Faith-healers, astrologers, Pirs, Fakirs and Gurus have traditionally remained unofficial advisers and courtiers of rulers in Indian subcontinent before and after partition. Kashmir’s last monarchs were greedy and superstitious and they also had one. Historian and author Khalid Bashir Ahmad details Hari Singh’s Rajguru who sold dreams of independence to him but was infamous for the company of women

Maharaja Hari Singh, J&K’s fourth generation Dogra ruler, was known to be in favour of independence instead of joining the dominion of either India or Pakistan. It has been argued that he was opposed to communal politics of the Muslim League and equally loathed the Indian National Congress particularly for its propinquity with his nemesis, Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah. Was that the only reason behind his aspiration to see J&K as an independent country or was there something more to it?

Hari Singh’s desire to rule a sovereign country once the British had departed from India was deep rooted and independent of his alleged aversion to Jawaharlal Nehru and Muhammad Ali Jinnah. His idea of independence “was not a democratic country where people would be powerful but a monarchy where he himself would wield absolute power.”[1] He was feudal at heart and not happily disposed to British suzerainty.

In fact, the ruling dynasty had a longing for total independence ever since the overbearing British interference into the affairs of the largest princely state. The diminution of Maharaja Pratap Singh, Hari Singh’s predecessor and uncle, to a show-piece ruler after his alleged hobnobbing with the Czar of Russia had not gone well with the dynasty. The departure of the British from the Sub-continent was an opportunity for Hari Singh to realize his long cherished dream and he wanted to seize this opportunity.

When the British paramountcy lapsed and India and Pakistan became sovereign countries, Hari Singh saw independence as “an active option”.[2] He grabbed the opportunity and refused to listen to Nehru, Mountbatten and Jinnah until he was forced by circumstances and individuals into signing the Instrument of Accession after remaining ruler of an independent country for two months. The Maharaja had sent Mountbatten to a south Kashmir village near Mattan for fishing when he came to Srinagar on June 18, 1947 to discuss the question of J&K’s accession and feigned illness to avoid a meeting with him on the subject next day.

There were quite a few people, apart from Prime Minister Ram Chandra Kak, who had fuelled Hari Singh’s desire to be an absolute ruler of an Independent country. Among them, Rajguru Swami Sant Dev was the foremost. He was a non-state subject about whose native place nothing is known even as it was believed by some that he had been planted in the palace by the British Government.[3] He had arrived in J&K during the time of Maharaja Pratap Singh who, being a very superstitious person, had assembled a number of Hindu swamis (priests), astrologers and gurus (spiritual guides) round his court.

The Swami had convinced Hari Singh that luck was smiling at him and that he would become the sovereign of “an extended kingdom sweeping down to Lahore.”[4] This had stoked the desire of the Maharaja to remain independent rather than joining India or Pakistan at the time of the Partition. He believed that he could build a new kingdom which some called ‘Dogristan’[5] and had ‘at great cost’ prepared a new crown of diamonds and emeralds for his coronation as ruler of this new kingdom.[6]

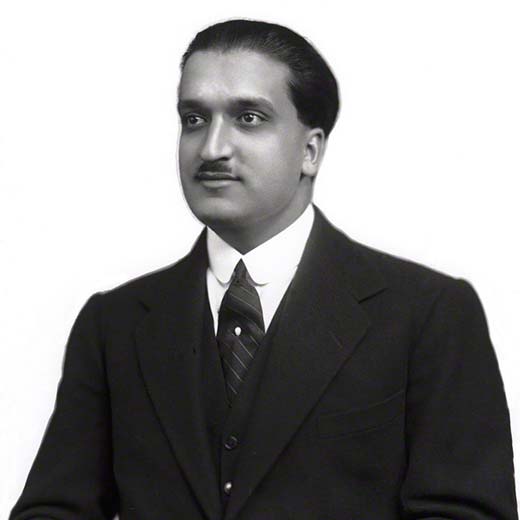

A tall, handsome and well built pink-complexioned man even in his advanced age, which he would actually never reveal, the Swami was known as the Rasputin of the Court of Kashmir[7] who loved the company of women and took opium regularly. (Rasputin was a Russian faith-healer who exercised significant influence on Czar Nicolas II and his wife, Alexandra Feodorovna, and was considered to be responsible for their downfall.) The Swami was a prototype of the present day ‘god-men’ who exercise considerable influence over the minds of some of the top politicians of India[8] – ala Dhirendra Brahmachari. The royal ladies would visit him for his darshan.[9] Once, he was reported against by a British woman, Mrs Berk who lived nearby, for making passes to her young daughters upon which he was asked to leave the State for some time.[10]

The Swami had risen to the position of Rajguru (chief spiritual guide of the Maharaja) during Pratap Singh’s rule and was rumoured to have great spiritual powers. He used his position to ensure a firm grip on the Maharaja who in turn gave him full state protocol. The Maharaja would issue orders under his own signatures instructing authorities to make special arrangements for the Swami whenever he visited some place. Addressed in official communications as Swami Sant Dev Ji Maharaj, when he reached Jammu on May 14, 1925, Pratap Singh issued an order a day earlier for a motor car to “meet him at the Railway Station”[11] and when he visited Achhabal that year the Maharaja directed his Foreign Department to “make all arrangements for Farash Khana and Farashes as in the past” for the Swami.[12]

