International human rights watchdog Amnesty International released its latest report on July 1, 2015. The report focuses on the use and abuse of AFSPA in denying justice to the victims of the violations of human rights for the last 25 years. Given the public interest attached with AFSPA and the issue of justice, Kashmir Life is reproducing the entire report for its readers

BACKGROUND

The last time 17-year-old Javaid Ahmad Magray’s family saw him alive, he was studying in his room. It was late on the evening of 30 April 2003. When they came downstairs the next morning, Javaid was gone.

His father Ghulam Nabi Magray saw a few army personnel standing at the gate outside, and told them that his son was missing. They said, “Don’t look for him, go back inside.”1 But down the road, Ghulam Nabi and his wife Fatima Begum could see bloodstains and a tooth lying on the pavement. Soon after, their neighbours gathered. When they saw the bloodstains, they immediately began shouting and protesting, demanding to know Javaid’s whereabouts.

During the investigations that followed, Ghulam Nabi testified that the officer in charge of the army camp at Soiteng had told them that Javaid was in the Nowgam police station. The family had rushed to the police station, only to be told that Javaid had been brought there at about 3 am but was then taken to Barzalla Hospital, then shifted to SMSH Hospital, and finally to Soura Medical Institute, where he was declared dead.

An officer at Soiteng testified during investigations that Javaid Ahmad Magray had been wounded in an encounter with some security force personnel, and was taken to Nowgam police station and later to a hospital, where he succumbed to his injuries.3 The chief [Station House] officer of Nowgam police station testified that the same officer of the Assam Regiment, “on May 1 2003 at 2:30 am came with a written application that their party was on patrolling of the area and at 00:30 hours [one militant was wounded] while three others taking the benefit of heavy rains and darkness succeeded in running away.”

The police registered a First Information Report (FIR) and sent Javaid Ahmad Magray to hospital. They also testified that the police station had no record that Javaid Ahmad was involved in “anti-national activity or militancy.”

Relatives and neighbours of Javaid Ahmad Magray, his teachers, and representatives of the army and police all took part in the inquiry into his death carried out by the district magistrate. The report concluded that the army’s version of events was false, and that the “deceased boy was not a militant…and has been killed without any justification by a Subedar [a junior commissioned officer in the Indian Army] and his army men being the head of the patrolling party.”

According to the district magistrate’s report, the Subedar left Srinagar and failed to respond to official summons to record his statement for the purposes of investigation. The army, in a letter to the magistrate, said that the Subedar’s unit had been moved and suggested that further correspondence should be sent to another army address. A subsequent letter duly sent was returned undelivered after sixteen days.

In a letter dated 16 July 2007, the Jammu and Kashmir (J & K) State Home Department wrote to the Joint Secretary (K-1), Ministry of Defence in Delhi to seek sanction to prosecute nine army personnel against whom the state police had filed charges of murder and conspiracy to murder for Javaid Ahmad Magray’s death. The letter stated that “the deceased was a student and was not linked with militancy. He was killed by Assam Regiment after kidnapping. The case registered by the Assam Regiment against the deceased [as a “militant from whom arms and ammunition was recovered”] has been closed as not proved.” The letter requested the Ministry of Defence to “kindly accord sanction of prosecution as is envisaged under section 7 of the Jammu and Kashmir Armed Forces Special Powers Act, 1990 against the accused Army officials.”

Ghulam Nabi knows that the case was sent for sanction – or official permission to prosecute the security force personnel – under the AFSPA in 2007 but says he has received no information on the outcome of the application. “We simply never heard what happened with it,” he told Amnesty International India. A Ministry of Defence document dated 10 January 2012 simply states that sanction for prosecution was denied on the mgrounds that “the individual killed was a militant from whom arms and ammunition was recovered. No reliable and tangible evidence has been referred to in the investigation report.”

Sanction to prosecute is recorded as having been denied on 3 January 2011, three and a half years after it was sought by Jammu and Kashmir authorities.8 Ghulam Nabi and his family were never officially informed about it.

“The problem is that the army never accept that sometimes these violations happen. They’re always in denial,” Ghulam Nabi said.

Javaid Ahmad Magray is just one of hundreds of victims of alleged human rights violations committed by security force personnel that Amnesty International and other organizations, both local and international, have documented in the course of the past 25 years in Jammu and Kashmir. The words of his father reflect the frustration and despair felt by many families across the state at the refusal of the Indian authorities to hold to account those responsible for serious human rights violations.

Indian security forces have been deployed in Jammu and Kashmir for decades, officially tasked with protecting civilians, upholding national security and combatting violence by armed groups. However, in the name of security operations, security force personnel have committed many grave human rights violations which have gone unpunished. The failure to address these abuses violates the rights of the victims and survivors to justice and remedy, which is enshrined in the Constitution of India and international human rights law.

The violence in Jammu and Kashmir has taken a terrible human toll on all sides. From 1990 to 2011, the Jammu and Kashmir state government reportedly recorded a total of over 43,000 people killed. Of those killed, 21,323 were said to be “militants”,10 13,226 “civilians” (those not directly involved in the hostilities) killed by armed groups, 5,369 security force personnel killed by armed groups, and 3,642 “civilians” killed by security forces. Armed groups have committed thousands of abuses. 12 In general, victims of human rights abuses in the state have been unable to secure justice, regardless of whether the perpetrator is a state or non-state actor.

Shocking as the government statistics are, human rights activists and lawyers say that the figure of civilian deaths caused by the security forces fails to reflect the true scale of violations by security forces. Activists estimate that up to half of all human rights violations by security force personnel may have gone unreported in the 1990s and early 2000s.13 Amnesty International reports in the early to mid-1990s documented a large number of instances of torture and deaths in custody of security forces.14 This organization alone recorded more than 800 cases of torture and deaths in the custody of army and other security forces in the 1990s, and hundreds of other cases of extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances from 1989 to 2013.

Amnesty International’s research over a number of years has repeatedly uncovered patterns of impunity, including unlawful government orders to the police not to register complaints of human rights violations against the security forces.

One of the primary facilitators of impunity for security force personnel has been the existence of provisions like Section 7 of the Armed Forces Special Act (AFSPA), 1990 under which members of the security forces are protected from prosecution for alleged human rights violations. Similar to clauses in a number of other Indian laws, this legal provision mandates prior executive permission from the central or state authorities for the prosecution of members of the security forces. These provisions, called “sanctions” in India, have been used to provide virtual immunity for security forces from prosecution for criminal offences.

To date, not a single member of the security forces deployed in Jammu and Kashmir over the past 25 years has been tried for alleged human rights violations in a civilian court. An absence of accountability has ensured that security force personnel continue to operate in a manner that facilitates serious human rights violations. A former senior military official publicly argued in October 2013: “Immunity under AFSPA allows our soldiers to make mistakes. Insurgency will come to an end, you need to train soldiers better, I agree, but don’t remove the AFSPA.”

Following a visit to India in March 2012, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions expressed concern that sanction provisions in India “effectively render a public servant immune from criminal prosecution… It has led to a context where public officers evade liability as a matter of course, which encourages a culture of impunity and further recurrence of violations.” These fears are well founded.

Despite assurances from the Chief of Army Staff and the Head of the Army’s Northern Command in December 2013 that there is “zero tolerance” for human rights violations by the army, more than 96% of all complaints brought against the army in Jammu & Kashmir have been dismissed as “false and baseless” or “with other ulterior motives of maligning the image of Armed Forces.” The small number of cases in which complaints against personnel have been investigated and military trials conducted are closed to public scrutiny. Few details of investigations conducted by the security forces are available to the public. The military are notoriously reluctant to share substantive information about how they conduct inquiries and trials by court-martial into human rights violations. There is even less information publicly available about investigations and trials conducted by paramilitary forces.

