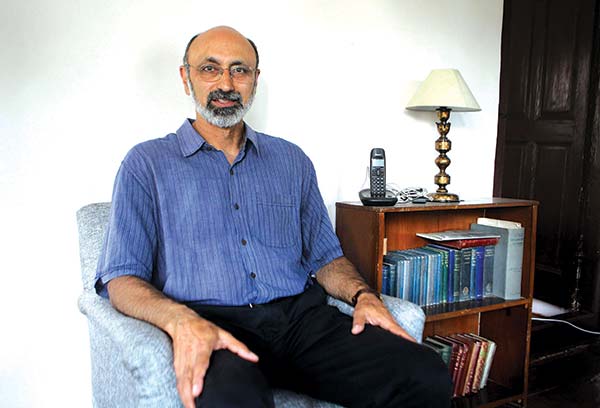

Suvir Kaul, the A.M. Rosenthal Professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania, describes himself as part belonging to, and part being an outsider to, Kashmir.

His father, who was one of the Kashmir’s first metallurgist, got a job in Bengal. This made Kaul’s family to shift there. Till his retirement in 1980, the family used to visit their house in Srinagar city’s Samandar Bagh area during summers only.

Kaul has always called himself a Kashmiri but he says that he never learned Kashmiri well even if his parents used to converse in Kashmiri.

However, in 1989, after the armed militancy broke out, Kaul’s family decided not to visit their house in Kashmir during summer. Kaul’s father was the only one who continued visiting his house for some more years. Kaul recalls his father’s visits stopped from 1993 to 2003 and no one visited the house in Kashmir. He remembers that time as ‘peak militancy’ era when entire Kashmir resembled one big army camp.

In 2003, when things relatively calmed down, Kaul visited Kashmir again, along with his mother and sister. He was surprised to find his ancestral house in Samandar Bagh area still in good condition. This encouraged him to resume visiting Kashmir during summers, particularly as his mother began to live here for those months.

Four years back Kaul’s father passed away. “He died at his home, on his favourite resting chair in Srinagar.”

Since 2003 Kaul visits his home in Srinagar for a month yearly. What he saw was disturbing:“It was quite painful for me in the sense that I consider myself an Indian and democratic. What I saw on the streets then was not democracy.”

After that visit Kaul started writing short pieces about the situation in Kashmir. His pieces were mostly about what he saw and witnessed in Kashmir during his summer visits.

During the same time he met Javed Dar, a Kashmir based photojournalist, whose work made Kaul think that these pictures are not getting representation in India. “I wished to inform a larger audience. Javed’s work left an indelible mark.”

Being an academician, Kaul believes that to understand a situation one doesn’t need to be physically there, reading books can be equally necessary. “That is why the first chapter in my book is titled as ‘Visiting Kashmir, Re-learning Kashmir’.”

The book is an account of how Kaul came to understand these histories for himself, combined with parallel accounts of what he was seeing here and changes he saw over time. Alongwith some local friends, Kaul began translating poems, in Kashmiri, poems that mediated upon the conflict. The poems used in the book are in Kashmiri because it is the language of daily conversation, preserves some of the immediacy of daily life.

Besides ‘Of Gardens and Graves’ Kaul, a specialist of English literature of 18th century in Britain has published three more books, Eighteenth-century British Literature and Postcolonial studies(2009), Poems of Nation, Anthems of Empire: English Verse in the Long Eighteenth Century (2001), and Thomas Gray and Literary Authority: Ideology and Poetics in Eighteenth-Century England (1991).

In an interview, Suvir Kaul tells Saima Bhat that literature keeps alive everyday memories of daily experiences which are crucial to understand the impact of long-drawn out of conflict.

KL: You left Kashmir long back so how do you relate with Kashmiri conflict, when you were not even part of those years?

SK: I never ‘left’ because, apart from visits, I had never lived here in the first place. And when you talk of the pain suffered by Kashmiris, you should not use we, for those only who stayed back. It should include those who left because they were equally traumatised.

This is why I have written this book to challenge the kind of question you have asked. Because that question rests on a single assumption that only Kashmiris who lived in the valley suffered. But the trauma of these decades is shared in ways that we do not allow credit for. I don’t want this book to sound as if it is a plea on behalf of Pandits. It isn’t. It is an account of what people have suffered here. And our questions have to be opened up to include that suffering of the displaced too. Otherwise the ‘we’ and the ‘they’ is exactly what the state wants us to believe in. Twenty five years of this will become fifty years of this divide.

Think what these poems are saying, being written by those who suffered here and those who have suffered elsewhere.

KL: ‘Of Gardens and Graves’ is a paradoxical title, isn’t it?

SK: Of course it is. It came from 18th century English poem, ‘The Deserted Village’ by Oliver Goldsmith, in which he talks about what capitalism was doing to rural agriculture and villagers in England. He said they are being thrown out of their homes. So he said England blooms but is becoming a garden on one hand and a grave on another hand. He wrote because he wanted people to pay attention to something that they were ignoring. That is what this book also wants to do. It is an attempt to draw the attention of people who normally don’t care about what is happening here. Not simply the sufferings of those who had to stay on but a larger political problem that involves displaced people.

