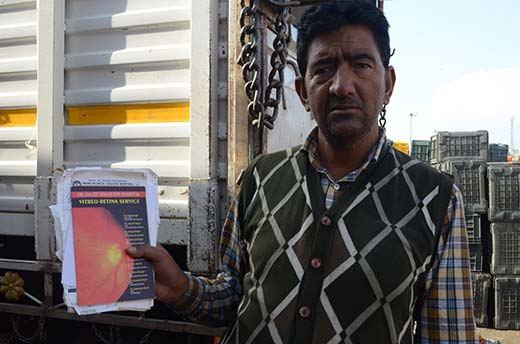

As ‘trucker’ Zahid Rasool’s immolation by Udhampur gangsters almost paralyzed Kashmir, people started talking in hushed tones about the nightmares that have remained part of transport sector’s unrecorded history. In the Fruit Market, these brave great men who are key to Kashmir’s survival and economy share stories of their survival within. Bilal Handoo took a day off, met a few of them to bring back stories of raw courage, never told before

The day NC lawmaker Abdul Majeed Larmi broke the news in state assembly about attack on Kashmiri truckers in Udhampur periphery, Javid A Bhat left his Bemina home for his routine eye check-up. The erstwhile trucker who lost the sight on the same ‘murderous’ highway seven years ago was later told by his family that some truckers were set afire, leaving two boys, Zahid and Showkat critical with burn injuries. The incident only refreshed memories of the nightmare of 2008 that doomed Javid’s once prosperous family.

Summer 2008 was sweltering for Kashmiri truckers plying on Srinagar-Jammu highway. As agitation broke in valley against Amarnath land row, the highway became a gory theatre of frequent loot and arson, assault and kill. The worst stretch was from Patnitop to Lakhanpur. Then, truckers recall, gangs of fanatics would appear from nowhere and intercept them with an intention to ‘slay’ them. Those truckers were returning valley with bagful of sob-stories, damaged trucks, broken bones and ruined lives.

“That was mob-lynching at its worst,” says Irshad Ganai, an Islamabad-based trucker who dreads to ply on Srinagar-Jammu Highway, the only connection between Kashmir and the rest of the world after 1947. “Since then, the mood often turns murderous for Kashmiri truckers outside Jawahar Tunnel.” The same mood has piled up a heap of miseries for Kashmiri truckers and their families, battling an inflicted health catastrophe.

Today, Javid, a proud trucker of yesteryears, is only undertaking an exhaustive foot journeys from home to eye-treating clinics. A shuddering incident that struck his life like a devastating thunderstorm seven years ago has rendered him unable to do anything in life. As he sits back inside his modest home in Bemina’s Hamdania Colony, a white substance begins oozing from his dazing eyes. Those eyes, his stack of medical prescriptions maintains, have lost almost 95 percent of their sight in the nasty attack while driving home on Highway one summer.

Then, it was the scary time to ply on Highway, he recalls. The air had madly turned communal in Samba in summer 2008. He along with his helper had decided that they won’t stop their truck till reaching Banihal. Behind the wheels, Javid was a desperate driver crossing Samba in speed. But before he could do that, a mob gathered on Samba Bridge threw stones at him. He didn’t stop. As he almost succeeded in leaving behind the mob, one razor-edged stone piercing through his truck and struck him on his right eyebrow. “Suddenly everything went black before my eyes,” says Javid, as his wife, two daughters hear a fresh narrative of pain, dropping their head inside a hushed room. After a few hiccups, he steers back his narrative.

The impact was heavy and dazing, Javid remembers, but he couldn’t lose the control of his steering. At a short and safe distance ahead, his helper took over the wheels, driving nonstop till Banihal.

At Highway town of Banihal, he was taken to a medico, who stitched up his open wound, but concealed a bitter truth. Throughout his journey back to Srinagar, the trucker couldn’t sense a faded eye-sight in his bandaged right eye.

Back home, his injury triggered a stream of tears before he was rushed to an eye-specialist who immediately referred him to Amritsar. “Even local doctors were unable to treat my injury,” says Javid amid silent and grim mood inside the room. Shortly a string of visits to eye-specialists outside ensued. But, nothing helped.

His family, however, kept going extremes. To sustain his medical treatment, they sold his two trucks. When that amount couldn’t help out, they then decided to sell their home. Even then his sight couldn’t be restored. With each passing moment, the family hit hard by the Samba attack was silently sobbing over the drastic twist of their destiny.