“A number of complaints of human rights violations against the Army are found to be false and instigated by inimical elements…such complaints are aimed at maligning the Army and embroiling it in legal tangles and provide ripe fodder for various human rights activists and separatist organizations to subvert the minds of the general population,” Human Rights and the Northern Army, Indian Army Headquarters Website, Human Rights Cell.

With the continued existence provisions and like enforcement of legal AFSPA, access to effective legal remedies for victims of human rights violations and their relatives in J&K remains as limited today as it was in the 1990s.

Families interviewed in 2013 say that positive measures such as an increase in the number of police stations, the establishment of the Jammu & Kashmir State Human Rights Commission in 1997, and increased stability in the region, have made it easier to report human rights violations in recent years.

However, while the criminal justice system may have become more accessible in comparison to the 1990s and early 2000s, Amnesty International India’s recent research reveals how even the slow journey towards justice in a few cases is undermined by the government’s recourse to legal provisions to shield members of the security forces from prosecution at any cost, and a military justice system that fails to hold its personnel accountable for human rights violations.

This report seeks to expose the government’s complicity in facilitating impunity for security forces in Jammu and Kashmir, and challenge the de jure and de facto practices it uses to block justice for victims of human rights violations.

This report challenges the use of sanction provisions under the AFSPA; demonstrates how the denial of sanction or permission has been routine and entirely lacking in transparency; and argues that the continued use of the AFSPA violates India’s constitutional guaranteed rights to life, justice and remedy. By not addressing human rights violations committed by security force personnel in the name of national security, India has not only failed to uphold its international obligations, but has also failed its own Constitution.

This report also documents how legislation governing the armed forces and internal security forces allows for broad security force jurisdiction over criminal offences – including human rights violations – ensuring that investigations and trial of those accused of human rights violations takes place under a military justice system that violates international standards for fair trials. Further, it demonstrates how security forces operating in Jammu and Kashmir have exacerbated this situation by routinely failing to cooperate with criminal investigations, civilian courts and government-ordered enquiries, and subjecting those pursuing complaints to threats, intimidation and harassment.

METHODOLOGY

The findings of this report are based primarily on field research and documentation collected by an Amnesty International India team, during visits to multiple districts in Jammu and Kashmir in September and November 2013, and information provided by the central and state government authorities following applications for information filed under the Right to Information (RTI) Act, 2009 (Jammu and Kashmir State Act) and 2005 (Central Act).

Amnesty International India’s research team visited the two capitals of the state, Srinagar and Jammu, to meet with state officials, and the districts of Anantnag, Baramulla, Shopian, Pulwama, Budgam, Ganderbal, Bandipora and Kupwara. During the visit, researchers met with civil society groups such as the Association of the Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition for Civil Society (JKCCS), advocacy groups, lawyers, legislators, politicians, representatives of separatist groups, and representatives of the state government, including the Law Department, Home Department, the State Human Rights Commission, State Women’s Commission, and officials at the state police headquarters. Meetings were sought with central government officials in the Ministry of Home Affairs and Ministry of Defence in New Delhi, but official requests remained unanswered.

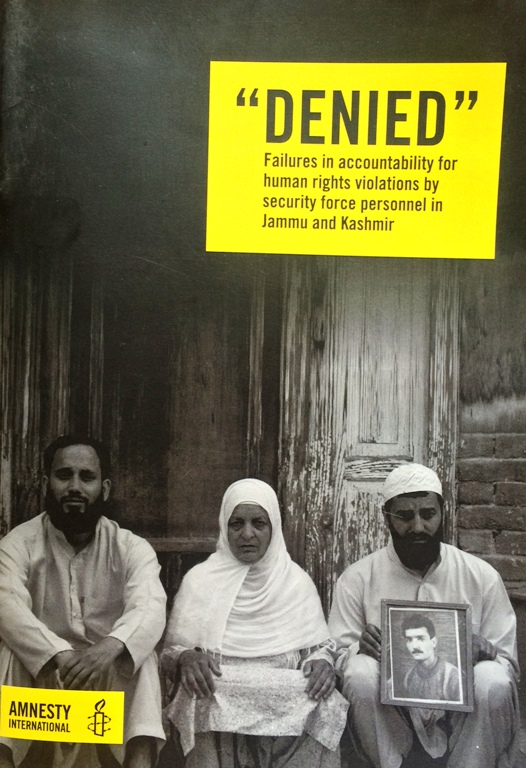

Researchers also met with 58 family members of victims of alleged human rights violations by security forces. These included both male and female members of each family when possible, including fathers, mothers, widows, brothers and sisters.

Interviews were conducted in Urdu, Kashmiri, Hindi and English, with the assistance of local interpreters wherever required. Where requested, the names of some persons interviewed during the course of research have been withheld for reasons of security and confidentiality.

Amnesty International India carried out specific research into cases included in official lists of cases in which sanction to prosecute was denied by the Ministry of Defence between 1990 and 2012. These lists were provided to Amnesty International India by the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition for Civil Society (JKCCS) which obtained them from the government after filing RTI applications in 2011 and 2012.

The International People’s Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in Jammu and Kashmir (IPTK), published a report – “Alleged Perpetrators: Stories of Impunity from Jammu and Kashmir” – in December 2012 that documented 214 cases of human rights violations based on police reports, families’ testimonies, and government records obtained through the RTI Act, and provided information such as court and police records to Amnesty International India on cases in which permission to prosecute was denied under the AFSPA.

Amnesty International India also filed RTI applications in June 2013 seeking updated information from the Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Home Affairs on cases in which the central and state governments have received requests from Jammu and Kashmir state police for sanction to prosecute. Amnesty International India sought information on the number of requests for sanction that have been denied or remain pending along with case numbers, charges filed against the accused, names of the accused, names of the victims, and details of each incident.

Amnesty International India received a reply from the Ministry of Defence on 18 August 2013 providing information on the number of requests for sanction received by the Ministry between 1990 and 2013. However, details of each case were withheld, citing sections of the RTI Act that exempt the government from providing information that would “prejudicially affect the sovereignty and integrity of India,” or “information which would endanger the life or physical safety of any person or identify the source of information or assistance given in confidence for law enforcement or security purposes.” This was despite the fact that detailed information of this sort had previously been provided to human rights activists as referred to above.

Amnesty International India received two notifications from the Ministry of Home Affairs dated 10 July 2013 and 5 August 2013 in response to its application for information, indicating that it had been forwarded to the appropriate authorities. However, no further information has been received. Amnesty International India also filed RTI applications seeking information from the seven internal security forces in India. The only forces to reply were the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) and Border Security Force (BSF). Both declined to provide the information requested.

RTI applications were also filed on behalf of Amnesty International India with the Jammu and Kashmir State Home Department by Muzaffar Bhat, an RTI activist based in Srinagar. Information requested included the number and details of requests for sanction for prosecution forwarded to the central Ministry of Home Affairs and Ministry of Defence between 1990 and 2013, and the number and details of cases requesting sanction from the state government to prosecute state police personnel for human rights violations under section 197 of the Jammu and Kashmir Code of Criminal Procedure (J&K CrPC). The state government provided the number of cases forwarded to the Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Home Affairs between 1990 and 2013, but withheld any details of these cases. The authorities did not respond to the application for the number of requests for sanction to prosecute under section 197 of the J&K CrPC in the same period.

