels to the Pakistan Government to send a message to the militants. I was convinced that Pakistan could contribute by telling the JKLF to let Yitzaki go.”

Later, Yitzaki was handed over to an Israeli diplomat in Srinagar and was then taken to the state guest house at Sonwar. “There Yitzaki was interrogated by the police,” Khayal claims. When he got to New Delhi, he did not say much to the media. But one newspaper quoted him saying about Kashmir journalist: “Maybe he [Khayal] was militant too.” But the Israeli had hailed JKLF. “I am telling you from my heart they [JKLF] were very kind to me,” he told journalists.

However, the JKLF action had further “alienated” it from other militant groups operating in the valley. The Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, the Dukhteran-e-Milat, the Mahaz-e-Islam and the PID accused all Israeli tourists of being spies visiting Kashmir “to help India weaken our movement”. While the Al-Umer Mujahideen called the decision to release the hostage a “hasty step”.

At late midnight, when Khayal returned home from UN office, he was told by his wife that throughout that night their telephone kept ringing without a hiatus. The callers, he was told, were as far as from Tel Aviv and Washington!

So whose side was JKLF really? or still is! Perfect timing KL by the way 😉