It is not only the Pandits who left, I know a lot of Muslim families who chose not to live here or feared living here.

KL: Do you see Kashmir as a ‘Garden of Graves’ in a literal sense?

SK: I see it as juxtaposition. One of the phrases that I have used in this book is that ‘graves have flowered across the landscape’, which is true. If you look around there are more martyr graves than there were ever. They are not people who have died a natural death. So yes, that is partly the reason that the title is a paradox. But it is not my paradox, it comes from a poet who wrote in 18th century in England.

KL: How do you see the emergence of pro-resistance literature in Kashmir?

SK: Yes, there is lot of writing that is pro-resistance, but there is much writing that is simply about being tired and exhausted of political mobilisation and difficult lives. [Such situations even exhausted the leaders.] That is the spectrum of writing and we can’t expect it to be otherwise.

KL: Kashmir conflict dates back to centuries. How do you see the literal expression of people during different eras of conflict. How important is the preservation of literature in a conflict zone?

SK: The first part I can’t answer because I am not an expert on Kashmiri literature across the ages. About the preservation, it is enormously important. And nobody is doing it in Kashmir. This book includes a poem published in an Urdu weekly in December 2004, and one expects it should have been in libraries, in archives but it is not there. It has disappeared. I had two researchers who were hunting down for that copy but they couldn’t get it anywhere. It simply means it is lost. What is the point of saying we are pro-resistance when we cannot preserve the literature that is pro-resistance. We have forgotten what it means to build libraries and archives to preserve our own cultural productivity. In Srinagar I see everybody is building palaces but nobody is building libraries.

KL: How do societies in other conflict zones preserve their literary treasures?

SK: I have a very simple and vulgar answer. Functional libraries. Sometimes poems are conserved because they are sung. For example there is a poem of Bashir Dada in book which was recorded as a song and so lives on in peopl’s memory.

KL: You have used essays, poems and photos to tell the story of Kashmir, which is a new technique.

SK: Sometimes the shape of a book is result of a happy accident. In this case, when the book was going to be published I went to the publisher, Asad Zaidi of Three Essays Collective and I asked to choose a cover picture among thirty pictures by Javed Dar. I still remember that when I showed him a slide show, he became very quite. He is a poet and a sensitive man. At the end of the slide show he stopped and said ‘these are not only cover pictures but they need to be in the book’. I thought he may use four or five pictures only because it costs more money for a publisher to print pictures, but he used around 25 to 28 pictures. Javed’s pictures have enhanced the book considerably.

KL: Despite being one of the oldest conflicts in the world why hasn’t Kashmir produced a Mahmoud Darwish?

SK: Who says that Kashmir hasn’t? It took decades for Darwish to become a kind of well known figure internationally. He has been translated into many, many languages. Perhaps one of our Kashmiri poets is an important, but no one has done the kind of critical work that will allow us to see that.

Every Kashmiri scholar who is familiar with more than one language, must try to do his bit by translating the Kashmiri writings. This is the only way to present to people who read other languages our local poets and writers. If Darwish’s work would not have been translated in English and other languages, nobody would have known him except those who understand Arabic. Acts of translation are crucial, not only into English but in many languages. It takes the work of many people to allow a writer to achieve national or even global importance.

KL: How do you see Mahmoud Darwish in comparison to Agha Shahid Ali?

SK: I don’t want to make comparative comments. Agha Shahid Ali, Bhaya, was a friend of mine. I think he is a brilliant poet. I hope one day I’ll be able to write a book about him. He has almost become poet of Kashmir’s English speaking resistance. Interestingly most of Shahid’s work is not about Kashmir and he has several other volumes that people forget. They want to talk only about ‘Country Without A Post Office’, only. I have not met too many young Kashmiris who say that they have read his other books.

As a teacher, and as a friend, I want him to be celebrated for his entire corpus.

There are a number of other poets in Kashmir who have written powerful poetry. But they write in Kashmiri, and so few people including Urdu readers know them. And that is why I say translation in very important.

KL: Films are a good medium to record a conflict. Do you think Kashmir is neglected by both Indian and global cinema?

SK: Bollywood’s tryst with Kashmir has been disastrous so far. Besides, I don’t know of anything substantial done on Kashmir by Indian commercial cinema. Talking about Hollywood, that is part of America’s foreign policy, and they don’t likely care about Kashmir.

Yes, Aamir Bashir’s Harud was different, as were Moosa Syed’s Valley of Saints, Tariq Tapa’s Zero Bridge. But I haven’t come across any sensitive filmmaker from Bollywood who thinks hard about what is happening in Kashmir. The first half of Vishal Bhardawaj’s Haider was wonderful but the second half was commercial melodrama.

KL: It is said that people cannot afford to forget the conflict. Is literature a way to keep the past alive?

SK: 100 percent. Conflict is a very big term, it is an overarching term. Literature keeps alive everyday memories of daily experiences which are as important as large notions of conflict.