This report also relies on data collected through daily news monitoring of issues related to past and ongoing human rights violations in the Jammu and Kashmir region; court and police records of families’ cases; and academic and other professional publications.

Amnesty International India would like to thank Parvez Imroz, Khurram Parvez and other staff of the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition for Civil Society, Parveena Ahangar and staff of the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons, and the lawyers of the Jammu and Kashmir High Court Bar Association, among many others who provided us with information, insight and logistical support.

Amnesty International India sent a copy of this report to authorities in the Ministry of Home Affairs on 27 April 2015, seeking a response to its findings by 14 May 2015. A copy was also sent to the Ministry of Defence on 6 May 2015, seeking a response by 20 May 2015.

On 22 May 2015, Amnesty International India wrote again to both Ministries, extending the time for response to 20 June 2015. Neither Ministry had responded at the time of publication.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The region of Kashmir has been a site of violence and conflict for decades. The AFSPA was introduced in parts of Jammu and Kashmir in 1990, following the beginning of an armed separatist movement for independence.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, there were grave human rights abuses committed by security forces as well as armed opposition groups. The 1990s witnessed a number of attacks by armed opposition groups on the Hindu minority Kashmiri Pandit community leading to hundreds of thousands fleeing the valley to live in displacement camps in Jammu and Delhi. Over the past decade, there has been a marked decrease in the level of violence. Regular local and national elections have taken place, notably in 2002, 2008 and 2014.

Popular protests against the state and security forces operating in the valley have been a feature of life in Jammu and Kashmir for many years. In recent years, particularly in parts of Srinagar and North Kashmir, protests have taken the form of marches with some young people throwing stones and security forces retaliating, at times with gunfire. More than 100 protestors, some of whom engaged in stone pelting, were shot dead by security forces in the summer of 2010. A further 3,500 persons were reportedly arrested and 120 detained under the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act (PSA). 23 In 2014, the Jammu and Kashmir State Home Department, in response to an RTI application, disclosed that 16,329 people had been detained in administrative detention under the PSA at various times since 1988.

In September 2010, the Government of India announced the appointment of a group of interlocutors to “begin the process of a sustained dialogue with all sections of the people of Jammu & Kashmir.” The group of interlocutors recommended that the government rehabilitate all victims of violence, facilitate the return of communities displaced from their homes, reduce “the intrusive presence of security forces”, and review the implementation of various Acts “meant to counter militancy”. However no formal action has been taken on the report.

In August 2011, the State Human Rights Commission (SHRC) in J&K stated that that it had found 2,730 unidentified bodies buried in unmarked graves in three districts of north Kashmir. The SHRC announced its intention to attempt to identify the bodies through DNA sampling.

However, the J&K state government informed the SHRC in August 2012 that conducting DNA profiling of the unmarked graves would not be possible because of inadequate resources, including lack of forensic laboratories and finances. No further action has since been taken.

In February 2013, unrest in the state was sparked by the secret execution of Mohammed Afzal Guru, after he was convicted of involvement in an attack on the Indian Parliament in New Delhi in 2001. Widespread protests in the Kashmir valley resulted in dozens of injuries to protesters, and several deaths due to firing by security forces.

Although less frequent than in the 1990s and early 2000s, deaths of members of the general population due to firing by security forces remain disturbingly regular. In 2013 alone, there were 12 deaths by security force firings in Jammu and Kashmir. Government-ordered enquiries into each of these deaths remain closed to public scrutiny, and no action appears to have been taken by the authorities to complete criminal investigations in a timely manner and prosecute suspects. In all 12 cases, media reports quoted police officials stating that none of the individuals killed had any links to militancy.

On 3 November 2014, two men were killed and two others seriously injured in Budgam district when Indian army personnel opened fire at their vehicle after it failed to stop at two army checkpoints. In an unusual move, the army authorities publicly admitted responsibility for the deaths of the two young men, Faisal Yusuf Bhat and Mehrajuddin Dar, and said that the killings were “a mistake”.

On 27 November, army authorities announced that nine personnel of the 53 Rashtriya Rifles would be formally prosecuted under military law for the killings. The father of one of the men continued to ask for the army personnel to be tried by a civilian court.

Suspected members of armed groups have continued to target members of the general public and local government officials, particularly around elections. National elections held in May 2014 saw a rise in the number of attacks against election officials, resulting in the deaths of a local village head and his son in Pulwama district, and another village leader in the same district on 21 April 2014.

The most recent state assembly elections were held between 25 November and 23 December 2014. A coalition government comprising the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Jammu and Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party took office on 1 March 2015, and released a ‘Common Minimum Programme’ setting out their joint agenda. The programme states: “While both parties have historically held a different view on the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) and the need for it in the State at present, as part of the agenda for governance of this alliance, the Coalition Government will examine the need for de-notifying ‘disturbed areas’. This, as a consequence, would enable the Union Government to take a final view on the continuation of AFSPA in these areas.”

Armed groups have been responsible for thousands of human rights abuses in Jammu and Kashmir. Victims of these abuses too have been unable to obtain justice. Amnesty International India consistently opposes all human rights abuses perpetrated by armed groups in Jammu and Kashmir, and calls for those responsible to be brought to justice.

LEGAL CONTEXT

LAWS COVERING SECURITY FORCE OPERATIONS IN JAMMU AND KASHMIR

The state of Jammu and Kashmir (with the exceptions of Leh and Ladakh districts) is classified as a “disturbed area” under section 3 of the Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act, 1990, according to the state government.

Section 4 of the AFSPA empowers officers (both commissioned and non-commissioned) in a “disturbed area” to “fire upon or otherwise use force, even to the causing of death” not only in cases of self-defence, but against any person contravening laws or orders “prohibiting the assembly of five or more persons.”

The classification of “disturbed area”, as described in greater detail in Chapter 5, has allowed the army and paramilitary forces to argue that they are on “active duty” at all times and that therefore all actions carried out in the state – including human rights violations – are carried out in the course of official duty, and are to be treated as service-related acts instead of criminal offences.

The Army Act, 1950, and similar legislation governing the internal security forces, contain provisions that prohibit security forces from investigating or trying “civil offences” such as murder or rape in the military justice system unless the act was committed “a) while on active service, or (b) at any place outside India, or (c) at a frontier post specified by the Central Government by notification in this behalf.” The classification of an area as “disturbed” has allowed the military and other security forces to claim that even serious human rights violations – extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearance, rape and torture – can only be tried by military courts, as the soldiers are considered to be on “active service” at all periods in such areas.

There are currently four main security forces operating in Jammu and Kashmir: the Army, the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF); the Border Security Force (BSF), and the state police.

In recent years, the army has largely withdrawn from towns in the state, including the capital Srinagar, and the town of Anantnag in south Kashmir among others, leaving the maintenance of law and order to the Central Reserve Police Force and the state police. Although the Government of India remains secretive about the size of troop deployment in Jammu and Kashmir, some experts not associated with the government estimate that 60,000 army personnel are stationed in the interior of the state to aid in counter-insurgency operations and the maintenance of law and order, while the rest of the army deployment guards the border and “Line of Control” with Pakistan. The army’s 60,000 troops are in addition to deployments of CRPF and BSF personnel, whose primary charge is to aid the state police in the maintenance of law and order.

