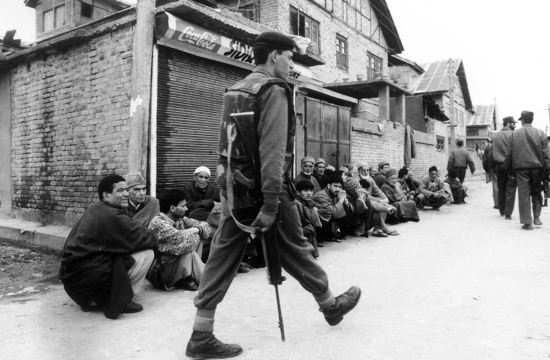

A series of crackdowns starting from old Baramulla coupled with valley-wide whip on dissenters stirred up the haunting memories of those harrowing days in Kashmir when such exercises would force civilian population tremble in fear, reports Bilal Handoo

When Baramulla’s old town woke up to queer noises around 4am on October 17, many residents thought it as a nocturnal raid. By daybreak when mosque speakers started blaring out the alarming announcement, everyone’s sleep ended. The township was put under crackdown, the cordon-and-search operation, that has haunted Kashmiris for decades.

Javaid Ahmad, an early riser, saw men being assembled in an open yard for the parade. “Some cops had conveyed to the elderly civilians that they have come to hunt down Jaish militants supposedly hiding in the town,” Javaid says. To evade possible arrests, some boys had already fled to woods.

After men were ordered out of houses by a joint posse of soldiers, cops and paramilitary men, door-to-door searches started. Around 3pm that day, the crackdown ended with around 35 “miscreant” detentions. Last time, Javaid says, the townspeople had witnessed such crackdown during nineties. “We relived that nightmare.”

The nightmare returned a few days later when a local fruit seller accused of feeding dinner to militants was roughed up in another crackdown, Javaid, a resident of Shah Hamadan Colony, says. Boys were forced to erase anti-India graffiti from walls. “A local was asked to chant: ‘Kashmir Bharat ka atoot ang hai’,” he says. “Before forces would draw back, Go India Go graffiti had become We Indian Come Back.”

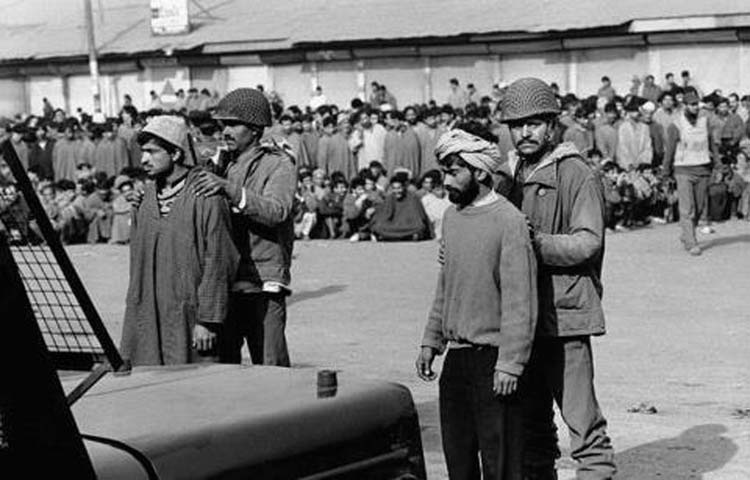

Baramulla operation was termed part of the biggest civilian crackdown in two decades that sent 446 people behind bars within a week across valley. Since July 8, when Burhan was killed, police created a record by detaining around 9000 people, around 500 of them booked under Public Safety Act.

These crackdowns are normally nocturnal affairs. In Old Barzulla, residents still shudder to recall how their homes were stormed by cops carrying sticks, and axes.

In one such raid at Khrew this past summer, a school teacher was beaten to death. Though the intensity of raids has gone slightly down in last one fortnight, scores of youth have gone into hiding.

Some of these raids became challenging for forces as communities at times rose up—like the one in Anchar locality where around 100 people sustained injuries including a senior cop in fierce clashes that erupted after a raid. These crackdowns ended up invigorating Kashmir’s bygone nightmare.

When Kashmir’s senior lensman Amin War went to cover a crackdown in Batamaloo during early nineties, he was detained by army and kept with identified men. “I was stunned,” War recalls, “when I found my neighbour missing for over a month among the detained men there.” The man told him that he was turned into a cat, an informer. Before parting, the neighbour sent a word for his family: “Please tell them, I am alive.”

Next time when War went to cover crackdown in north Kashmir’s Hatmulla, he was detained by the same army that had invited him from Srinagar for coverage. “Those were mad times when nothing made sense,” War, now serving Tribune, smiles over reminiscence. “Besides beating me black and blue, socks were shoved into my mouth, making me vomit my guts out.”

During one such exercise on November 2, 1995, a government official was detained in Srinagar, taken inside BSF camp where he saw five tortured civilians with pherans pulled around their heads.

Inside a BSF commandant asked him: “Tell me where the militants are?” Showkat Mir, the government official, had a curt reply: “I don’t know.”

“We will render you impotent if you do not cooperate,” the officer said. Shortly, a stripped Mir was given electric shocks to his genitals.

A day after, he was taken to Papa II—now Fairview (CM residence)—where he met Badshah Khan, JKLF’s district commander from Kupwara. “Khan’s back was burnt with kerosene oil,” he says. “I simply witnessed humanity being put at shame inside that torture centre.” To his good luck though, Mir was shortly released. But he walked out as a changed man. “I was rendered impotent!”

A Srinagar-based scribe visiting his parents in Shopian in summer 1994 returned highly disturbed. Sudden crackdown in the town had turned him into a captive audience of a commandant.