In the process, millions of rupees had vanished. But nothing proved effective. At last, the doctors revealed the ‘terrible’ secret, “there is no hope now!” The family did swallow a bitter pill, but just then Bhat’s left eye caught infection, which went on to diminish the eyesight of his only normal eye.

Inside Srinagar’s Parimpora Mandi, the truckers are narrating the harrowing highway accounts after Zahid’s killing. “We dread to ply on Samba, Kuthua and Udhampur highway – the stretch known to house anti-Kashmir tempers,” says Shabir Ahmad, a young trucker from Shopian. “While passing through these areas, we don’t slow down our trucks. Recently one of our truckers was ruthlessly beaten up there and all his money was looted. Those men out there are ready to pounce, hound us. Our hearts remain in our mouths and that’s why we often move in groups now.” He says these attacks keep no calendars. “Beef or no beef, they mount attacks even if they had a quarrel with their wives,” Ahmad insists. Police appear on the scene after the action is over, usually suggest driver to drive away fast, thus preventing legal course, which should have been a routine.

Going for long journeys is not the same again. These days, truckers kept receiving frantic calls from home to enquire about their safety. “After attack on Zahid and others, some of us have almost stopped plying on Highway,” Ahmad says. This hate campaign against Kashmiris seems sponsored than sudden and spontaneous – at least the boss of truckers sitting inside a well finished Parimpora office reckons that.

The hate for Kashmiris can only be imagined from the fact, says Bashir A Bashir, president Parimpora Fruit Mandi Association, that one of India’s top business group is also endorsing the anti-Kashmir sentiment. “Recently Adani Group ventured into fruit business,” says Bashir, a suave man with sombre facial expressions. “The company while taking their fresh fruit stock from Kashmir has shot a strict directive to dealers to omit the word ‘Kashmir’. This is height. They buy our stock without our name on it. One can imagine where from this hate campaign is stemming.”

It was the same hate frenzy against Kashmiris that forced a trucker to leave behind his truck and ran for his life from Udhampur to Banihal in summer 2010.

These days Abdul Hameed Khandey doesn’t take long routes that almost cost his life one night. This trucker from Srinagar’s Qamarwari, who is a lookalike of Bollywood actor, Anil Kapoor, still seethes over the episode that bled him to almost death. “It was perhaps in August that year when the mood had badly turned hostile for Kashmiris in Jammu province,” recalls Khandey, while unloading a fresh vegetable stock of his truck inside buzzing Parimpora Mandi. “There were seven of us, I mean seven truckers who suddenly were cut short by a gang of goons armed with hockeys, swords and sticks.” The next thing that followed, he recalls, was a murderous chaos.

Those hockeys, swords and sticks rained over them. “I saw one sword-borne youth mounting on my truck,” recalls Khandey, apparently visualizing those scenes with seething facial expressions. “He slammed his sword on my abdomen and cut it deep.” Khandey jumped from his truck and disappeared in darkness. He somehow managed to reach Banihal, where a doctor stitched his wound before continuing his hurtful homecoming.

But not all wounds inflicted by Highway have managed to heal.

A trucker from Old City’s Safa Kadal has been sitting idle in a rundown room of his medieval house from last seven years. The stay is maddening, yet his half paralysed body and sightless eyes aren’t encouraging him to step out. Before the mood inside the room turns dismal, Ali Mohammad Mata falters while recalling the nightmare, engulfing his and his family’s lives in darkness in summer 2008.

After returning from Delhi, he was caught by agitated mob in Kuthua that summer. After lynching him almost dead, the driver somehow managed to steer wheels again and reached Udhampur, where another shock was awaiting him. “I almost froze at the sight of another mob, waiting to pounce on us,” recalls Ali, as his wife, son and daughter crowd around him in a narrow room. “And then someone threw a stone that shattered my truck’s windshield before hitting me on his left ear.” The impact was horrific. He started bleeding from both his ears. His helper managed the steering and brought him back home, half dead.

The next few days were baffling. He would faint almost three or four times a day. The moment he consulted the doctor, he was diagnosed with severe concussion that had also impacted eyesight of his left-eye. To restore his sight, he sold his share in a truck he was driving. But the frequent visits to Amritsar and AIIMS subsequently left him cash-strapped. After finding himself caught between poverty and poor health, Ali developed multiple ailments, including strokes, hypertension, diabetes, arthritis among other things.