Section 7 of the Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act enhances the protection provided to members of the security forces by requiring sanction or permission from the central government before members of the military or other security forces can be prosecuted in civilian courts. In the Army’s case, the concerned authority is the Ministry of Defence. For cases involving members of the internal security forces, permission has to be obtained from the Ministry of Home Affairs.

“Section 7 of the Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act 1990 Protection to persons acting in good faith under this Act. No prosecution, suit or other legal proceeding shall be instituted, except with the previous sanction of the Central Government, against any person in respect of anything done or purported to be done in exercise of the powers conferred by this Act.”

The classification of Jammu and Kashmir as a “disturbed area” has allowed for the broad interpretation of the phrase in Section 7: “anything done or purported to be done in the exercise of the powers conferred by this Act.” In several cases, victims’ families and their lawyers have argued that prosecuting civil offences such as murder or rape should not require sanction from the central government as such offences do not fall under the “exercise of the powers conferred” by the AFSPA (see Chapter 5). However, the army and internal security forces have successfully countered that all acts must be considered done in “good faith” since security force personnel are constantly on active duty and under threat in “disturbed areas”.

The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act – A history of challenges

In 1997, the constitutional validity of the AFSPA was challenged in the Supreme Court of India in the Naga People’s Movement of Human Rights vs. Union of India case.39 The Court, after hearing petitions challenging it, all filed in the 1980s and early 90s, upheld the constitutional validity of the AFSPA, ruling that the powers given to the army were not “arbitrary” or “unreasonable.”40 In doing so, however, the Court failed to consider India’s obligations under international law.

The Court further ruled that the declaration of an area as “disturbed” – a precondition for the application of the AFSPA – should be reviewed every six months. Concerning permission to prosecute, the Court ruled that the central government had to divulge reasons for denying sanction.

In 2005, a committee headed by B P Jeevan Reddy, a former Supreme Court judge, which was formed by the Supreme Court to review the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 after the alleged rape and murder of Thangjam Manorama Devi in Imphal, Manipur by security forces, said in its report that the law had become “a symbol of oppression, an object of hate and an instrument of discrimination and high-handedness.”

In 2012, a committee headed by J S Verma, a former Chief Justice of India, was established by the central government to review laws against sexual assault, following the gang-rape of a young woman in Delhi. The committee said that sexual violence against women by members of the armed forces or uniformed personnel should be brought under the purview of ordinary criminal law. To ensure this, the committee recommended the AFSPA be amended to remove the requirement of sanction to prosecute from the central government for prosecuting security force personnel for crimes involving violence against women.

In interviews with the media, J S Verma said that sexual violence could not in any way be associated with the performance of any official task, and therefore should not need permission to prosecute from the government.

Although new laws on violence against women were passed in April 2013, including the removal of the need for sanction to prosecute government officials for crimes involving violence against women, the recommended amendment to the AFSPA was ignored.

In January 2013, a commission headed by N Santosh Hegde, a former Supreme Court judge, was appointed by the Supreme Court in response to a public interest litigation seeking investigation into 1,528 cases of alleged extrajudicial executions committed in Manipur between 1978 and 2010. The Commission was established to determine whether six cases randomly chosen by the court were ‘encounter’ deaths – where security forces had fired in self-defence against members of armed groups – or extrajudicial executions. It was also mandated to evaluate the role of the security forces in Manipur.

The Commission, whose report was submitted to the Supreme Court in April 2013, concluded that all the cases it had investigated involved “fake encounters” (staged extrajudicial executions). It also found that the AFSPA was widely abused by security forces in Manipur. Notably, it reported that only one request for sanction to prosecute a member of the Assam Rifles under Section 7 of the Act had been made since 1998.

The Justice Hegde Commission proposed that all cases of “encounters” resulting in death should be immediately investigated and reviewed every three months by a committee. It also recommended the establishment of a special court to expedite cases of extrajudicial killings within the criminal justice system, and that all future requests for sanction for prosecution from the central government be decided within three months, failing which sanction would be deemed to be granted by default.

In November 2014, the Vice-President of India in a speech noted that serious human rights violations – including extrajudicial executions, torture, and enforced disappearance – were particularly acute in areas such as Jammu and Kashmir. He stated that “serious complaints are frequently made about the misuse of laws like the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act”, which “reflects poorly on the state and its agents.”

The AFSPA has also been subject recently to severe criticism by several independent United Nations human rights experts, including the Special Rapporteurs on violence against women; on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; and on the situation of human rights defenders.

Rashida Manjoo, the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, said in her official report to the UN Human Rights Council following her visit to India in April 2013 that the AFSPA “allows for the overriding of due process rights and nurtures a climate of impunity and a culture of both fear and resistance by citizens.” She called for the urgent repeal of the law.

Cristof Heyns, the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, visited India in March 2012. In his report to the UN Human Rights Council, he stated that “the powers granted under AFSPA are in reality broader than that allowable under a state of emergency as the right to life may effectively be suspended under the Act and the safeguards applicable in a state of emergency are absent.

“Moreover, the widespread deployment of the military creates an environment in which the exception becomes the rule, and the use of lethal force is seen as the primary response to conflict.” Calling for the repeal of the law, he said that “retaining a law such as AFSPA runs counter to the principles of democracy and human rights.”

Margaret Sekaggya, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, who visited India in January 2011, also called for the AFSPA to be repealed in her report, and said that she was deeply disturbed by the large number of cases of defenders who claimed to have been targeted by the police and security forces under laws like the AFSPA.

On 14 November 2014, the former Minister of Home Affairs for India, P. Chidambaram, spoke out against AFSPA in the wake of two deaths by army firing in Budgam district a few days before, stating in media reports that the Ministry of Home Affairs had begun the process of amending the AFSPA in 2010, but were “stoutly resisted” by the Army authorities and Ministry of Defence.

“The AFSPA is an obnoxious law that has no place in a modern, civilized country. It purports to incorporate the principle of immunity against prosecution without previous sanction. In reality, it allows the Armed Forces and Central Armed Police Forces (CAPF) to act with impunity,” Chidambaram said. In May 2015, he wrote, “If there is one action that can bring about a dramatic change of outlook from Jammu and Kashmir to Manipur, it is the repeal of AFSPA, and its replacement by a more humane law.”

Legal provisions which facilitate immunity from prosecution for security forces also exist in other special legislation in force in Jammu and Kashmir, which extend the powers of the state to use force or detain individuals. For example, Section 22 of the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act, 1978 provides a complete bar on criminal, civil or “any other legal proceedings…against any person for anything done or intended to be done in good faith in pursuance of the provisions of this Act.”

The requirement of sanction to prosecute police or security forces also exists in the ordinary criminal law. Section 197 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 provides that when a public servant is accused of any offence “alleged to have been committed by him while acting or purporting to act in the discharge of his official duty, no Court shall take cognizance of such offence except with the previous sanction” of the Central Government or relevant State Government (depending who the public servant is employed by at the time). Section 197(2) specifically provides for the granting of sanction by the Central Government in relation to members of the armed forces. There are instances where the Ministry of Home Affairs has denied sanction to prosecute internal security force personnel under section 197(2) of the CrPC.

A similar clause exists within the Jammu and Kashmir Code of Criminal Procedure, 1989. Section 197(1) of the Code protects Jammu and Kashmir state police personnel from prosecution in civilian courts unless sanction to prosecute is obtained from the Jammu and Kashmir Home Department.

Section 197(2), Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973

No Court shall take cognizance of any offence alleged to have been committed by any member of the Armed Forces of the Union while acting or purporting to act in the discharge of his official duty, except with the previous sanction of the Central Government.

CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS

Criminal investigations by Jammu and Kashmir state police into human rights violations, as with other offences, are typically initiated by the registration of a case (filing of a First Information Report (FIR)) against security force personnel by the victim or the family. Investigations are then conducted according to normal procedure under the Jammu and Kashmir Code of Criminal Procedure, 1989 (similar to the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 operative in the rest of India).

A number of concerns exist about the registration of complaints and investigation of human rights violations by police in Jammu and Kashmir which are explored in more detail in Chapter 7.

CRIMINAL PROSECUTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS

While legal provisions protect members of the security forces from prosecution, ordinary criminal law also fails to specifically criminalize crimes under international law such as torture and enforced disappearance.

As the law does not specifically recognize the offence of ‘enforced disappearance,’ allegations of enforced disappearances are registered, according to First Information Reports (FIR) on record with Amnesty International India, under section 364 of the Ranbir Penal Code (RPC) – “Kidnapping or abducting in order to murder,” or section 346 – “Wrongful confinement in secret,” or section 365 – “Kidnapping or abducting with intent secretly and wrongfully to confine person.” Each of these provisions carry a sentence of imprisonment of seven to ten years. Alleged extrajudicial executions, including deaths in custody, are typically registered under section 302 of the RPC – “murder”.

Similarly, torture is currently not punishable as a specific offence under the RPC (or the Indian Penal Code). Allegations of torture are instead registered as “voluntarily causing hurt,” or “voluntarily causing grievous hurt.” The definitions of grievous hurt are not in line with the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which India signed in 1997 but has yet to ratify. Proposals to further codify the crime of torture in a Prevention of Torture Bill, 2010, which lapsed in 2014, in any case fell short of the standard required under the Convention.

INDIA’S INTERNATIONAL OBLIGATIONS TO ENSURE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND REPARATION

Whenever serious human rights violations and abuses are committed (including torture, extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances, which are crimes under international law and violations against the international community as a whole) States are obligated to ensure truth, justice and full reparation to victims.

These measures are not discretionary. They form part of the duty of all States to provide an effective remedy to victims as recognized in international human rights law and standards, including Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, The Basic Principles and Guideline on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation or Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law, and Article 2(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 62 (ICCPR), to which India is a state party.

The right to truth

Ensuring the right to know the truth about past human rights abuses – for victims, family members as well as the general public – is recognized in international human rights law as part of a state’s obligation to investigate and provide remedy for violations of human rights.

States must take measures to:

establish the truth about human rights abuses, including their reasons, circumstances and conditions;

the progress and results of any investigation;

the identity of perpetrators, and in the event of death or enforced disappearance, the fate and whereabouts of the victims.

Truth is crucial in helping victims and their families understand what happened to them, counter misinformation, and highlight factors that led to abuses. It helps societies to understand why abuses were committed, so that they can prevent repetition.

The right to truth about human rights violations is recognized specifically in the International Convention on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, and increasingly recognized as integral to the rights to remedy and reparation under international law.

The Convention, which India signed in 2007 but is yet to ratify, recognizes the right to truth “regarding the circumstances of the enforced disappearance, the progress and results of the investigation and the fate of the disappeared person.”

The Human Rights Committee, a body of independent experts who monitor state compliance with the ICCPR, has stated that victims of all human rights violations must be allowed “… to find out the truth about those acts, to know who the perpetrators of such acts are and to obtain appropriate compensation.” The Updated Set of Principles for the promotion and protection of human rights through action to combat impunity, which was adopted by the UN Commission on human rights in 2005, states: “Every people has the inalienable right to know the truth about past events concerning the perpetration of heinous crimes and about the circumstances and reasons that led, through massive or systematic violations, to the perpetration of those crimes.” The right has also been recognized by the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances 66 and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

The UN Principles on Reparation establish that victims shall obtain satisfaction, “including verification of the facts and full and public disclosure of the truth.” The UN Human Rights Council and the UN General Assembly have also recognized in resolutions “the importance of respecting and ensuring the right to the truth so as to contribute to ending impunity and to promote and protect human rights.”

The right to truth entails the duty of the state to clarify and disclose the truth about gross human rights violations not only to victims and their relatives, but also to society as a whole. The right to truth cannot be separated from the right to justice.

The right to remedy

The right to a remedy is recognised in virtually all major international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which India is a state party.

The United Nations Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law clarify that remedies include:

equal and effective access to justice;

adequate, effective and prompt reparation for harm suffered and

access to relevant information concerning violations and reparation mechanisms.

International law requires that remedies not only be available in law, but accessible and effective in practice.

The right to reparation

Victims of human rights abuses, including crimes under international law, have a right to full and effective reparation. The right to reparation includes restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition. Reparation should seek to “as far as possible, wipe out all the consequences of the illegal act and re-establish the situation which would, in all probability, have existed if that act had not been committed.”

SANCTION

EVIDENCE OF THE USE OF SANCTION PROVISIONS

The requirement of sanction for prosecution is a colonial-era provision designed to protect then-largely British public servants from unnecessary and frivolous litigation. In practice it has led to impunity for serious human rights violations. While acknowledging that “civilians” have been killed by security forces, the Army has been known to publicly dismiss complaints of human rights violations and label the families and human rights activists who have brought them as “vested” or “motivated” by anti-national interests.

Authorities maintain that sanction provisions are necessary to prevent the filing of false cases against security force personnel by militant or terrorist groups. This refusal to acknowledge the legitimacy of complaints against the security forces is also reflected in the government’s blanket denial of sanction for members of the security forces to be prosecuted in civilian courts.

This report documents several individual cases of victims and their families denied justice through the sanction process. Information made available to Amnesty International India indicates that since 1990, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) has denied, or kept pending, all applications seeking sanction to prosecute army personnel for alleged human rights violations in civilian courts.

Sanction provisions violate India’s obligations under international law to prosecute and punish perpetrators of gross human rights violations, to combat impunity and uphold fair trial standards and maintain equality before the law.

REQUESTS FOR SANCTION MADE TO THE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE

Due to the lack of transparency around the process of seeking sanction, there is some confusion as to the exact number of cases in which the MoD has received applications seeking sanction. According to a Ministry of Defence response dated 18 April 2012 to an application filed under the Right to Information Act, 2005 by activists in J&K, the MoD had received 44 applications seeking sanction to prosecute army personnel for criminal offences committed in Jammu and Kashmir since 1990. The document indicated that sanction had been denied in 35 cases as of 3 April 2012 (it said that in one case, a court-martial had been conducted leading to conviction, dismissal from service and a sentence of rigorous imprisonment), while nine cases remained under consideration. Amnesty International India filed another application on 20 June 2013 requesting updated information on sanction applications to the MoD under the RTI Act. The MoD stated in its response that it had received 44 applications seeking sanction to prosecute, but declined to release the details of those cases, or the status of the applications.

Significant discrepancies exist between the information provided by the Ministry of Defence and data provided by the Jammu and Kashmir State Home Department in 2012 and 2013. In 2012, the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition for Civil Society obtained a list of 46 cases from the Jammu and Kashmir State Home Department through the RTI Act that had been sent to the Ministry of Defence since 1990 seeking permission to prosecute. The Ministry of Defence stated in an affidavit to the Jammu and Kashmir High Court in 2008 that it had not received 27 of the 46 cases that the Jammu and Kashmir State Home Department listed as sent to the Ministry. To date, the whereabouts and status of these 27 sanction applications are unknown.