On the demise of Pratap Singh in 1925, fortunes of Swami Sant Dev changed for worse. An agnostic Hari Singh, after ascending the throne banished from his presence the swamis and gurus, including Sant Dev, collected by his uncle although as the spiritual guide of the predecessor Maharaja he had sanctioned life-time Mukarari (grant) of Rs 300 per month in his favour on December 5, 1925.[13]

After about two decades, Sant Dev made a mysterious comeback in 1944 and by 1946, had firmly ensconced himself again as the Rajguru. He was installed by Hari Singh in the Cheshma Shahi Guest House[14] or the present Raj Bhawan, originally built by the Maharaja for his consort, Maharani Tara Devi. From May 1946 until October 1947, he was always in residence in various houses within the palace compound in Srinagar.[15]

Meanwhile, Tara Devi, the “warm and gregarious”[16] fourth wife of Hari Singh and the only to bear him an heir, had taken full control of the palace affairs since 1945. She was under the “overpowering influence”[17] of the Swami who in turn used this proximity to extend his influence on Hari Singh. The Maharaja, to the amazement of everyone including his son, became a devout disciple of the Swami, sat on the ground before him for long hours and never smoked in his presence. He also gave him many gifts and amenities, including costly silk robes and a car.[18]

The dream of Hari Singh to rule a sovereign and independent J&K was, however, shattered by subsequent developments, which saw him under pressure from the Indian State and its leadership to decide on the Accession. This included visits by Mahatma Gandhi and other senior Congress leaders, besides mentoring by RSS Sarsanghchalak, Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar, who was specially flown to Srinagar on October 18, 1947 by Indian Home Minister, Vallabhbhai Patel, to persuade Hari Singh to acceded to India.[19]

The Tribal attack on Kashmir dramatically changed the situation, forcing the Maharaja to flee from Srinagar on October 27, 1947 in the dead of the night. When the convoy reached Kud, 100 kms from Jammu, a cream coloured car joined the procession. Seated in the car was Rajguru Swami Sant Dev Maharaj whose miraculous powers, recalls Karan Singh with sarcasm, did not include facing the Tribals.

As the curtain on Hari Singh’s dream of independent J&K was drawn, he “had come to realize that the Swami’s pretensions to great occult powers were somewhat over-rated, and his old scepticism had begun to reassert itself.”[20] Subsequently, he had released himself from the influence of Swami Sant Dev. The Swami was one among many influential persons close to the palace accused of instigating large-scale violence against Muslims in Jammu. He was strong supporter of the RSS in J&K.[21]

Hari Singh remained a titular Maharaja of J&K up to 1949 when he was ultimately forced to abdicate in favour of his son, Karan Singh, and asked to leave J&K along with his wife. He shifted to Bombay (now Mumbai) and died a sad man there on April 26, 1961, separated, as he was, from his wife who after leaving Jammu had returned to her native place in Himachal Pradesh.

[1] Krishan Dev Sethi in a telephonic interview with the author on November 9, 2014.

[2] Victoria Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War, p

[3] Krishan Dev Sethi in a telephonic interview with the author on November 9, 2014.

[4] Karan Singh, Heir Apparent : An Autobiography, Oxford, 1989, p 37.

[5] Kwasi Kwarteng, Ghosts of Empire: Britain’s Legacies in the Modern World, p 121.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Shiri Ram Bakshi, Kashmir- Valley and its Culture, p 251; Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah, Aatash-e-Chinar [Gulshan], p . 311.

[8] Jagmohan, My Frozen Turbulence in Kashmir, p 84.

[9] Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, Aatash-e-Chinar [Gulshan], p 311.

[10] Ibid.

[11] File No. 283/V-7 of 1925, Archives Repository, Jammu.

[12] Ibid.

[13] File No. 163/130G/1926, Archives Repository, Jammu.

[14] Karan Singh, Heir Apparent : An Autobiography, Oxford, 1989, p 37.

[15] Kwasi Kwarteng, Ghosts of Empire: Britain’s Legacies in the Modern World, p 121.

[16] Karan Singh, Heir Apparent : An Autobiography, Oxford, 1989, p 5

[17] Sati Sahni, A Conversation, (http://ikashmir.net/pakraid1947/sahni2.html)

[18]Karan Singh, Heir Apparent : An Autobiography, Oxford, 1989, p 37.

[19] Tapan Bose, Kashmir Times, September 1, 2014, (http://www.kashmirtimes.in/newsdet.aspx?q=36234)

[20] Karan Singh, Heir Apparent : An Autobiography, Oxford, 1989, p 55.

[21] Shiri Ram Bakshi, Kashmir- Valley and its Culture, p 251.