“What left me seething in rage was the officer’s outrageous remark: ‘These militants for whom you have a soft corner often end up outraging your sisters’ and daughters’ modesty.’ It took me a while to recover from the shock.”

Certain crackdowns would turn nasty as was one in Dalgate where four youth were detained in a crackdown in 1993 and within half an hour, their corpses were thrown around.

“Dozens of such killings occur every month in Kashmir,” US State Department noted in its 1995 annual report. “Detainees have also disappeared in custody after being detained by forces during crackdown.”

There are also instances when people were taken out of homes like animals and left to fend for themselves in chill and scorching sun. However, Abdul Rashid, a health official at SKIMS tells a different story.

Before mid-1995, BSF used to patrol SKIMS hospital, looking for militants. They would conduct crackdowns inside the hospital, directing staff to line up and be searched, Rashid says.

Then Ikwan-ul Muslimoon—a pro-government militia—would patrol SKIMS and Bone and Joint Hospital under the command of Mohammad Ramzan, an ex-JKLF militant-turned-renegade. They would carry out joint crackdowns with forces at will. “Ramzan would be seen at the hospital accompanied by other gunmen and by army soldiers wearing Rashtriya Rifles uniforms,” Rashid says. “He had told hospital staff that he ‘wanted to bring discipline to the Institute.’ ”

In November 1995, Ramzan’s mercenaries dragged a surgeon out of his office and kicked and punched him, Rashid says. “Armed with automatic weapons, they would enter the hospital regularly in groups of twelve, impose crackdown and take suspects away to ‘camps.’ ” One such camp was located at an army base 3km away at Bachapora.

By then, crackdown had become a pan-Kashmir phenomenon, leaving behind a trail of trauma, like it did in a frosty day of January 20, 1995.

That day, Batamaloo was draped in a thick blanket of snow. Soldiers of 2nd Grenades suddenly showed up and conducted crackdown. They soon came under heavy firing, recalls Abdul Aziz, a resident of Batamaloo. “They used a local guide as human shield,” he says. Men were assembled in a local graveyard where they were shivering in cold.

Inside the cemetery, Aziz heard cries of a young boy coming from a nearby Government Middle School Lachmanpara—commonly used as an interrogation centre during crackdowns. “Early that morning, a boy was detained and taken inside the school,” he says.

Shortly, the soldiers flanked by an informer came surveying the men inside the graveyard and pointed at a local trader, Aziz says. “The trader was dubbed as Afghani mujahid before being taken inside that school.”

Crackdown ended at 9:00pm, but suspense ended when a police officer told the locals that three civilians were killed earlier that day in “crossfire” at Batamaloo. Next morning, the three bullet-riddled bodies were found in truck at Shergari Police Station. “Among the slain were the local boy and the local trader,” Aziz says.

Equally dreadful is an account of eighteen-year-old deaf and dumb boy of Bulbulankar Nawakadal. Around 10:00am on December 21, 1995, Ghulam Ahmad Bhat along with his mother and neighbours were out to see a procession held to mourn the killing of Khurshid Bhat, then Al Jihad outfit chief.

“Suddenly a crackdown was imposed by 7th BSF Battalion under Commander ‘Peter’ Sharma,” says Syed Waseem, a local banker. “The boy ran along a long, narrow lane after seeing BSF.” He stopped to show the soldiers that he was deaf and dumb, the banker says. “One among the three soldiers chasing him fired a machine gun burst, killing him inside the lane. His mother who ran to protect him later told us how a soldier kicked her son’s body to make sure he was dead. ‘Shortly,’ the mother said, ‘three BSF soldiers came to put a pistol on my son’s chest and bullets in his pheran pocket.’ ”

The crackdown was lifted at 2:00pm that day. Police arrived, Waseem says, and screamed at the BSF, “Why did you kill him?! He wasn’t a militant!” Next morning, the banker says, Commander ‘Peter’ sent two local shopkeepers with an offer of Rs 2 lac as “blood money”, in lieu of not filing the case, a proposal the mother rejected.

Similar mayhem unfolded in Chanapora on December 27, 1992 when people out on crackdown ran for a cover after fireworks started. Three men after giving safe passage to people climbed over a fence and ran through an apple orchard for safety. A BSF man who gate-crashed the orchard followed them with his LMG. He fired, and two were killed on spot. One managed to flee and took shelter in nearby house before another announcement took him back to street. “Near dusk,” says Showkat Ahmad, a third survivor and now a senior JKLF member, “I was paraded before BSF jeeps. A cat in fifth jeep beeped and I was instantly bundled into the vehicle and taken to Chanapora CRPF camp where I was roughly tortured.” The crackdown ended 48 hours later.

Crackdowns created many near death experiences. In a mid-nineties crackdown, a mother jumped from three-storey residence to divert BSF attention, who had come to hunt for her militant son. “Her son survived,” says Imran Sheikh, a local in Khanyar, “but his brothers in arm—Nik Mir and Nik Tin—were killed.” And the mother never walked the same again.

But the most covert part of those crackdowns was the unspoken shaming of Kashmiri women inside homes.

Islamabad’s Ruksana, a mother of two, is married to Srinagar-based goldsmith for 11 years now. She still remembers how females had to accompany the searching squad inside homes after males would be taken out on parade during nineties.

“At times it was humiliating when soldiers would force you to open your cupboard and ran their hands through yours inner wears and then make you to watch the act,” Ruksana falters to speak. In Srinagar, a similar humiliation was experienced by a government teacher.

In mid-nineties, when forces asked Sibtain to accompany them for searching, she quivered in fear. “After making mess of everything including tearing down the roof,” she says, “one BSF men caught hold of my inner wear and visibly derived sadistic pleasure out of it.”

Such was its impact on the tender mindset of then teenage girl that she required psychiatric help.