To Amnesty International India’s knowledge, there have been no concerted efforts made to locate these cases or investigate these discrepancies. The MoD also reported that it had received 16 other cases that are not in the records of the Jammu and Kashmir State Government. In total, the MoD stated that it received 35 cases seeking sanction to prosecute between 1990 and 2007.

By Amnesty International India’s estimation, closer to 70 applications for sanction have been forwarded to the Ministry of Defence by the state government since 1990, some of which appear to have been lost between the Jammu and Kashmir State Home Department and the Ministry of Defence, and others that are not found in the Home Department’s records, but appear in the records of the Ministry of Defence.

Further, many details recorded in the applications forwarded for approval of sanction to the Ministry of Defence are wrong, including incorrect First Information Report numbers, names and dates of incidents, as well as incomplete information concerning the accused.

In 2013, the Jammu and Kashmir State Home Department stated in response to an RTI application filed by Amnesty International India that it had forwarded 39 cases for sanction to the Ministry of Defence since 1990, but declined to reveal the details of each case. Thus, cross-referencing the lists from 2012 and 2013 was not possible.

Justification for the denial of sanction

In a separate RTI response dated 10 January 2012, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) provided information on the reason for denial of sanction in 19 cases. In one case relating to a request to prosecute a member of the army for the alleged rape and sexual assault of two women in Anantnag district in 1997, the MoD stated, “there were a number of inconsistencies in the statements of witnesses. The allegation was lodged by the wife of a dreaded Hizbul Mujahideen militant. The lady was forced to lodge a false allegation by ANE‘s [anti-national elements] army.”

This is one example of the Ministry of Defence summarily dismissing a criminal investigation carried out by the police into a complaint of human rights violations in Jammu and Kashmir. This approach – utilising legal protections for members of the security forces to deny criminal prosecution in civilian courts and either dismissing the allegations outright or conducting its own “court of inquiry” – almost invariably results in the ultimate dismissal of the allegations and violates the right to justice and equality before the law.

REQUESTS FOR SANCTION MADE TO THE MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS

The Ministry of Home Affairs, which is vested with the authority to grant sanction for prosecution of members of internal security forces like the BSF and CRPF, has refused to disclose information about the number of requests it has received for sanction and the decisions made on those requests, despite multiple applications under the RTI Act in recent years. The Jammu and Kashmir State government told human rights activists in 2013 that it had forwarded 29 applications for sanction to prosecute members of the internal security forces to the Ministry of Home Affairs since 1990, but this figure is impossible to verify.

In response to RTI applications seeking this information from internal security forces directly, the Central Reserve Police Force and Border Security Force both claimed exemption under section 24(1) of the RTI Act, 2005 which provides that “nothing in this Act shall apply to the intelligence or security organizations… being organizations established by the Central Government… provided that the information pertaining to the allegations of corruption and human rights violations shall not be excluded under this sub-section”. They argued that “there appears to be no human rights violation/corruption. Further, there is no public interest to disclose such type of information or documents.”

REQUESTS FOR SANCTION MADE TO THE JAMMU AND KASHMIR STATE GOVERNMENT

The Jammu and Kashmir state government failed to respond to applications filed under the Jammu and Kashmir Right to Information Act, 2009 in June 2013 requesting details about the number of sanction applications it had received in relation to police personnel suspected of committing human rights violations. However, an affidavit filed by the Jammu and Kashmir Home Department in 2008 before the Jammu and Kashmir High Court stated that out of 458 cases seeking permission to prosecute army, internal security forces and Jammu and Kashmir state police for corruption and other offences from 1990 to 2007, the state government appeared to have granted permission to prosecute police personnel in up to 60 percent of applications received by them. However, the affidavit did not provide separate figures for human rights violations and corruption cases.

The additional law secretary for the Jammu and Kashmir Law Department told Amnesty International in February 2014 that his department receives between 20-25 cases every year in which the Jammu and Kashmir Home Department has granted sanction to prosecute police personnel for criminal offences, including human rights violations, under section 197(1) of the Jammu and Kashmir CrPC. However, he said that he was unaware of the total number of sanction requests that the Home Department receives, as the Law Department only receives applications that have been granted sanction. Apart from these, he said that the Law Department also receives an average of 25 – 30 cases annually under section 5 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, where sanction to prosecute has been granted.

THE SANCTION PROCESS

Neither the Armed Forces Special Powers Act nor the Code of Criminal Procedure prescribe a specific process for government authorities to follow to seek sanction for prosecution. Letters from Amnesty International India to the Ministry of Home Affairs and Ministry of Defence, as well as official requests for meetings to seek further information on the sanction process at the central level, went unanswered. However, officials at the Jammu and Kashmir State Human Rights Commission and in the Jammu and Kashmir Law Department described the process to Amnesty International India during interviews conducted in the state in 2013.

The sanction application process works slightly differently for members of the army and internal security forces, and the Jammu and Kashmir state police. When investigations into a criminal complaint against a member of the police or security forces are complete, the investigating authority, usually a member of the Jammu and Kashmir state police, is responsible for forwarding the established charges and any supplementary information to the Director General of Police, Jammu and Kashmir. The case is reviewed at the police headquarters by the Director Prosecution, and confirmed by the Director General of Police before being forwarded to the Jammu and Kashmir Home Department. The Director Prosecution has the prerogative to send the case back to the investigating officer if they feel the report is incomplete, or requires clarification.

If the accused is a member of the Army or internal security forces, the Jammu and Kashmir Home Department forwards the case to the central government for sanction (Ministry of Defence for the Army and Ministry of Home Affairs for the internal security forces). If the accused is a member of the Jammu and Kashmir State Police, the Jammu and Kashmir Home Department itself decides on whether sanction should be granted. According to information made available through the Right to Information Act, the MoD has taken anywhere from a few months to almost ten years to deny sanction to prosecute.

In an affidavit filed by the MoD in the Jammu and Kashmir High Court in 2008, the Joint Secretary for Defence replied to questions posed by the court regarding cases being processed for sanction, including the causes of delay in disposing of cases, and the estimated time the MoD would take to issue decisions in pending cases.

The affidavit provides some scant details on the sanction evaluation process: the case is received by the Integrated Service Headquarters – a separate department in the MoD comprised of staff from the Indian Army Headquarters and Ministry of Defence – for their “verification and comments.” The verification process is not detailed in the affidavit. After review by the Integrated Service Headquarters, consideration is given “on its merit whether the offence is proved and also whether it was committed while acting or purporting to act in the in discharge of official duties cast upon service personnel in the disturbed area”. The affidavit goes on to say that, “A decision is accordingly taken by the Ministry of Defence or the Ministry of Home Affairs whether or not to grant permission to prosecute in a civilian court.”

The affidavit also records that Courts of Inquiry – or military investigations – are held into each case received by the MoD. In the cases where reasons for denial of sanction to prosecute have been provided by the MoD, it is apparent that these Courts of Inquiry (concerns about which are discussed in Chapter 6 below) can contradict the findings of criminal investigations, leading to the denial of sanction and dismissal of the charges.

In its affidavit, the Ministry of Defence justified delays in evaluating sanction applications by pointing to the often long delay in criminal investigations by state police, in some cases of “up to 14-15 years for the police to conclude the investigation and seek permission from the central government to prosecute.” The Ministry of Defence stated that records, including police case diaries, forwarded in the sanction applications were often incomplete and/or illegible causing delay for officials attempting to fill incomplete details in a case with “proper application of mind.” Further, the MoD stated that by the time such applications for sanction were received by the central government, often the individuals and units involved in the alleged incidents were “moved/posted out long back making the process of identifying the individuals and records cumbersome and time consuming.”