Back home, his wife started spinning wheel, while his daughter started tutoring in private school. “Even then,” he says, “things became bad to worse.” And then came a bright moment. His son, Omar secured the PM Scholarship (PMSSS) that landed him in a Chandigarh’s engineering college, where he was finally shown door due to his inability to pay his tuition fees. “My father’s monthly medical bill is around Rs 2000,” says Omar, looking anxious. “I don’t know how we are going to manage all this.” Omar’s dilemma is that he is unable to decide whether to carry his studies amid poverty or start earning. His sister, Zeenat is finding herself in the similar predicament. “No help is at the horizon for us, even our MLA Mubarak Gul turned us down,” Ali says. “There was a time when I used to feed around 10 people, but now, we hardly meet two meals a day.”

Many such tormenting narratives revived after Zahid Bhat of Bijbehara’s Batengoo village lost his life in a communal frenzy. Most of the narrators continue to face arson and loot outside Jawahar Tunnel. “Only in summer 2008, around 60 to 70 percent truckers would return valley with badly damaged trucks,” says Amir, a young Shopian trucker. Between August 14 and 22 that year, 122 in-coming trucks returned valley with damaged windshields, records indicate. Sensing the gravity of the situation, authorities then replaced the broken shields of 17 trucks and then ran out of stock. Then, remembers a police official posted at Lower Munda, trucks with damaged windshields would trigger panic and a mess in Kashmir. Kashmir, Chenab and Pir Panchal Valley’s and the entire Ladakh region were suffering because of economic blockade.

In the same year, Shopian shuddered when three of its sons turned truckers were brought home with severe burn injuries. Sajjad Hussain Mir, Abdullah Mir and Bashir Mir were admitted in a Jammu hospital after a mob tried to burn them alive on Highway near Jammu touching Punjab border. “When those three truckers were still battling for their lives, another trucker Muhammad Lateef of Bemina Srinagar was shifted to PGI Chandigarh for treatment in a critical condition,” Amir says. Lateef was attacked by rioters at Lakhanpur who threw petrol bomb inside his truck.

The stretch between Lakahnpur and Udhampur, of late has become safe haven of a gang of arsonists, who many believe want to repeat 2008 economic blockade or what Syed Ali Geelani calls “economic terrorism”. The truckers recall that threat mostly stems from hundreds of Sangh Parivar activists in Jammu. “Vehicles ferrying Shiv Sena, Bajrang Dal and Vishu Hindu Parshid activists are moving in only to hound,” says Amir. “Armed with sticks, tridents and other sharp edged weapons, they shout anti-Kashmiri before pouncing on us.”

Most of these attacks are being orchestrated after the word being spread that Kashmir-bound truckers carry bovines. “This gives them a license to target the truckers,” says Bashir, president Parimpora Fruit Mandi. “Like in May 2013, when some goons set on fire a Kashmir-bound truck after spreading a word that the truck carries bovines.”

Post partition, Kashmir’s access to the rest of the world shrunken to just this highway. Though initially it was being taken care of by the state government but when traffic surged with the passage of time and the condition of the road deteriorated, Border Roads Organization took over.

In absence of rail, Kashmir solely relies on trucks, for transporting everything in and out of the Vale and the Highway continues to be one. Of around eight thousand vehicles that pass the Jawahar Tunnel a day, more than half are trucks. As the government is planning improving this road and making it better, it is the security of Kashmir bound traffic that is the emerging key concern.

For reaching Srinagar, there are many options. One can crossover through Kishtwar and Sinthan road, even Mughal Road is not a bad idea, or the new highway that will take off from Bani and reach Bhaderwah and then cross through Sinthan. But all these roads pass through the same sensitive belts that pushed Kashmir bound traffic to the receiving end. With north pole-south pole alliance in power, there could be instances which could surcharge the situation. Authorities may have to improve security on the road well before other options are discussed.

Oblivious of the debate about the roads and the situation, Javid, the blinded trucker continues to live a miserable life at his Bemina residence. In not so distant past, locals brought him home, his body drenched with filth. One of his rescuers while giving him a shoulder informed his family: “He had mistakenly stepped onto an open drain.”