Police investigations in Jammu and Kashmir have indeed been slow in many cases of alleged human rights violations by security force personnel, in some cases lasting more than a decade. This is often caused by the refusal of security forces to cooperate with criminal investigations, their non-compliance with court orders and refusal to produce accused personnel for questioning (documented in Chapter 7 below). Even in those cases in which the sanction application was received following police investigation within a year of the alleged violation, the MoD has failed to issue a prompt decision on sanction in the majority of cases: several cases have been under consideration for more than eight years without a decision.

LACK OF TRANSPARENCY

Not a single family interviewed by Amnesty International India for this report had been directly informed by the authorities of the status or outcome of a sanction request in relation to their case. As the procedure for deciding on whether sanction should be granted is not prescribed in law, there are no specific legal requirements to ensure that victims or their families are informed of the status or decision on sanction to prosecute in their cases.

The majority of victims’ family members interviewed by Amnesty International India in Jammu and Kashmir were unaware even of the requirement for sanction under the AFSPA and the ordinary criminal law, and whether their relative’s case had even been forwarded for sanction. Often, families mistakenly believed that the criminal case had been closed.

In 1999, the National Human Rights Commission issued a letter to all Directors General of Police in India on measures to help improve the relationship between the police and public. According to these guidelines, if an investigation of a case is not completed within three months, the complainant or victim is entitled to be informed in writing by the investigating officer of the reasons for the delay, and to be subsequently updated at three-month intervals. Among the reasons listed is the “non-receipt of prosecution sanction.”

The lack of transparency in the sanction process, and the authorities’ failure to inform families of the status or nature of the decision of the central government regarding sanction partly accounts for the low number of legal challenges to the denial of sanction to prosecute (see below). This is despite the fact that in 1997, when upholding the constitutionality of the AFSPA, the Supreme Court clarified that decisions on sanction were subject to judicial review.

CHALLENGES TO DECISIONS ON SANCTION

All of the 58 families interviewed by Amnesty International India said they had little or no faith that those responsible for human rights violations will be brought to justice, given the lack of accountability for security forces in Jammu and Kashmir over the past two decades. Due to the secrecy surrounding the sanction decision process, families are rarely, if ever, informed of sanction decisions issued by the authorities, and therefore are unable to challenge sanction denials. However, in a few cases, families have been able to challenge the denial of sanction. Their hope, they said, is that justice in their cases will help prevent others from becoming victims of human rights violations in the future.

Three families have directly challenged the decision of the MoD to deny sanction for prosecution in recent years: that of Manzoor Ahmad Mir, who was subjected to an enforced disappearance in 2003 and believed to have been extrajudicially executed; Ashiq Hussain Ganai, who was allegedly tortured to death in custody in 1993; and Javaid Ahmad Magray, who was allegedly extrajudicially executed in 2003.

In 2011, the family of Manzoor Ahmad Mir filed a petition in the Jammu and Kashmir High Court challenging the MoD’s decision to deny sanction to prosecute a Captain in the Army for Manzoor’s abduction and apparent murder in September 2003.88 The MoD’s decision was challenged on the grounds that it was arbitrary and a violation of Article 14 of the Indian Constitution (equality and equal protection before the law). To date, the Union of India has failed to file a response to the petition in the High Court. On 23 June 2015 the family’s lawyer informed Amnesty International India that the case had not been listed for hearing before the High Court for several months.

In 2003, the police filed charges of murder, kidnapping, evidence tampering and common intent against a Captain in the 23rd Rashtriya Rifles and two local informers, following an investigation into the disappearance of Manzoor Ahmad Mir. In a letter dated 9 May 2013, the Deputy Commissioner in Baramulla wrote to the Principal Secretary, Home Department, seeking permission to declare Manzoor Ahmad Mir “dead” and for benefits to be issued to his surviving family. He stated in the letter that: “The investigation indicates that the subject [Manzoor Ahmad Mir] was picked up by the above mentioned accused Army officer and his associates who killed him during interrogation and destroyed his dead body to save their skin for which section 201 of RPC (evidence tampering) was added. The report of the Inspector General of Police CID Jammu and Kashmir…reveals that on 7 September 2003, the accused Army officer…along with two civilian informers resident of Delina, Baramulla, searched his house, picked up the victim and since then his whereabouts are not known.”

The Army claimed protection for the accused Army Captain under Section 7 of the AFSPA stating that “no proceedings can take place against the accused till necessary prosecution sanction is obtained” from the Ministry of Defence. Based on this statement, the local judicial magistrate in Baramulla refused to take cognizance of the charges on 31 August 2005 until the Central Government granted sanction in the case. Manzoor Ahmad Mir’s family filed a petition challenging the order of the judicial magistrate before the Jammu and Kashmir High Court. On 21 April 2007, the High Court stated that the Magistrate “should not have acted on the application of the Army, as the Army was not a party before the court at all.”

The Ministry of Defence denied sanction in the case on 23 February 2009, justifying its decision on the grounds that “the allegation was motivated by vested interests to malign the image of security forces. Neither any operation was carried by any unit in the area nor was any person arrested as alleged.”

In an interview with Amnesty International India, Bashir Ahmad Mir, Manzoor Ahmad Mir’s brother said, “The whole system is corrupt. We are fighting for the guilty to be put behind bars, but it is impossible… The main aim is that the guilty should be punished so that no one else has to suffer this.”

In the case of Ashiq Hussain Ganai, who was allegedly tortured and killed by the army in 1993, the Ministry of Defence denied sanction to prosecute in 1997 without providing any reasons for their denial. On 14 May 1999, the family filed a writ petition before the Jammu and Kashmir High Court challenging the denial of sanction to prosecute the two army personnel identified by the police investigation. Multiple court adjournments followed, and the Jammu and Kashmir High Court granted further time to the central government to respond. The most recent court order available is dated 20 November 2006, in which the High Court granted further time to the Union of India to submit a response to the challenge. No further action is known to have been taken.

CHALLENGES TO THE APPLICABILITY OF SANCTION PROVISIONS

Section 7 of the AFSPA or similar provisions that require sanction for prosecution should not be allowed to be invoked by the security forces in cases where human rights violations have been alleged. Sanction provisions, under law, only apply to acts committed during the course of official duties, or for “anything done or purported to be done in exercise of the powers conferred” by the AFSPA.”96 Murder, rape and other offences amounting to human rights violations cannot be considered under any circumstances as having been carried out during the course of official duty. In a number of cases, families and lawyers have sought to make such arguments before authorities and courts. Even investigative agencies such as the Central Bureau of Investigation have similarly argued that the intentional killing of civilians cannot be protected by immunity provisions in existing legislation as any such action could not be considered an official act.97 Trial courts in Jammu and Kashmir have made similar observations.

Two high-profile cases invoking this argument have reached the Supreme Court of India. A counsel for the Union of India, and former counsel for the Army in Jammu and Kashmir, speaking under condition of anonymity said: “There are just a few of these cases that have gone to the Supreme Court, but if you went to each of the [lower courts] in Jammu and Kashmir, you would find dozens, if not hundreds, of records in which the security forces just take the cases back into their own courts, and the families don’t have the resources to fight it.”

The Pathribal Case

“The night they took my father, I was sleeping upstairs. I remember hearing the army personnel barge in and ask for someone to show them the way through the fields. My father was not very well, so I ran downstairs and offered to show them. But the army officer said: ‘No, don’t take him, the children are too young. Take the father.” Abdul Rasheed Khan, son of Juma Khan, who was allegedly killed in an extrajudicial execution in 2000.”

Abdul Rasheed Khan’s father Juma Khan was one of five alleged “militants” who were allegedly executed extrajudicially near Pathribal village on 25 March 2000 by personnel of the 7 Rashtriya Rifles in a staged “encounter”, and whose bodies were subsequently buried in a forest nearby.

The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) – India’s premier investigating agency – which initially investigated the killings (including identifying the buried bodies through forensic tests and subsequently establishing that the individuals killed were not associated with militancy) said the incident was ‘cold-blooded murder’. In 2006 they charged five soldiers with offences including criminal conspiracy, murder and kidnapping.

Utilising Section 7 of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, the army blocked prosecution, arguing that the case required government sanction under the AFSPA. The Supreme Court upheld the requirement that no criminal proceeding could be initiated against army personnel without the central government’s permission and gave the army the option of handing over the accused army personnel to the civilian courts, or trying them by court-martial. The Court clearly stated, “in case the option is made to try the case by a court-martial, the said proceedings would commence immediately and would be concluded strictly in accordance with law expeditiously.”

The army initially appeared reluctant to try the case in a military court. In January 2012, according to press reports, the Additional Solicitor General, P.P. Malhotra, told the Supreme Court that the Army was not interested in bringing the officers to a court martial under the Army Act. “We cannot take over the case,” Mr. Malhotra said. “The Armed Forces are bound to protect their men.”101 One of the Supreme Court justices on the two-judge bench, Swatanter Kumar, told Malhotra, “You [the Army] don’t want to take over the case and initiate court martial proceedings against them. You don’t allow the criminal justice system to go ahead.” Justice Chauhan, the second member of the two-judge bench, also expressed concern: “The victims cannot be remedy-less. No person can be harassed. No jawaan (soldier) should exceed limits. You cannot interpret and misinterpret the law and expect citizens to wait.”

The army ultimately chose to handle the case within the military justice system and announced that it would begin proceedings on 20 September 2012. On 24 January 2014, nearly 18 months after the Supreme Court order, army authorities dismissed the charges against the five accused personnel citing “lack of evidence.” Abdul Rasheed Khan told Amnesty International India that none of the families were informed directly by the army of the outcome of the military proceedings, but only learnt of the development on 24 January 2014 when the army’s dismissal was reported by the media.

According to the closure report filed before the Chief Judicial Magistrate in Srinagar, the army never conducted a trial. Instead, the army dismissed the case under Rule 24 of the Army Rules, 1954 after a pre-trial procedure called the summary of evidence (see below for description of this process). There is no apparent possibility for the victims’ families to appeal or review the decision reached through the military justice system. The CBI report is not available in the public domain. Despite several attempts–including talking to the lead investigator on the case for the CBI and the defence counsel–Amnesty International India was unable to obtain a copy of the report.

THE ZAHID FAROOQ SHEIKH CASE

“We will fight as long as we can. As long as the courts allow us to appeal, we will appeal over and over again, even if it takes another decade.” Farooq Sheikh, father of 16-year-old Zahid Farooq Sheikh, who was killed by security forces in 2010.

Just a year after the Supreme Court granted the army permission to try its personnel by a court martial in the Pathribal case, in April 2013, the Supreme Court again granted security forces the option to try their own personnel: this time the Border Security Force. 16-year-old Zahid Farooq Sheikh was killed in 2010 by the Border Security Force personnel as he was walking home from playing cricket with friends in Srinagar.

Unlike many past cases of alleged human rights violations, the state police investigation into Zahid’s killing was conducted swiftly, and within a few weeks of the incident, the police filed charges of murder against two BSF personnel. The BSF did not deny that their soldiers were responsible for Zahid’s death, and began conducting security force court proceedings against the accused after the conclusion of the police investigations, arguing that because their personnel are always considered on “active duty” in a state designated as “disturbed,” they were empowered to try their personnel in a military court.

Zahid’s father, Farooq Sheikh and his family petitioned to have the case tried in a civilian court as they were not convinced they would get justice from the security forces. “We are not told anything when they conduct a trial. We don’t have access to any information. How will we know that the guilty are even punished? The only way we can be sure is to have the trial in the civil court,” said Farooq Sheikh.

In March 2013 Farooq Sheikh was called to testify before the BSF Security Force Court. Farooq says the BSF summoned him several times through the local police, but he was reluctant to attend the proceedings as they were held at the BSF camp at Panthachowk in Srinagar, which only military personnel are usually allowed to enter. He said he felt nervous about entering the BSF premises, and feared intimidation or harassment.

Farooq said that he and another witness, Mushtaq Wani, who was with Zahid when he was killed, went to testify before the Security Force Court, also in March 2013. The BSF had appointed a lawyer for them, who Farooq says was from Jammu. Farooq said, “They repeatedly tried to discredit Mushtaq. They repeatedly projected the incident as if there was stone-pelting at the time. But the police have made official reports that everything was normal at that time. No stone-pelting was going on…The cross-examination was done by a soldier who questioned Mushtaq and kept accusing him of being a militant, asking him about his activities and whereabouts.”

Farooq told Amnesty International India that he did not trust the BSF court proceedings. At the hearing, Farooq says that there were 14 other witnesses produced by the local police and witnesses from the BSF side. When he went to testify, he says, a senior officer of the unit fell at his feet and said, “Please forgive me, we have made a mistake.” Farooq replied, “How can I forgive you. You have killed an innocent boy.”

Zahid’s cousin, Nasir Sheikh added: “They [the BSF] will complete the investigation and trial, they have just one or two more witnesses to depose before the court, and then most probably the accused will be transferred to another place, and we will never know what comes of the case. Just like in the Pathribal case, the BSF are saying that there were no eyewitnesses to the incident so they cannot charge the accused with murder.”

The BSF court proceedings were yet to conclude at the time of writing. Farooq Sheikh said he has not been contacted by BSF authorities since he attended the hearing at Panthachowk in 2013.

Farooq Sheikh and his lawyer, Nazir Ronga, continue to fight for the case to be tried in the civilian court: “The fact that the BSF are fighting so hard to bring the case back into the military court makes me suspicious. What are they trying to hide?” says his lawyer. Having had their appeal to the Supreme Court dismissed once, they applied to the Jammu and Kashmir courts again on the grounds that the Border Security Forces did not try their personnel within the time directed by the Supreme Court. However, the Sessions court in Srinagardirected the family to approach the Supreme Court again to seek re-evaluation of its decision in June 2014.

THE MACHIL CASE

On 28 April 2010, Shazad Ahmad Khan, 27; Riyaz Ahmad Lone, 20; and Mohammad Shafi Lone, 19, travelled to Machil, an area close to the Pakistani border about three hours from their homes, on the promise of work from a man named Bashir Ahmad Lone who lived in their village. They never came back.

The next morning, all three families approached Bashir Ahmad Lone to ask about their sons’ whereabouts. He denied he had taken them to Machil the previous day. The next day, there was a report in the media that said that the army had killed three infiltrators in a fake encounter.

The families began to suspect that the militants reported in the newspaper were in fact their sons. They approached Baramulla police station and registered a case against Bashir Ahmad Lone. The police began investigations into the case and filed charges of murder and conspiracy to commit murder against 11 persons: two villagers, and nine army personnel (including three officers) which they submitted to the Chief Judicial Magistrate in Sopore, Baramulla District, on 15 July 2010.